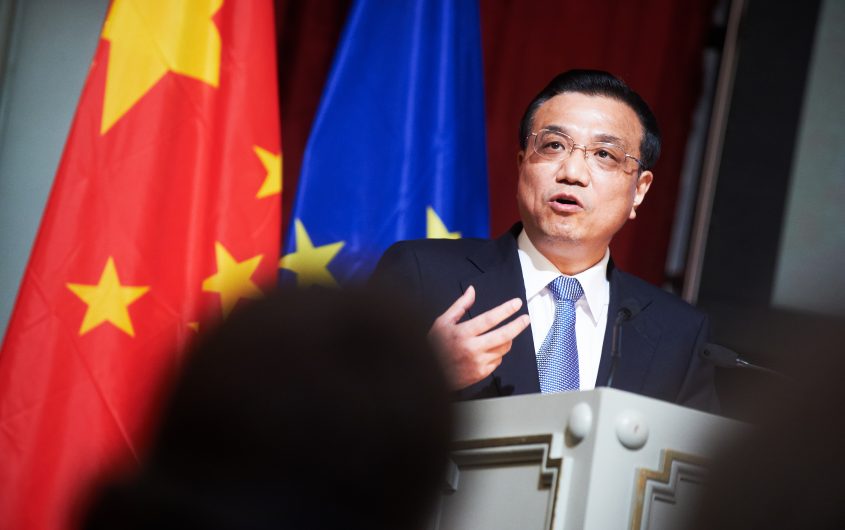

Friends of Europe via Flickr

China’s BRI and Europe’s Response

Angela Stanzel

Institut Montaigne

Dr. Angela Stanzel is a Senior Policy Fellow in the Asia Program and the representative in Germany of Institut Montaigne. Before joining Institut Montaigne in December 2018, Angela worked as Senior Policy Fellow and editor of China Analysis in the Asia Program at ECFR. Prior to that, she worked for the Koerber Foundation (Berlin), GMF (Asia Program, Brussels), and for the German Embassy (cultural section, Beijing). Her recent policy papers include "Fear and loathing on the New Silk Road: Chinese security in Afghanistan and beyond" and "Geoeconomics at an Inflection Point," co-authored with David Livingston.

Her recent publications include: Fear and loathing on the New Silk Road: Chinese security in Afghanistan and beyond (2018), The Trump opportunity: Chinese perceptions of the US administration (2018), The United Nations of China: A vision of the world order (2018), China’s "New Era" with Xi Jinping characteristics (2017), Grand Designs: Does China have a 'Grand Strategy'? (2017), China and Brexit: what’s in it for us? (2016), A hundred think tanks bloom in China (2016), Absorb and conquer: An EU approach to Russian and Chinese integration in Eurasia (2016), Eternally displaced: Afghanistan’s refugee crisis and what it means for Europe (2016).

She was a 2017-2018 participant in AICGS’ project “A German-American Dialogue of the Next Generation: Global Responsibility, Joint Engagement,” sponsored by the Transatlantik-Programm der Bundesrepublik Deutschland aus Mitteln des European Recovery Program (ERP) des Bundesministeriums für Wirtschaft und Energie (BMWi).

During Chinese president Xi Jinping’s December 5 visit to Lisbon, China and Portugal signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) on cooperation in frame of the New Silk Road (“Belt and Road Initiative,” BRI). Both countries also agreed to include Portugal’s southwest port of Sines in the Chinese investment plans. Portugal joins around ten EU member states that have so far signed a MoU with China on the BRI. Italy’s new government is expected to sign a MoU with China as well. These member states’ pledges to cooperate on infrastructure development with China are perceived by other member states with increasing wariness as Beijing is perceived as extending its influence within the EU.

