Used with permission of the artist.

Art and Reconciliation: Beyond the Borders

Nguyen Luong Hai Khoi

Hochiminh City University of Education

Dr. Nguyen Luong Hai Khoi was a Harry & Helen Gray/AICGS Reconciliation Fellow in August and September 2017. He completed his PhD dissertation in the field of Japanese non-dual aesthetics at the Nihon University, Tokyo, Japan, in 2014 and was a visiting researcher at the Hiroshima University, Japan, in 2015. He is the Director of Department of Literature Theory, Faculty of Literature and Linguistics, Hochiminh City University of Education, Vietnam. His research interests concern Japanese social, cultural, and Buddhist philosophy and aesthetics in comparison to those in Vietnam.

While at AICGS, Dr. Nguyen conducted research on his project, “Art and Reconciliation: Beyond the Borders.” Asian countries have a long history of cultural exchanges. Their relations have also been marked by bloody conflicts, which have left some residue of unreconciled historical issues and a need for mutual understanding. In this process of reconciliation, the media, education, and art all have an important role to play. However, in Asian media and in educational and political systems, Asian countries are commonly viewed as a political imagination illustrated through the cultural creation of “historical narratives.” In this way, “Japan,” “China,” “Korea,” “Vietnam,” or “Asia” have been viewed as “imaginative pictures” rather than as political realities. These lenses for seeing one another often have an ideological component that reduces the complex nature of reality in order to serve some nationalist propaganda purpose. Dr. Nguyen’s research analyzes the art work “RE/COVER” of Phan Quang, a contemporary artist in Vietnam. He examines the capacity of artistic creativity to help us to recognize the both history and the reality of Vietnam-Japan relations.

Victim Narratives and Ethnic Nationalism in Asian Artistic Expressions

Relations between Asian countries are influenced by historical consciousness. The expression of that consciousness, which is extremely politicized in Asia, plays an important role in building or destroying modern relationships.

Art is one way in which the historical consciousness is depicted or expressed. At present, there are many artistic expressions of animosity toward each other in Asia. For example, a 2005 Japanese comic book (manga) entitled “The Hate Korea Wave” (Kenkanryu or嫌韓流) expresses anti-Korean sentiment. This manga defames Korea, sings the praises of Japanese colonization in Korea, and argues that Japan created the South Korea of today. It was a best seller in Japan in 2005. Another example is “The Hate China Wave” (Ken Chugokuryu or『嫌中国流』) released in Japan in 2008. This work focuses on China’s wrongdoings and refutes the 1937 Nanjing massacre. Two comic books were published in 2006 in South Korea, responding to “The Hate Korea Wave”: “The Hate Japan Wave” (Hyeomillyu or혐일류). The books criticize sexuality in Japan, Japanese colonial rule in Korea, Japanese militarism, the Yasukuni Shrine, and Dokdo/Takeshima territorial disputes. In the Chinese case, the country has built an anti-Japanese film industry, by some estimates having made more than 200 anti-Japanese films in 2012. Those Chinese films depict the “shameful” Japanese as people deserving to die. While Chinese censorship has declared a lot of subjects off limits, anti-Japanese themes are not among them.

There are also many anti-Vietnam expressions in China. Recently, a Chinese cartoon entitled “Untold history of the war against Vietnam” (越戰軼事) argued that the Chinese attack on Vietnam in 1979 was an act of “defense” not an “invasion.” The Vietnamese are depicted as barbarians who used naked women to attack Chinese soldiers while Chinese soldiers are gentlemen who continuously win all the battles. In Vietnam, there are also many artistic expressions against China, especially paintings ironically depicting China’s ambitious claim to the South China Sea.

South Korea also only remembers the pain inflicted by Japan in World War II but does not remember what its own army did in South Vietnam in the Vietnam War. Koreans do not talk enough about women serving the U.S. troops in the 1960s, and only focus on the Japanese issue of comfort women. Japan remembers its suffering from American atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki but does not have the same attitude about what it did in other Asian countries. The Vietnamese tend to talk about the Chinese invasions but do not remember that Vietnam also did the same with the Champa Kingdom historically. China likes talking about what Japan did in its country from the nineteenth century to World War II, but does not remember what it has done in Tibet and other Asian countries.

It seems that Asian countries tend to talk about themselves as victims but not as wrongdoers. They talk about the wrong doing of other countries but do not want to talk about what they did.

