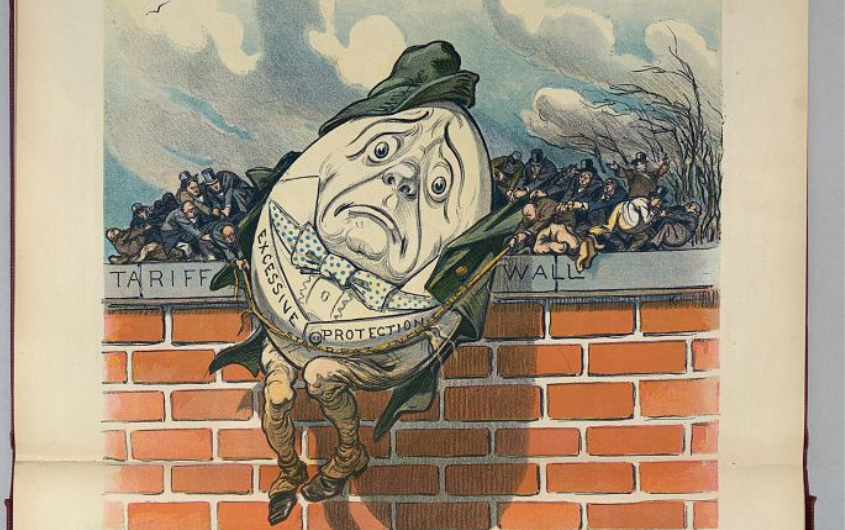

Keppler & Schwarzmann via Library of Congress

Smoot-Hawley, McKinley, or a Brave New Trading World?

Edward Knudsen

University of Oxford

Edward Knudsen is a DAAD/AGI Research Fellow in Fall 2024.

Edward Knudsen is a doctoral researcher in international relations at the University of Oxford, a Research Associate for the Centre for International Security at Berlin’s Hertie School, and an Affiliate Policy Fellow at the Jacques Delors Centre. His research focuses on the political economy and economic history of the United States and Europe in the twentieth century, specifically international sanctions, organized labor, and the role of memory in international economic policy. Previously, he worked for the U.S. and the Americas Programme at Chatham House in London. He holds a master’s in international political economy from the London School of Economics and Political Science and a bachelor’s degree with majors in history and economics from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

His research at AGI will focus on how policymakers understand the legacy of protectionism in the United States, especially the infamous 1930 Smoot-Hawley tariff. Using the concept of historical memory, he examines how specific societal understandings of interwar economic policy were developed, who they benefitted, and who continues to advocate them today. Combining archival research with expert interviews, his research explores how and why we “remember” certain events and not others—as well as what effect this has on contemporary policymaking.

He has published academic articles on political economy and governance in the United States and EU with the journal Global Policy, opinion pieces in outlets like Project Syndicate and the Berlin Policy Journal, and is currently finishing a book on soft power with Oxford University Press. He also hosts the podcast Spaßbremse, a critical take on German politics and history, in English.

Historical Analogy and the Future of U.S. Trade Policy under Trump

Trump and trade history

MAGA is coming back to the White House—but the 2024 vintage of “Make America Great Again” is even more retro than the 2016 edition. Indeed, while the slogan on the famous red hats may be the same as it was eight years ago, the movement’s ideas of exactly when America was “great” has shifted back roughly one half-century. Whereas Donald Trump’s earlier campaign glorified the 1950s as the peak of American power and prosperity, his latest run for the White House harkened back to an earlier era that is less prominent in the popular imagination—the “Gilded Age” of the 1890s.

This distant callback is especially clear in the realm of international trade. Trump has openly expressed his admiration for the “highly underrated” President William McKinley and praised the high tariff policy that he claimed made the United States “probably the wealthiest it ever was.” His incoming commerce secretary, Howard Lutnick, went even farther in expressing his reverence for the twenty-fifth president and the economic policies he championed. Asking a Madison Square Garden audience “when was America great?” Lutnick quickly and emphatically answered his own question: “The turn of the century!” Justifying his decision to reach back 125 years for a historical example, he elaborated that around 1900, “our economy was rockin’, we had no income tax, all we had was tariffs, and we had so much money!”

Critics of Trump’s protectionist provocations have been keen to poke holes in these historical parallels, suggesting that his account of the 1890 McKinley Tariff (which increased average duties across all imports from 38 to 49.5 percent and may have contributed to an economic downturn) is inaccurate or that the industrial and agricultural economy of the 1890s is a poor analogue for today’s advanced and service-intensive system. These critiques certainly have merit, but to focus on the minutiae of historical analogies is to miss more important questions regarding why and how references to the past are used in trade debates—as well as what effect they might have on policy outcomes.

