Once Upon a Time, It Was a Man’s World: Women in Conservative Parties in Germany and the U.S.

With a gain of 7.7 percent or roughly four million electoral votes[1] in the recent federal elections, the German Christian Conservatives brought in the best results since 1990. That success has a name: Angela Merkel. One of the most popular chancellors Germany has ever had, she earned her party an outstanding victory with a result that no one would have thought possible only a few years ago. Many pundits, who had already written off the big catch-all parties, now have to reconsider. But what explains the success of Angela Merkel? How does she distinguish herself from the species of politicians that increasingly cause disenchantment with politics? Many explanations are frequently given, among the most popular: Merkel is a natural scientist, is from the former East Germany, and is a woman. Therefore, it is worth elaborating not only on Merkel’s femininity but the fact that the Christian Conservatives in Germany are turning from an old boys club to a party that is increasingly characterized by not just one strong female leader, but by several powerful and visible women in top decision-making positions.

In comparison, the U.S. Republican Party remains strongly male dominated, although a few visible women emerged following the candidacy of the party’s first female vice presidential candidate, Sarah Palin. While conservative women in the U.S. still do not occupy top political positions, the increasing number of female candidates in Republican primaries shows that, at the grassroots level, a growing number of female conservatives are trying to gain access to political office and decision-making. However, the vast majority of these candidates did not succeed in the primaries, leaving the Republican candidate pool—and, hence, elected officials—predominantly male.

By comparing the situations in both countries, this essay will examine the reasons for the differences in female political representation. Did the current German circumstances of strong female representation on the center-right political spectrum occur out of coincidence? Are these circumstances expected to last or are they a transient stage? What needs to be done to strengthen women in the Republican Party and help those succeed who are emerging at the grassroots level?

Recent Developments in the U.S.

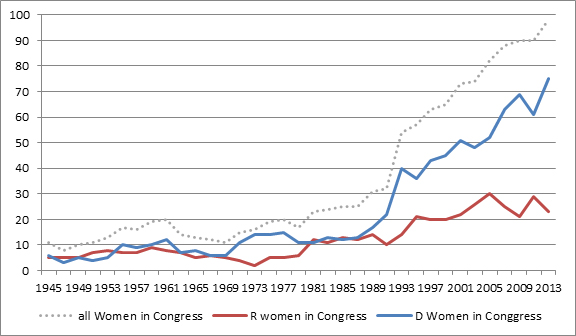

Despite a few prominent front-women, the modern GOP has not built a reputation as a party of women. Both in descriptive and substantial[2] representation the Republicans are lagging behind the Democrats. Democratic women outnumber their Republican counterparts in the U.S. Congress, where 75 female Democrats and 23 Republicans currently serve as Senators and Representatives. As Figure 1 demonstrates, this has not always been the case. The distribution of female office holders in both parties was more or less equal until the 102nd U.S. Congress (1991-1993). Then, due to major gains on the Democratic side and major losses on the Republican side, the number of female Democrats (22) was more than twice as high as that of the Republicans (10). The gap has widened significantly ever since, with more than three times as many women Democrats as Republicans today.

Figure 1: Women in Congress by Party, 1945 – 2013

Historically, the Republican Party has been more supportive of women and women’s issues than the Democrats. Research shows that in the beginning, “it was the Republican Party that was the party of the women’s rights and the Democratic Party that was the party of antifeminism. After the new feminist movements rose in the 1960s and 70s, the parties switched sides.” [3] When it comes to perceptions of which side is more attuned to issues women prioritize today, Democrats are also enjoying a substantial edge. In a 2012 Washington Post-ABC News poll, Americans said the Democratic Party cared more about issues important to women by a 55 percent to 30 percent margin.[4]

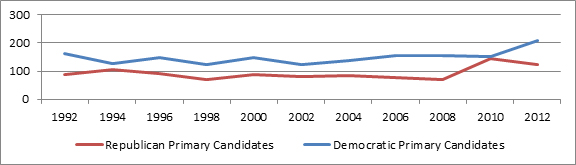

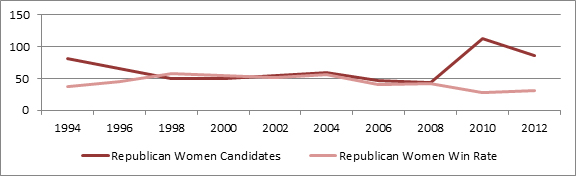

It was all the more remarkable in the 2010 and 2012 elections that a growing number of Republican women ran for office. According to data from the Center of American Women in Politics (CAWP), a record number of women ran in the 2010 Republican primaries (128 for the U.S. House and 17 for the U.S. Senate) as Figure 2 indicates. However, the large number of female primary candidates did not result in a corresponding increase of female Republican officeholders. Instead, Republican women have faced primary problems, particularly in the last two election cycles. Figure 3 shows that while the number of Republican women candidates increased significantly—it more than doubled between 2008 and 2010—the win rate decreased at the same time.