Every country has its own bad things and good things, but in some cases (like those mentioned above), emphasis on the bad things can be dangerous. When the expression of those bad things happens as if they are the unchanging and certain, it implies that the country they hate has nothing good about it and therefore their own value is higher than the other country. The most dangerous thing is that the depiction of another country or ethnicity as valueless also implies that it is no problem to eliminate it. That is to say, those kinds of artistic expressions can be used for a future war.

Memory, Forgetting, and Justice

If we create reconciliation by forgetting or ignoring history, that so-called reconciliation violates our sense of justice. That kind of reconciliation also makes political and cultural constructions of images of other Asian countries possible. Those political constructions are created by certain political contexts, and when those political contexts change, those images also can be changed. After normalization with Japan in 1972, China deleted the Japanese historical problems from Chinese history textbooks. South Korea did the same in Park Chung-hee’s presidency due to economic concerns. But now that both China and South Korea have become powers in Asia, those historical issues have reemerged.

Case Study: Phan Quang’s “RE/COVER”

On “RE/COVER”

There is much scholarly research on the political, economic, educational, and cultural solutions to reconcile those historical conflicts in Asia. Regularization of high-level diplomacy, mutual appreciation, creating an Asian security dialogue mechanism, the roles of civil society, business, and academic circles are all often mentioned. Another perspective, introduced here, is the aesthetic and philosophical point of view through “RE/COVER,” an artwork on Japanese-Vietnamese historical relations by Phan Quang, a Vietnamese contemporary artist.

Phan’s “RE/COVER” relates to a hidden history between Japan and Vietnam. Phan’s work could open the door to personal connections beyond nationalist perspectives or identity-based politics. It could help us to recognize the history and the reality as a whole; and aid us in avoiding the manipulation of historical and realistic images as tools for political aims that reduce the diversity of reality. His historical approach could contribute a new perspective to make reconciliation in Asia possible.

The Japanese occupied Vietnam from 1940 until the end of World War II in 1945. After Japan surrendered to the United States in August 1945 and Ho Chi Minh, the nationalist and communist leader of Vietnam, declared Vietnamese independence from Japanese occupation and French colonial regime, about 700 Japanese soldiers remained in Vietnam. Those Japanese soldiers helped to train Ho Chi Minh’s troops to fight the French forces in the First Indochina War from 1946 to 1954. They became “Vietnamese soldiers” and took Vietnamese names. Some of them married Vietnamese women and have family in Vietnam.

After Vietnam defeated France in Dien Bien Phu in 1954, Vietnam fell into the Cold War and was divided into two countries, North and South Vietnam. The Japanese government forced many former Japanese soldiers to leave Vietnam and return to Japan without bringing their wives and children. Most of those Japanese soldiers never returned to Vietnam, although some fought to reunite with their families.

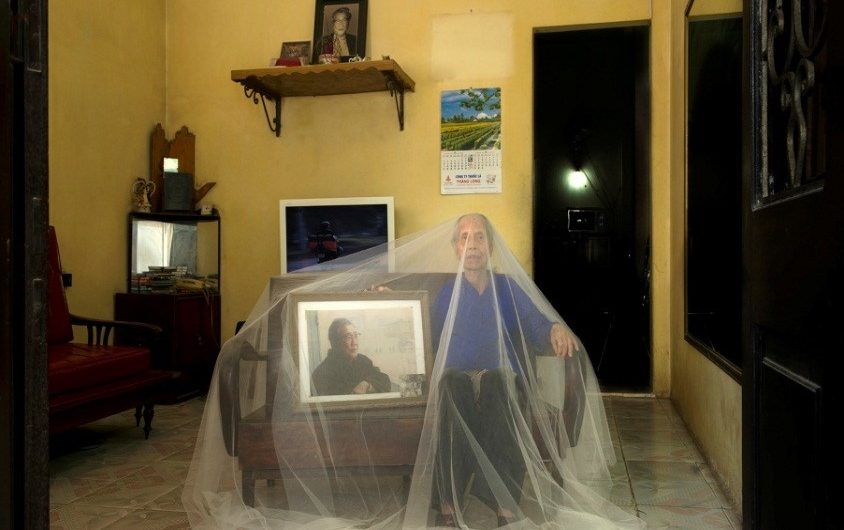

Phan Quang has visited these families many times, becoming like a family member, and has been permitted to take photographs of them. His “RE/COVER” is a series of photographs about those Vietnamese women and their families. Phan covers the people in these photographs in a large piece of white chiffon fabric that was produced in 1954 in Kyoto.