When Xi Jinping announced the New Silk Road for the first time in Astana, Kazakhstan, in 2013, Europeans initially welcomed the Chinese-led initiative. The Silk Road Economic Belt and the Twenty-first Century Maritime Silk Road, which include a northern road corridor and a southern maritime corridor, were intended to connect China via Central and South Asia with Europe. Europeans also hoped to benefit from such massive infrastructure development.

European-Chinese transport connections were soon re-branded to be part of the New Silk Road, then called “One Belt, One Road” (OBOR), such as the Greek Port of Piraeus or rail routes connecting China with Duisburg (Germany), Madrid (Spain), and London (United Kingdom). Soon many more connections were announced such as a railway to the port of Rotterdam or the Belgrade-Budapest railway connecting the port of Piraeus with Central Europe. However, over the past five years the perception in many European countries has changed significantly.

China’s Catchphrase

Many Europeans started to question China’s economic and political strategic motives behind the New Silk Road. They have also become concerned about the way Chinese investment in infrastructure projects is implemented. These concerns increased over the last five years even though China has made considerable efforts to promote the initiative. In particular, Beijing has tried to adapt the New Silk Road’s narrative to attract more countries to cooperate with China and to dispel concerns of countries such as the U.S. and in Europe.

Beijing has tried to adapt the New Silk Road’s narrative to attract more countries to cooperate with China and to dispel concerns of countries such as the U.S. and in Europe.

For instance, the Chinese government changed the original slogan of “One Belt, One Road” around 2015 into the “Belt and Road Initiative” in order to make it sound more like an inclusive initiative rather than a strategy. That this change was meant only for foreign countries is evident in the fact that in the Chinese language the name OBOR remains the same (一带一路 yi dai yi lu). In addition, the BRI no longer only stands for China’s efforts to strengthen hard and soft infrastructure, but has come to include the strengthening of cultural ties with the countries along the Silk Road.

Beijing has also started to offer a “Chinese solution”—a term Xi first used in October 2016—to tackling global challenges, such as shortfalls in global infrastructure, economic development, and cultural ties. China’s apparent solutions to all these challenges are manifest in the BRI. Beijing increasingly stresses its peaceful intentions and soft power benefits and promotes the BRI as a big, nearly global assistance package, aimed at to boosting China’s image as a reliable partner for development.

Beijing increasingly stresses its peaceful intentions and soft power benefits and promotes the BRI as a big, nearly global assistance package, aimed at to boosting China’s image as a reliable partner for development.

As Xi Jinping’s flagship foreign policy initiative, the BRI was even enshrined in the party constitution during the 19th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (October 18-25, 2017). Xi Jinping has since used the narrative of a “shared future for mankind” in particular in the context of the BRI. According to Xi, ”China champions the development of a community with a shared future for mankind, and has encouraged the evolution of the global governance system.”[1] Beijing has promised that countries committed to the BRI will gain greater benefit from Chinese trade, investment, and financing; as Xi stated during the National Congress, China is placing “equal emphasis on ‘bringing in’ and ‘going global.’”

Despite China’s grand catchphrases, it seems as if the more China has tried to find the appropriate BRI language, the more Europeans started to question the substance behind the Chinese narrative.

Europe’s Doubts

Many Europeans believe that the BRI stands for Chinese goals that undermine European interests, such as transparency in public procurement and a level playing field for businesses, as well as European labor, environmental, and social standards. Chinese infrastructure investment within Europe has been only partly successful even within the 16+1 format, the special cooperation format between China and sixteen Central and Eastern European countries. Few countries (such as Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary) have benefited from Chinese investment, while hopes of other member countries to receive investment, in particular for expanding their infrastructure, have been disappointed.

Europeans that have observed Chinese infrastructure investment projects in Africa or Southeast or South Asian countries have started to doubt the real benefit in these projects.

Europeans that have observed Chinese infrastructure investment projects in Africa or Southeast or South Asian countries have started to doubt the real benefit in these projects. China’s slogan of a “win-win” makes Europeans therefore often smirk and respond that this could only mean that China wins twice. For instance, China has often assigned projects to its own state-owned enterprises and often gave work to their own workers from China instead to local workers.

