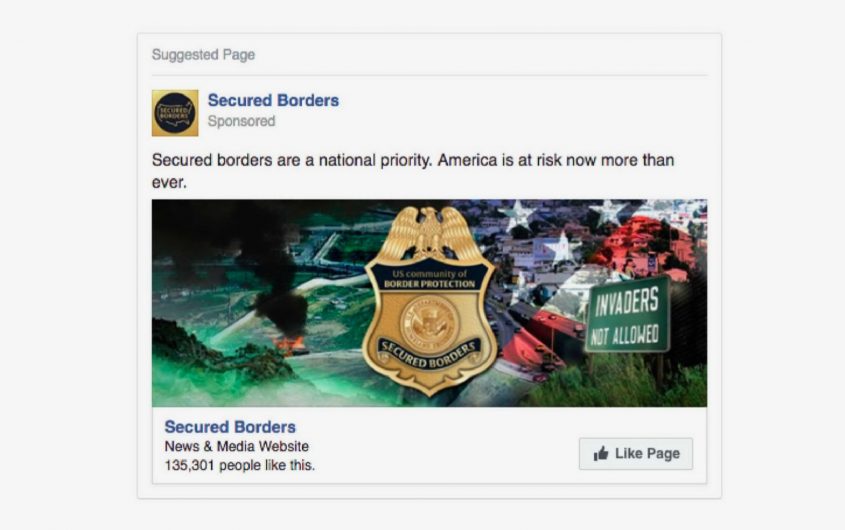

Sample ad via U.S. House of Representatives Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence

Election Meddlers and Transatlantic Remedies

Sarah Lohmann

Dr. Sarah Lohmann is Non-Resident Fellow with the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies at Johns Hopkins University. Dr. Lohmann is an Acting Assistant Professor in the Henry M. Jackson School for International Studies and a Visiting Professor at the U.S. Army War College. Her current teaching and research focus is on cyber and energy security and NATO policy, and she is currently a co-lead for a NATO project on “Energy Security in an Era of Hybrid Warfare”. She joins the Jackson School from UW’s Communications Leadership faculty, where she teaches on emerging technology, big data and disinformation. Previously, she served as the Senior Cyber Fellow with the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies at Johns Hopkins University, where she managed projects which aimed to increase agreement between Germany and the United States on improving cybersecurity and creating cybernorms.

Starting in 2010, Dr. Lohmann served as a university instructor at the Universität der Bundeswehr in Munich, where she taught cybersecurity policy, international human rights, and political science. She achieved her doctorate in political science there in 2013, when she became a senior researcher working for the political science department.

Prior to her tenure at the Universität der Bundeswehr, Dr. Lohmann was a press spokeswoman for the U.S. Department of State for human rights as well as for the Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs (MEPI). Before her government service, she was a journalist and Fulbright scholar. She has been published in multiple books, including a handbook on digital transformation, Redesigning Organizations: Concepts for the Connected Society (Springer, 2020), and has written over a thousand articles in international press outlets.

People whose Facebook profile yields matches for the key words Jesus, Christianity, Bible, Fox News Channel, very conservative, Rush Limbaugh, Mike Pence, Breitbart, and Mike Huckabee were targeted with digital propaganda by Russian operatives, according to Facebook ad records obtained by the U.S. House of Representatives Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence and posted on its website.[1]

These advertisements, placed under the rubric “Secured Borders News and Media Website,” were to play on controversial issues to the American public, in this case, the discussion around immigration, with messages such as: “Secured borders are a national priority. America is at risk now more than ever.” The Russians paid 2094.74 Rubles (about $33) for that ad last year, long after the elections were over.[2]

Voters of other religions and political persuasions were not off the hook. Ads placed eighteen months before the election through last year targeted everyone from “people who like” Bernie Sanders; Second Amendment rights; Martin Luther King, Jr; Hillary Clinton; Black Lives Matter; and Muslims living in the United States. The messages were to inflame tensions around race, religion, and cultural pride.