Figure 2: Female Primary Candidates, 1992 – 2012

Figure 3: Republican Women Candidates’ Primary Win Rates, 1994-2012 (U.S. House Candidates)

The increase in candidates might be traced back to the momentum triggered by the Republican vice presidential candidate in the 2008 elections. The unexpected decision by Republican presidential nominee John McCain to name then Alaska governor Sarah Palin as his running mate just prior to the party’s national convention in 2008 electrified the party and alleviated the party’s “anti-woman” image to a degree.[5] Other prominent candidates such as Meg Whitman, Carly Fiorina, and Nikki Haley in the 2010 elections served as role models and may have prompted more women to enter upcoming races. These campaigns could have energized many women who had not seen themselves as being represented by the more liberal feminist organizations that had dominated the electoral scene.“[6]

Recent Developments in Germany

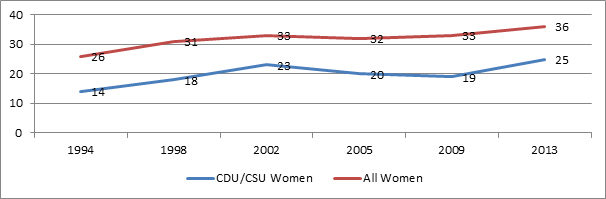

In Germany, conservative women in the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and the Christian Social Union (CSU) have not increased much in number (Figure 4) but rather in accepting the most powerful and visible positions within the party and in executive office. First and foremost there is the chancellor and CDU party chairwoman, Angela Merkel. In addition, two party deputy chairs are female: Ursula von der Leyen, federal labor minister, and Julia Klöckner, former federal undersecretary and now leader of the opposition in the state parliament of Rhineland-Palatinate. Christine Lieberknecht and Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, both female CDU minister-presidents, run the two states of Thuringia and Saarland. Due to the German bicameral system, the minister-presidents exercise considerable federal power through the Bundesrat, the legislative body that represents the federal states at the national level. Finally, the CSU’s most powerful federal position, the head of the parliamentary group in the German Bundestag, is also occupied by a woman.

Figure 4: Women in the German Bundestag, 1994 – 2009

Table 1: Offices Held by CDU and CSU Women

| Angela Merkel | Chancellor; Chairwoman of the CDU |

| Ursula von der Leyen | Federal Labor Minister; Deputy Chair of the CDU |

| Christine Lieberknecht | Minister-President of Thuringia; Member of the CDU Presidium |

| Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer | Minister-President of Saarland; Member of the CDU Presidium |

| Julia Klöckner | Opposition Leader in Rhineland-Palatinate; Deputy Chair of the CDU |

| Gerda Hasselfeldt | Leader of the CSU Parliamentary Group in the Bundestag |

Twelve years after Angela Merkel took over the CDU party leadership, women are stronger and more visible in the party than ever before. Newspapers are calling the CDU the “Party of Strong Women” (WELT)[7] and describe its transition from the “good old boys club to a party that is significantly dominated by women” (Süddeutsche Zeitung)[8]. Besides Merkel, five out of fifteen CDU presidium members and nine out of twenty-one CSU presidium members—the most powerful party elite—are women. However, it is more than the formal positions of these women that puts them in the spotlight. Their visibility and decision-making power outclass many of the long-serving conservative men that have been the face of the CDU since the old days of Konrad Adenauer.

This recent development at the top level, however, shall not condone the fact that both historically and today the Union parties in Germany have not been particularly beneficial to women. For a long time the CDU and CSU were more reluctant to promote the active advancement of women than the Greens and Social Democrats (SPD). While the Greens pioneered the use of gender quotas in the 1980s and the SPD seized on this idea in the same decade, the CDU and CSU were reluctant to follow that path. As Figure 4 shows, even today the parties’ share of women falls below the Bundestag average—despite the fact that the CDU implemented a 30 percent (1996) and the CSU implemented a 40 percent (2010) gender quota for party offices and party lists. Content-wise, the conservatives also took much longer to become broader minded to women’s issues and support more egalitarian views of gender and traditional role ascriptions. Not least did the stronger presence of women in decision-making positions lead the way to more progressive politics regarding family politics, women’s participation in the labor force, and reproductive rights.

Observing the two deviant developments in Germany and the United States one wonders what the different situations are based on. After all, are the two countries even comparable? The following argument attempts to find answers to these questions.