The politics of the past in U.S. trade policy

It would be tempting to single out Trump for his use of shaky history to justify his chosen policies. Rather than a peculiarity of Trump’s trade rhetoric, however, this type of argumentation is typical. Indeed, his administration’s focus on McKinley’s tariffs illustrates a larger point about the relationship between our collective memory of economic history and contemporary policymaking: that hegemonic policy regimes always rely on specific (and often distorted or one-sided) readings of the past. Aside from recent public comments, archival records of congressional debates and presidential speeches also clearly demonstrate that using a mythologized view of trade history to legitimate a desired policy change is the rule in U.S. trade debates, rather than the exception.

For decades, the legitimating historical narrative of U.S. trade policy remained relatively stable. From the 1940s to the mid-2010s—as the United States pursued a broadly multilateralist and liberalizing trade agenda—the perceived disaster of the 1930 Smoot-Hawley tariff formed the central reference point in debates about international economic relations. As late as 2017, the U.S. State Department referred to it as a “symbol” and “watchword” for protectionism.

The tariff itself, however, was more the product of partisan politics and self-interested congressional negotiations than any grand protectionist or isolationist vision. High tariffs were the norm in the United States during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, with prominent figures like Alexander Hamilton authoring early theoretical justifications for industrial policies like subsidies and trade barriers. In the 1928 presidential election, Herbert Hoover of the Republican Party—which represented northern industry and generally favored higher tariffs—ran on a platform of increased protection, despite the U.S. trade surplus at the time. Passed in a Republican Congress against the objections of over 1,000 economists, Hoover signed the bill in June 1930, eight months after the start of the Great Depression. The bill’s actual economic impact on the Depression is now thought to be minimal, but it did not aid the U.S. recovery and did result in retaliatory trade measures as well public opinion souring on high tariffs. In response, the Roosevelt administration—with the encouragement of Secretary of State Cordell Hull—signed the Reciprocal Tariff Agreement Act (RTAA) in 1934, which authorized the president to negotiate reciprocal reductions in duties up to a maximum of 50 percent.

Although the RTAA solved many of the problems exemplified by Smoot-Hawley, proponents of free trade after World War II lambasted every president from Truman to Trump as “going back” to the dark days of interwar protectionism, invoking the 1930 tariff countless times to advocate for their position. While the free traders generally prevailed until the 2010s, detractors sought to undermine the policy consensus through two main strategies of disputing the dominant reading of history. In what I refer to as the “contest of analogy,” they argued that Smoot-Hawley was not a fitting comparison for whatever policy was currently being debated. Additionally, in what I refer to as the “contest of memory,” they frequently tried to qualify the negative effects of Smoot-Hawley, suggesting that catastrophizing accounts of its contribution to the Great Depression and World War II were either exaggerated or outright false.

More recently, as both the Trump and Biden administrations have sought to chart new courses in U.S. foreign economic policy, they have turned to the past to legitimate their desired shifts in trade policy. For its part, the Biden team’s “worker-centered trade policy” sought to unearth the largely-forgotten legacy of the abandoned International Trade Organization (ITO) and corresponding 1948 Havana Charter to serve as inspiration for their approach. The labor and environmental protections included in the ill-fated ITO could serve as a model for a renewed, “race-to-the-top” multilateralism, they argued. Trump—while still seeking to break with the pre-2016 liberalizing consensus—now embraces a more unilateralist and aggressive approach to trade abroad, combined with a leaner state at home. Accordingly, the McKinley era of high tariffs and low domestic taxation serves as a useful historical justification for the incoming administration’s proposals.

While both approaches have made some headway in undermining the “neoliberal” trade consensus and the “Smoot-Hawley myth” on which draws legitimacy, these challengers have been less successful at establishing their own dominant reading of the past—or a corresponding hegemonic policy regime. Although there has been renewed discussion of the Havana Charter and McKinley Tariffs in policy circles, neither has reached the iconic status in popular culture that the Smoot-Hawley Tariff has achieved in the U.S. collective memory.

Using a mythologized view of trade history to legitimate a desired policy change is the rule in U.S. trade debates, rather than the exception.

The lack of a new hegemonic historical trade narrative does not mean that either of these insurgent “memory battles” is doomed to failure, however. Indeed, Smoot-Hawley was not always the central reference point—accompanied by perceived unambiguous policy lessons—that it eventually became. In the 1940s and 1950s, debates in the U.S. Senate reflect a multiplicity of views about the relevance and meaning of the 1930 tariff. Only later in the twentieth century did the current, pro-liberalization, interpretation become dominant. This suggests that just as new historical regimes can fall and new ones put in their place, the opportunity for a new hegemonic approach to trade policy—and the corresponding historical basis for it—remains open to contestation. Political struggles over the course of decades will determine which, if any, of these narratives can cement itself as the new historical “common sense” in the same way that Smoot-Hawley once did.