The Russian effort was extensive, sophisticated and ordered by President Putin himself.

– Senator Mark Warner

The April findings of the House Intelligence Committee on Russian interference in U.S. elections provided evidence enough for discomfort about the vulnerability of U.S. voters for information operation campaigns. Even more unsettling is that according to statements made by Senators Burr and Warner on May 16, following the release of the Senate Intelligence Committee report on May 8, the American election system remains at risk. Senator Warner of Virginia said that “The Russian effort was extensive, sophisticated and ordered by President Putin himself.”[3] The report found that election infrastructure remains vulnerable as voting systems are outdated and can be accessed through the Internet.[4]

The Election Meddling Problem

The Russian interference has a dual strategy: cyber espionage on U.S. voting infrastructure and its system weaknesses, and a digital propaganda campaign. This information operation used targeted ads created by the Internet Research Agency (IRA), a Russian troll farm that also used fake U.S. personas to spread propaganda on divisive issues. The ads reached 11.4 million Americans on Facebook alone. Worse, at least 126 million Americans were exposed to the content created by 470 IRA Facebook pages.[5]

“Cyber actors affiliated with the Russian government” targeted eighteen state election systems, “conducted malicious access attempts” in six states, and in a handful of states, gained access to the restricted portions of election infrastructure, with the ability to delete voter registration data, according to the Senate report.[6] A spike in reports of hundreds of thousands of voters being deleted from the rolls in key swing states such as Ohio, Indiana, North Carolina, and Florida, starting in 2015 should be further investigated. The Senate Committee warned: “The Committee notes that a small number of districts in key states can have a significant impact in a national election.”[7]

Across the Atlantic, Europe has concerns about meddling ahead of the European Parliament elections next year, after information campaigns targeted the French and German elections and the Catalonian independence referendum last year. Stratcom, an EU foreign service counter-propaganda unit, documented more than 3,500 cases of pro-Kremlin disinformation in the European media in the last two years.[8]

Stratcom documented more than 3,500 cases of pro-Kremlin disinformation in the European media in the last two years.

During the German elections, Russia promoted the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) in its state-controlled networks, and planted disinformation about the refugee-friendly Angela Merkel. One such campaign, known as the “Lisa affair,” widely covered a false story about a girl who was supposedly raped by refugees. The misleading coverage of the German election season helped prompt Merkel to travel to visit Putin in Sochi to warn about election meddling.[9]

The Russian botnet IRA was not interested in meddling in just the U.S. election. Before the French elections, 30,000 fake IRA accounts were detected and destroyed by Facebook.[10] Russian-language faceless accounts thought to be botnets were also notably used the day before the German election to bolster the turn out for the AfD through fake news stories spread through fake accounts that claimed that AfD voters could be disenfranchised of their voting rights.[11]

Legislative Solutions

To deal with their digital propaganda problem, Germany passed the Network Enforcement Act (Netzwerkdurchsetzungsgesetz, abbreviated NetzDG) last year. It went into effect on October 1, 2017. The law requires social media platforms such as Facebook to delete propaganda, hate speech, and fake news within 24 hours of notification of a complaint, or face fines of €50 million. Individuals can face fines of up to €5 million for posting hate speech or fake news. Facebook has hired 4,500 employees just to screen and delete hate speech, and announced this month that it is hiring 3,000 more.[12]

The law has been controversial not just because it puts the main burden on the social media platforms, which are just the conduit, rather than the creator, of propaganda or hate speech. NetzDG is also accused of limiting freedom of expression, as it would have social media platforms delete anything from distribution of propaganda, to insults, to depictions of violence, to incitement of crime, to pictures of intimacy, to hate speech against groups of people.[13]

Both Twitter and Facebook have come out in support of the U.S. draft equivalent of the NetzDG, called the Honest Ads Act. While ads in media such as television, radio, and newspapers have long been kept accountable by electioneering communication laws, the Senate legislation would allow paid internet and digital ads to be regulated as well.