Ideology: While Republicans Are Shifting to the Right, the CDU and CSU Shifted to the Center

The ideological shift to the far right among the Republican primary electorate presents a particular challenge to women candidates, who are often perceived as more moderate and more liberal. In the last primaries, Republican women had to demonstrate strong conservative credentials to succeed. While in the past Republican women often presented a more liberal, rather than traditional, image of gender roles, in the 2010 elections conservative women have taken greater significance.[9]

The CDU and CSU, on the other hand, have undergone a clear shift to the center. Topics like the implementation of a minimum wage, the extension of public childcare, and legally binding gender quotas for women in business used to be firmly rooted in center-left parties. Conservative politicians have now adopted them, with Ursula von der Leyen, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, and Christine Lieberknecht being the center of these movements. While there was an upheaval in the right wing of the CDU and CSU parties claiming conservative values were sold out, the recent successes indicate that elections are more likely to be won through a shift toward the center.

Women Voters Decide Elections

Since women voters have decisive power over who wins or who loses elections, the parties are well-advised to pay attention to their political preferences. Women’s lives have changed dramatically and so have their political demands. Not only have they entered the labor force in much higher rates, but a recent report by the Pew Research Center reveals a sweeping change in traditional gender roles and family life over a few short decades. In the U.S., the number of married mothers who out-earn their husbands has nearly quadrupled, from 4 percent in 1960 to 15 percent in 2011. Single mothers, who are sole providers for their families, have tripled in number, from 7 to 25 percent in the same period. These women—in Germany and the U.S.—are looking for answers and solutions to accommodate their changing needs in the parties’ programs and politics. While tax cuts and social benefits for single-income households have long received political support was appreciated, today there is a growing need for measurements that ensure women’s equal chances to participate in the labor force and enable them to make a living from their income. Consequently, the parties who provide the best solutions to these challenges are the ones attracting women’s votes. In Germany, it was the CDU women that did not flinch from conflicts with their own party and led the way to broaden the mind of the party on topics like childcare, infrastructure, or quotas for women.

In contrast, the female Republican candidates that succeeded in the primaries “came into politics not to pursue traditional feminist issues, such as workplace rights, including equal pay and gender discrimination, but to combat perceived threats to their ability to raise their families unfettered by government.”[10] That leaves the majority of women—even in “red” states—to vote for the Democrats. For example, in New Hampshire, Kelly Ayotte won the Republican primary with a reverse gender gap, winning roughly half of the male voters but only one-third of the states’ Republican women.

Women at the Top Make a Difference

In the thirteen years that Merkel has been her party’s chairwoman, an increasing number of women have achieved top positions, as has been indicated in Table 1. Analyses show that women in powerful and highly visible positions can play an important role in candidate recruitment. Not only may women be more likely to recruit women to run, they are also more likely to know women for these positions and to want more women in office. As long as party leaders are still overwhelmingly male, the predisposition will remain that political elites continue to value men’s political leadership more than women’s.[11]

In the Republican Party, Sarah Palin’s vice president candidacy also helped to herald the start for female candidates. Palin not only acted as a role model, but she also actively endorsed several women in the 2010 elections who might not have gained sufficient attention otherwise. She helped the so-called “Mama Grizzlies,” a group of conservative female Republican candidates, find their voices and get their share of attention and thereby gave definition to a movement “that would otherwise be just a bunch of kooks, or one-offs.”[12] Furthermore, she established a funding apparatus, SarahPAC, that in the week prior to the 2010 mid-term elections had raised $3.4 million and spent $2.4 million in direct contributions to and advertisements on behalf of the candidates she endorsed, many of them female.[13]

Women Candidates Bear New Chances

Common wisdom and research both show that women often get a chance to run when people are looking for change. As Kellyanne Conway, a conservative pollster, stated in the Washington Post, “If you want to convey you are not the firmament of Washington, DC, and ergo of all the problems and out-of-control spending and corruption, you have to say, ‘I’m a Republican woman’ because so few of them have ever been involved at that level.”[14] Angela Merkel’s success can also be traced back to her not being the typical politician. The way she runs the chancellery and the cabinet differs significantly from any of her predecessors—more efficient, quieter, and well considered. It is said that Merkel and her (female) chief of staff have changed the rules of power after they saw the traditional patriarchy in decline.[15] The German population approved of the changes and voted for Merkel and her Christian Conservatives with a 15.8 percent margin to the Social Democrats, who went into the last elections with a male trio composed of the chancellor candidate, the party leader, and the parliamentary group leader. Perhaps politics is not as much of a man’s world, after all.