Europeans also see the risk of financial dependencies attached to the BRI and question the conditions of financing BRI projects. China’s infrastructure investment often entails loans rather than aid, raising the threat of a debt crisis in countries that already face debt problems. Some countries have fallen into China’s debt-trap, which could force the debtor to hand key assets to China. In South Asia, for instance, Sri Lanka agreed during negotiations with Beijing in December 2017 to lease its deep-sea port at Hambantota to China for 99 years after becoming unable to pay back debts of more than $8 billion. Despite handing over a strategically important port, Sri Lanka now owes even more debt to China ($13 billion) due to the high interest rates on its existing loans. According to the Center for Global Development, 23 of 68 potential BRI borrowers face the risk of crippling debt.[2]

In Europe, too, for the first time, a country was saddled with a sharp increase of debt after accepting a Chinese loan. Montenegro has taken a loan from China to construct a highway to link the port of Bar to Serbia, a project that might never finish as Montenegro’s debt could increase to 80 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2018.[3] There is some irony to the possibility of Montenegro becoming a EU member state, which would enable the country to then access EU funds to finish the project. This appears, however, only a long-term possibility.

Europeans today largely view the BRI as a scheme that “runs counter to the EU agenda for liberalizing trade and pushes the balance of power in favor of subsidized Chinese companies.”

In sum, Europeans today largely view the BRI as a scheme that “runs counter to the EU agenda for liberalizing trade and pushes the balance of power in favor of subsidized Chinese companies.”[4] This is according to a report signed by twenty-seven EU Ambassadors to China (with the exception of the Hungarian Ambassador). In their report, the EU Ambassadors further criticized that China is using the initiative to pursue its own interests, such as “the reduction of surplus capacity, the creation of new export markets and safeguarding access to raw materials,” and, in short, that China wants to shape globalization to suit its own interests. Previously, German chancellor Angela Merkel had warned that Chinese infrastructure investment in EU countries should not undermine the EU’s China policy. And during French president Emmanuel Macron’s first visit to China in January, he cautioned that the BRI could not be “one-way” and that “These roads cannot be those of a new hegemony.”[5] At the 54th Munich Security Conference at the beginning of February 2018, officials from France and Germany had already called for a unified European response to China’s BRI.

Europe’s Response

The EU recently came out with a unified response to the Chinese BRI, a European connectivity strategy for Asia, unveiled by Federica Mogherini on September 19.[6] The joint communication, titled “Connecting Europe and Asia – Building Blocks for an EU Strategy,” proposes that the EU engages with its Asian partners on infrastructure development. According to the EU’s official narrative, this connectivity strategy is not a response to the Chinese BRI—but it surely appears as if the EU is presenting an alternative. Mogherini presented the strategy as the “European way to connectivity,” which sounds like a counter narrative to the ongoing infrastructure development with Chinese characteristics.

The strategy outlines the EU’s objectives in different areas relating to connectivity, such as in air, sea, and land transportation, as well as in the areas of digital or energy connectivity. More concretely, the aim is to help fill investment gaps in connectivity by strengthening cooperation with the public sector and private investors, as well as national and international financing institutions. This cooperation would include the co-financing from institutions such as the Asian Development Bank and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. In addition, the EU plans to exploit existing and planned EU networks. An important development includes the trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T), which links Eastern European countries and the Caucasus region to economic networks in Asia. Notably, the connectivity strategy emphasizes that cooperation should be conducted in a sustainable, comprehensive, and rules-based way.

Some Europeans criticize that the EU’s strategy sounds too bureaucratic and boring to be able to compete with the Chinese narrative.

The EU’s new connectivity strategy does not sound as catchy as China’s BRI, which evokes romantic connotations of the ancient Silk Road. Some Europeans criticize that the EU’s strategy sounds too bureaucratic and boring to be able to compete with the Chinese narrative. This, however, might not matter as much. Despite China’s efforts to change the name according to other countries’ liking, the BRI has become increasingly unattractive to many Europeans. At the end of the day, substance trumps linguistics and names. Now, the EU will need to deliver on this substance.