It would also require the platforms to make “reasonable efforts” to ensure that foreign entities are not buying the ads to influence the American electorate. What these reasonable efforts would consist of is not further defined in the draft law. A person or group who spends more than $500 must document their target audience, views, dates, and times of publication and contact information. That means that disguised messaging, such as the Secured Borders ad mentioned at the beginning of this article purchased for just $33, would fly under the radar unless the affiliated group purchases many ads.[14]

The bill remains stuck in the House, in need of an upgrade that would bring more specific language on accountability for foreign actors to bear.

Transatlantic Cooperation Remedies?

In answer to the challenge of foreign interference in U.S. elections, the Senate report provided several recommendations. First, the “State Department and Defense Department should engage allies and partners to establish new international cyber norms.”[15] While both departments have remained active in engaging partners over the last eighteen months since the election, a few changes would help with this engagement.

First, although the State Department has long taken the lead on discussing cyber norms with allies, allies have not had a cyberdiplomat with a direct line to the president to coordinate with since former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson eliminated the coordinator position last August. For allies looking for a phone number to call, the current state of affairs is confusing, to say the least. With the additional deletion of White House Cybersecurity Coordinator Rob Joyce’s position last week, coordination across both the State Department and the many cabinet agencies handling cybersecurity concerns remains a challenge. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has promised to make cybersecurity a priority.[16] Reinstalling a top cyber diplomat should be at the top of the to-do list.

Second, the report calls for improved information sharing with allies on threats. While the United Nations General Assembly group of experts, which included the United States and Germany, could agree to basic concepts of international law being applied to cyberspace, in 2017 there was disagreement about the creation of an attribution council. A precondition for forming the council was that sensitive information about weaknesses and perpetrators would need to be exchanged between intelligence agencies and Computer Emergency Response Teams, a step certain agencies weren’t willing to take.[17]

How to improve Confidence Building Measures (CBMs), which reduce fear of attacks, in alliances where information sharing only takes place in fits and starts, has become a key challenge.

How to improve Confidence Building Measures (CBMs), which reduce fear of attacks, in alliances where information sharing only takes place in fits and starts, has become a key challenge. On the operative and technical level, outside of the political decisions intelligence agencies are forced to make, unit to unit and military branch to branch information sharing could forge a way forward for information sharing.

Third, the Committee’s proposal for the intelligence community to “put a high priority on attributing cyber attacks both quickly and accurately”[18] is easier said than done. With states often using proxies, and actors funneling their attacks through innocent third-party systems, attribution is often difficult to ascertain without a shadow of a doubt. Multiple IP addresses can be used, and actors connected with the state may not always explicitly be paid or ordered to make attacks on behalf of the state.[19] Use of standardized attribution methods, and relying on a variety of actors (whose motivation cannot be profit) to identify the perpetrators, is key to ensuring that attribution can occur both quickly and accurately.

On the domestic side, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) was called upon to “create clear channels of communication between the Federal government” and officials at the state and local level.[20] While DHS has been spearheading the efforts to help state election officials improve their voting systems, with the White House coordinator position eliminated, this could be a challenge. Grassroots efforts at the state level to prioritize spending to protect and upgrade voting systems, educate election monitors, and inform state leadership will have to be prioritized in the meantime.

The U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence report underscored the urgency of preparedness for future election meddling. As the 2018 mid-terms near, local and national cybersecurity plans need to be in place for both voter system infrastructure, and to create legal accountability mechanisms so that foreign interference is no longer allowed to continue. Cooperation with allies on cyber norms, and information sharing on attribution will need to be intensified for the national security of both Germany and the United States. Holding foreign meddlers accountable, in a coordinated and unified fashion, will be vital to protect both cybersecurity at home now, and the bilateral relationship in the future.