The following are some his photographs:

How to Open a Journey to Reconciliation?

In 1940, the Japanese fascists invaded Vietnam. In 1945, Vietnam declared independence and then conducted a war of resistance against France. That was the approach of “Big History”: the historical picture of the Japanese commanders that led the Indochina Invasion from 1940 to 1945 like Nishimura Takuma and Nakamura Aketo, of the great Vietnamese leaders that commanded the fight for independence and built Communism like Ho Chi Minh and Vo Nguyen Giap, of the French rulers of Indochina like Jean Decoux and Henry Martin. In schools and in the media, we have always heard about those “big stories,” about the “big picture” of the “era” that were controlled by those “big characters.”

The human realm of those great historical pictures has its own massive borders. In the Vietnamese space, the border was built by “Fascism,” “Colonialism,” “Imperialism,” “Capitalism,” “Independence,” “Socialism,” and so on. In the Japanese space, the border was built by “the Great Japan,” “the slow-developing Asia,” “Western people,” “the Emperor,” and others. In the French space, the border was “the Great France,” “the Far East,” “Civilization,” “Democracy,” “Equality,” “Freedom,” “Compassion.” In the big historical picture, people were shaped by those borders. It was a default that “the era” would set their identity. According to those parameters, a Japanese soldier could kill French and Vietnamese to build “the Great East Asia,” a French soldier could slay Japanese and Vietnamese to achieve “civilization,” and a Vietnamese soldier could kill French and Japanese to regain “independence” and build “socialism.” They did it with a high awareness of morality that lies inside the borders drawn inside their minds.

It narrates a tale of love, loss, and pain created by historical and political borders, but “RE/COVER” is beyond all borders. Phan does not look at the big pictures, big characters, and big concepts to see the history. He looks at history through small persons who were not any match for the big politicized historical picture. The big history eliminated them. Those Japanese soldiers were seen as traitors by Japan (and to fix it, they were forced to return to the old border in order to end that betrayal), and they were also seen as invaders by Vietnam (so that they needed to leave, even though they had some historical attachment to the Vietnam People’s Army, training it in modern fighting skills). Even Vietnamese wives and children were not recognized by both governments. They were neither a Vietnamese citizen nor a Japanese citizen. They were the ones expelled from all spaces made by political and cultural borders.

Among the photographs of “RE/COVER,” I am most interested in this one.

Mrs. Nguyen Thi Thu has her deceased Japanese husband—Mr. Ngo Tu Cau (Uwaka as Japanese name)— on the Vietnamese altar. It is not a Japanese space, but it is also not really “non-Japanese.” It is a Vietnamese space but it is also not really “Vietnamese.” This space does not follow any definition of the big history or political concepts made up by any big historical characters. It has been the space of micro-history that was created by the little people. Using these peoples’ perspective gives another, experimental way of using history.

According to Nguyen Nhu Huy, a curator in Ho Chi Minh City, Phan uses contemporary art as a way to explore reality and give us a new perspective to see history. Phan does not comment on the reality but penetrates the history as a part of reality to show the hidden aspects of history. He does not reduce the history to a simple object that we can express with some cultural discourse to meet political aims.

By covering the characters with the chiffon, Phan helps us to look at the reality from another perspective. That perspective is not hindered by any forms of reality such as colors, shapes, pictures, or sounds—the factors that cause the borders in our minds. It transcends those forms and allows us to see the supreme reality which is not divided by the borders in our minds. No matter if the character is a farmer or worker, Vietnamese or Japanese or “anyone,” the spectators can easily trespass their borders to contemplate the human substance, the end point of a journey that Phan would like to take them to. Capturing a form but not getting stuck in that form in order to reach its abstract substance is the way to see this work.

That approach toward history could help us to recognize the history and reality as a whole, as well as to avoid manipulating historical and realistic images as tools for political aims. It explores an artistic and realistic approach of the reality of Asian countries beyond any artificial or political point.

That kind of consciousness of history could open a journey to reconcile the violent past and prevent future conflicts. In January 2017, Suzuki Akiko, a journalist at Japan’s Asahi Shimbun newspaper, interviewed Phan about “RE/COVER” and introduced the artwork in the Asahi on March 2, 2017. After that, Japanese Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko visited Vietnam and made a landmark gesture of reconciliation when they met Vietnamese women abandoned by their Japanese soldier husbands. I think that it is a beautiful meeting to end this story.