The EU’s connectivity strategy will likely not be as grand as the Chinese BRI and only include specific regions in Asia. But by announcing this plan, the EU has sent an important signal to Asian countries presenting cooperation with the EU as an alternative option to the Chinese offer. The result depends on both the EU institutions’ abilities to implement and promote the connectivity strategy and on the member states’ willingness to deliver. The EU and its member states will have to prioritize and allocate its investment strategically in Asia, as well as to scout cooperation with other countries. Similarly, the strategy’s success will depend on the motivation of the private sector to participate.

The EU has a chance now to set standards based on the respect of international rules and sustainable development, as well as the free movement of people, goods, services, and capital.

The “European way to connectivity” appears to be mostly about rules for quality infrastructure development. The EU has a chance now to set standards based on the respect of international rules and sustainable development, as well as the free movement of people, goods, services, and capital. Therefore, implementation will also depend on whether the EU can successfully find partners that comply with the high standards and whether the EU can create synergies and with other countries and financing institutions. The EU will have to open dialogue with a range of countries and agree on cooperation with countries, such as Australia, India, and Japan. There might be potential to cooperate in frame of other infrastructure initiatives, such as the new U.S.-Japan-Australia Infrastructure Fund announced on July 30, a trilateral partnership from three countries to invest in infrastructure projects in the Indo-Pacific region.

Even as an unofficial response to China’s BRI, the EU’s plan does not exclude any partner, meaning China could also be a partner. This possibility would be only viable if China is willing to comply with the standards set by the EU. So far, however, cooperation between the EU and China on the BRI has not been very successful via platforms such as the EU-China Connectivity Platform, an action plan agreed upon between China and the European Commission in 2015, which aims at strengthening information change and finding synergies between European and Chinese connectivity projects. Since the Connectivity Platform has not come out with tangible results as yet, it might not be realistic to expect much cooperation in frame of the EU’s connectivity strategy either.

The BRI has so far shown that perceptions on how infrastructure investment should be carried out are fundamentally different between China and the EU. Disagreements between Europeans and Beijing on the shape of future cooperation under the Silk Road framework had already become apparent when China hosted the first major BRI summit on May 14-15, 2017. Several states, particularly European countries including France, Germany, and Britain, declined to sign a final statement, uncomfortable about its omission of social and environmental sustainability as well as transparency. It is very likely that these differences will have only increased by the time China hosts the second BRI summit in April 2019. Xi Jinping announced during the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) meeting in November that cooperation in frame of the BRI has entered a new phase of full implementation.[7] Europeans will pay attention and observe what this new phase of implementation entails or whether this is another aspect of China’s BRI narrative.

This article is part of AGI’s project on “China, Germany, and the United States: The Strategic Triangle in the Transatlantic Relationship,” funded by the Fritz Thyssen Foundation.

[1] Xi Jinping’s report at the 19th CPC National Congress, October 18, 2017.

[2] John Hurley, Scott Morris, Gailyn Portelance, “Examining the Debt Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative from a Policy Perspective,” Center for Global Development, March 4, 2018,

[3] Noah Barkin, Aleksander Vasovic, “Chinese ‘highway to nowhere’ haunts Montenegro,” Reuters, July 16, 2018.

[4] Dana Heide, et. al., “EU Ambassadors band together against Silk Road,” Handelsblatt, April 17, 2018.

[5] Michel Rose, “China’s new ‘Silk Road’ cannot be one-way, France’s Macron says,” Reuters, January 8, 2018.

[6] Remarks by HR/VP Mogherini, September 19, 2018.

[7] Full text of Xi’s remarks at 26th APEC Economic Leaders’ Meeting, Xinhua, November 18, 2018.