[1] “Social Media Advertisement,” U.S. House of Representatives Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, Democrats, https://democrats-intelligence.house.gov/facebook-ads/social-media-advertisements.htm

[2] See ad 1253 – 2017, Quarter 3, PDF file 3115 – on the U.S. House of Representatives Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence website.

[3] “Senate Intel Completes Review of Intelligence Community Assessment on Russian Activities in the 2016 U.S. Elections,” Press Release, Office of Senator Mark R. Warner, May 16, 2018, https://www.warner.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/pressreleases

[4] “Russian Targeting of Election Infrastructure During the 2016 Election: Summary of Initial Findings and Recommendations,” U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, May 8, 2018, p. 4, https://www.burr.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/RussRptInstlmt1-%20ElecSec%20Findings,Recs2.pdf

[5] “Facebook Ads,” U.S. House of Representative Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, https://democrats-intelligence.house.gov/facebook-ads/

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid, p. 2.

[8] Andrew Rettmann, “Next Year’s EU Election at risk of Russian meddling,” EU Observer, January 18, 2018, https://euobserver.com/foreign/140598

[9] Simon Shuster, “How Russian Voters Fueled the Rise of Germany’s Far Right,” TIME, September 25, 2017, http://time.com/4955503/germany-elections-2017-far-right-russia-angela-merkel/

[10] Oliver Bünte, “Facebook löscht erneut Seiten und Accounts der russischen Troll Fabrik IRA,“ Heise Online, April 4, 2018, https://www.heise.de/newsticker/meldung/Facebook-loescht-erneut-Seiten-und-Accounts-der-russischen-Trollfabrik-IRA-4010575.html

[11] Maks Czuperski, “#Election Watch: Final Hours Fake News Hype in Germany: Bots and trolls push vote-rigging claim ahead of German election,” Medium, September 23, 2017, https://medium.com/dfrlab/electionwatch-final-hours-fake-news-hype-in-germany-cc9b8157cfb8

[12] Colin Dwyer “Facebook Plans to Add 3,000 Workers to Monitor, Remove Violent Content,” NPR, May 3, 2017, https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/05/03/526727711/facebook-plans-to-add-3-000-workers-to-monitor-remove-violent-content

[13] “Overview of the NetzDG Network Enforcement Law,” Center for Democracy and Technology, July 17, 2017, https://cdt.org/insight/overview-of-the-netzdg-network-enforcement-law/

[14] The Honest Ads Act, https://www.warner.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/the-honest-ads-act?page=1

[15] “Russian Targeting of Election Infrastructure During the 2016 Election: Summary of Initial Findings and Recommendations,” U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, May 8, 2018, p.5, https://www.burr.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/RussRptInstlmt1-%20ElecSec%20Findings,Recs2.pdf

[16] Sean Lyngaas, “The uphill battle to relaunch State Department’s cyber policy office,” Cyberscoop, May 7, 2018, https://www.cyberscoop.com/state-department-cybersecurity-office-chris-painter-robert-strayer-mike-pompeo/

[17] Annegret Bendiek, SWP Comment, “The EU as a Force for Peace in International Cyber Diplomacy,” SWP Comment 2018/C (April 2018), https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/publication/the-eu-as-a-force-for-peace-in-international-cyber-diplomacy/

[18] “Russian Targeting of Election Infrastructure During the 2016 Election: Summary of Initial Findings and Recommendations,” U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, May 8, 2018, p.5, https://www.burr.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/RussRptInstlmt1-%20ElecSec%20Findings,Recs2.pdf

[19] John S. Davis II, Benjamin Boudreaux, Jonathan William Welburn, Jair Aguirre, Cordaye Ogletree, Geoffrey McGovern, Michael S. Chase, Stateless Attribution (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2017), p. 10.

[20] “Russian Targeting of Election Infrastructure During the 2016 Election: Summary of Initial Findings and Recommendations,” U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, May 8, 2018, p.5, https://www.burr.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/RussRptInstlmt1-%20ElecSec%20Findings,Recs2.pdf