The EU-U.S. “Oil Weapon”

Thomas O'Donnell

Hertie School of Governance

Thomas O’Donnell was a DAAD/AICGS Research Fellow in April and May 2015. He is an academic, analyst, and consultant with expertise in the global energy system and international relations. At AICGS, his focus is “U.S. Expert Perspectives on German Energy Vulnerabilities.” Dr. O’Donnell’s teaching and research have encompassed the EU and Russia, Latin America, the Middle East, China, and the USA. His PhD is in nuclear physics from The University of Michigan at Ann Arbor; for the past 15 years he has primarily taught post-graduate international relations and development with a focus on energy and natural resource issues, including at The University of Michigan, The Ohio State University, at The New School University’s JJ Studley Graduate Program in International Affairs (NYC), and at Freie Universität’s JFK Institute (Berlin). At his blog, the GlobalBarrel.com, he follows issues of energy and international affairs, and he also writes frequently for the IP Journal (Berlin), Americas Quarterly (NYC), and Petroguía (Caracas).

Throughout 2008-09, Dr. O’Donnell was a U.S. Fulbright Scholar and Visiting Professor in Caracas at the Center for the Study of Development (CENDES) of the Central University of Venezuela (UCV). He is a Senior Analyst at Wikistrat and consults with various other geopolitical, business-intelligence, and advisory firms. Before doing his PhD, Dr. O’Donnell spent a decade working in U.S. industry, gaining technical experience in automobile manufacturing, railway operations, large-scale HVAC, and in power generation. He has also worked as a radiation safety and health-physics officer at a research nuclear reactor and in medical and other settings. In experimental nuclear physics, he conducted basic research at several particle-accelerator and national laboratory facilities in the U.S., Japan, and elsewhere; and is author or co-author on about 40 peer-reviewed scientific papers. Since 2012, he has lived in Berlin with his wife and youngest children. He speaks English, Spanish, and functional German.

Figure 1: Presidents Rouhani of Iran and Putin of Russia holding discussions

Since Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin, decided to annex Crimea and back east Ukrainian separatists with troops, many have worried he might use his “energy weapon” to counter U.S.-EU sanctions, as Russia supplies around a third of the EU’s natural gas imports. But what about Russian retaliation in the oil sector?

That’s hard to imagine. While gas is marketed in bi-lateral, pipeline-mediated relationships, oil is not. It’s liquid, fungible, and marketed in a unified open market—“the global barrel,”[1]—which means there are no bi-lateral oil dependencies.

So, when EU leaders were cajoled by Germany’s Angela Merkel into joining the United States in applying sanctions, Russia could do little to retaliate from within the oil sector. In reality, it is the EU and the U.S., not Russia, that have an “oil weapon” in hand. And, the flurry of Russian oil diplomacy with OPEC, Iran and China over the past couple of weeks has a distinct whiff of desperation to it.

Consider OPEC: Here, Igor Sechin, chief of oil-giant Rosneft, and other officials have been talking with OPEC members from Venezuela to Saudi Arabia. It’s difficult to see what Russia hopes to gain here. Moscow coordinating with OPEC to cut production and boost the price of oil seems unlikely. Russia has never cooperated with OPEC cuts, even though OPEC has occasionally reached out to Moscow. For example, in 2008, Russia promised to cut production in support of OPEC, but instead increased output in 2009, freeriding on OPEC’s cuts.

Last November, when Saudi oil minister Al Naimi was repeatedly warning that OPEC could not cut enough oil on its own to reverse falling prices, he met with his non-OPEC Mexican and Russian counterparts. However, both demurred from joining any OPEC cut.[2] So, instead of cuts, the Saudis convinced OPEC the only alternative was to increase production, forcing prices even lower to drive higher-cost producers from the market, thereby at least boosting OPEC’s market share.

Today, Russia’s oil-export revenues are under such pressure from sanctions and low prices that the country has taken to “consulting with” (i.e., lobbying) the Saudis to change OPEC policy. However, even if Putin were to promise to cut production together with OPEC in order to push the price back up—Al Naimi would rightly be skeptical. According to Al Naimi, the reason the Russians gave for not being able to cut production last November was that the low-temperature of their west Siberian fields dictates Russian production cannot be cut back without ruining those fields. [3] So, unless Siberia has recently warmed up, the only way Putin might undo OPEC’s policy is to cut his support for Syria’s Bashar al-Assad, which the Saudis have publicly suggested.

Then there is Iran: In mid-April Putin once again announced a deal to barter Russian food and industrial goods for Iranian oil (he has gone back and forth with this scheme for over a year). He also lifted the ban Russia imposed in 2010 on exporting its S-300 missile systems to Iran while the P5+1’s nuclear negotiations are still underway. On one hand, Putin’s dual offers to Iran work to embolden it in the still-continuing nuclear negotiations, thus possibly undermining U.S.-EU efforts (although Russian manufactures say it would take at least six months to fill the missile order once it’s received). Yet, on the other hand, the barter would appear to place Russia first in line for Iranian trade when, and if, a nuclear deal is completed and Iran’s sanctions are lifted. However, there is no need to spend too much time unraveling a Russian policy that is apparently at odds with itself as, almost immediately, Russia and Iran each issued caveats to the barter deal, with a Russian minister even denying oil would be involved.[4] Once again, one senses an air of desperation here.

So, too, with China: There is a promising new large oil field, Vankor, in the northern Siberian tundra. U.S. and EU sanctions, imposed in March 2014, block western companies from participating in developing unconventional oil fields, including in Arctic waters, deep offshore fields, and shale strata, all of which Russia was counting on to replace its declining conventional west Siberian fields. So, in September, Putin invited the Chinese to directly buy a share and help to develop the Vankor field.[5]

This was seen as highly unusual, as Russia has rarely given foreigners such direct ownership stakes. However, as Reuters reported last week: “Vankor [is] key to Russian policy of tapping new regions.”[6] Aside from the much-needed foreign capital (note that U.S. and EU sanctions also prohibit Russian banks and firms access to long-term western financing), the sad reality is that Russian oil firms lack the technology and managerial-organizational capacity to develop unconventional fields without western firms’ assistance. In other words, Putin’s failure to re-industrialize Russia also hamstrings Russia from remaining a competitive petrostate.

Here too, in this China deal, lurks an air of desperation.

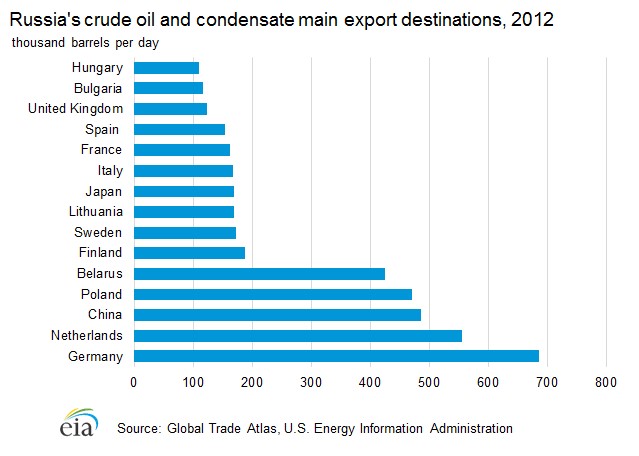

Figure 2: Russia Supplies More Oil to Germany than to Any Other Country

In the end, despite the fact that Russia has perennially been among the world’s top two or three oil exporters, supplying about 36 percent of the EU’s crude oil in 2013,[7] and almost 30 percent of Germany’s oil[8] (indeed, for decades, Germany, the EU’s leading economy, has remained more “dependent” on Russian oil than any other western European state), no person knowledgeable of how the global oil sector functions worries about any potential Russian “oil weapon” against Germany or the EU.

So where does this leave matters? For one thing, Putin is certainly aware that should he decide to wreck the Minsk ceasefire by grabbing Mariupol or a significant amount of other Ukrainian territory, the United States and the EU would almost certainly ratchet up their energy sanctions to the next obvious level: blocking participation of western firms from producing conventional Russian oil. Such sanctions would be devastating.

[1] See: http://GlobalBarrel.com

[2] Thomas O’Donnell, “Oil Price Collaterals: The new Saudi strategy shakes Russia, Iran, and Venezuela, but they are not its real targets” IP Journal, 2 February 2015, https://ip-journal.dgap.org/en/ip-journal/topics/oil-price-collaterals

[3] Interview with Saudi oil minister Al Naimi, 21 December 2014, conducted by MEES (Middle East Economic Survey) reprinted in OilPro at http://oilpro.com/post/9223/mees-interview-saudi-oil-minister-ali-naimi

[4] “Russian, Iranian companies discuss barter deal terms- minister,” Reuters, 15 April 2015, http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/04/15/iran-nuclear-russia-novak-idUSL5N0XC2K720150415

[5] “INSIGHT-Learning Mandarin in the tundra: Russia invites China into oil business,” Reuters, 8 April 2015, http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/04/08/russia-rosneft-china-idUSL5N0X51AG20150408

[6] Ibid.

[7] IEA, Antoine Halff, July 2014, using 2013 data; Slide 16: http://www.eia.gov/conference/2014/pdf/presentations/halff.pdf

[8] Deduced from data at EIA report, http://www.eia.gov/countries/country-data.cfm?fips=gm