2008 and the specter of interwar protectionism

Following the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, fears of a resurgence of protectionism akin to the “beggar-thy-neighbor” policies of the 1930s became widespread. In order to ward off the perceived threat of new tariffs, economic liberals employed what Gabriel Siles-Brügge calls the “Smoot-Hawley myth,” or the idea that the Great Depression was caused (or at least severely worsened) by the 1930 tariff act. Others took this causal argument a step further, arguing that Smoot-Hawley indirectly contributed to the outbreak of World War II. For example, former WTO Secretary-General Pascal Lamy claimed that Smoot-Hawley was a cause of the Depression, which was “surely among the factors contributing to the geopolitical instability that in turn led to the Second World War,” echoing Cordell Hull’s belief that “wars were often caused by economic rivalry” and that by removing “international obstacles to trade, we would go a long way toward eliminating war itself.” A number of scholars have taken issue with these historical arguments, but they are still wielded as a potent rhetorical tool. Indeed, events surrounding the Great Depression, including Smoot-Hawley, have become a “black mirror,” emerging as the “key reference point” for future economic events.

On the international level, a total of seven different statements from the G20 between 2008 and 2012 employed references to interwar protectionism and Smoot-Hawley. WTO Secretary General Pascal Lamy also referenced the 1930 act at least eight times and even had a picture of the two men for whom the tariff was named in his office to show to guests. In the end, these efforts were largely successful—at least for the subsequent decade.

The one-sided view of Smoot-Hawley that was so commonplace after 2008—namely that it was an unmitigated disaster and that any adoption of trade barriers risked a full return to interwar-style protectionism—was a relatively recent innovation, however. Indeed, from the 1940s to the 1980s, U.S. policymakers frequently debated the meaning of Smoot-Hawley, arguing over its effects and whether it was a suitable comparison for contemporary trade discussions. Only from the 1980s onward, when the personal memory faded into cultural memory and the United States needed a clean historical narrative to justify liberalization in the face of a rising trade deficit, did the hegemonic meaning of the 1930 tariff emerge. This understanding represented a belated triumph of Secretary of State Cordell Hull—a fervent free-trader who served under Franklin Roosevelt—who helped popularize both the catastrophic economic narratives around Smoot-Hawley as well as the idea that it contributed to the outbreak of war.

The widespread use of references to Smoot-Hawley long after any living policymakers begs an obvious question: is this analogy used only to legitimate preexisting preferences or does the supposed “lesson” of interwar protectionism actually affect the way trade experts see the world? Unsurprisingly, and perhaps unsatisfactorily, the answer seems to be a mix of both. Based on over a dozen interviews with current and former members of the U.S. government, German ministries, and international economic organizations, I have found a roughly even mix between the justificatory and informative theories of analogical usage. For example, one longtime senior figure at the United States Trade Representative (USTR) said that atonement for Smoot-Hawley formed the “core basis of what we do” while a former top-level figure at a multilateral institution openly admitted to using Smoot-Hawley for purely rhetorical purposes, despite knowing that the precision of the comparison was shaky at best. In these conversations, one pattern did become clear—historical references used in elite-elite conversations tend to be believed more earnestly, while public statements about the “lessons of the past” are used more frequently as argumentative ornamentation.

Contesting the meaning of Smoot-Hawley

Hull’s arguments may now be commonly accepted, but records of U.S. Senate debates in the 1940s indicate that in the decade following Smoot-Hawley, it was not primarily seen as a disaster due to tariff levels, but rather due to the unfairness of the legislative process that crafted the bill. For example, in 1943, Senator Clark of Missouri lambasted the “horse-trading” though which industries lobbied for protection, with several other senators criticizing the “logrolling” that accompanied the bill’s crafting. This anticorruption, rather than ideologically anti-tariff, argument was one of the most popular cases for freer trade at the time.

To be sure, a number of senators criticized the economic effects, but these frequently were seen as a problem of degree, not kind. On June 2, 1943, as senators were debating an amendment that would partially restore some protectionist measures, one fretted that “the Smoot-Hawley tariff, many of the excesses of which have been pared down by the Hull program, would be automatically restored.” The next day, the “excesses” of Smoot-Hawley were again critiqued, rather than the concept of tariffs in general—which several senators saw as acceptable at lower levels. One senator criticized restrictions on tariff levels as “a surrender of the taxing power,” preempting battles over Trade Promotion Authority that were to follow in subsequent decades.

Advocates of protecting U.S. industry also targeted what they saw as simplistic narratives of the past, with one senator calling out the “men in high places who…have the cockeyed notion that the Smoot-Hawley Tariff caused the depression, when, if they had looked up the history of the period, they would have seen that the depression was under way throughout the world and in the United States.” Another 1945 speech pointed out that “The deflation came first, and our too-strict tariff policy in the Smoot-Hawley law came afterward.” In 1953, a senator lamented that “for 20 years we have heard the statement that the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was a major cause of the depression [but] that act was not passed until 1930, and the depression came along in 1929.” Expressing similar frustration in even clearer terms, another senator remarked that “if we are going to take the position that every single tariff increase must be uniformly opposed because it might be regarded as a symptom of so-called Smoot-Hawley protectionism, then we should abandon the whole procedure of tariff hearings.”

Still, the perceived disaster of interwar trade policy made defense of tariffs difficult. Rather than directly defend the 1930 tariff, Senator Robert Taft of Ohio sought to narrow the terms of debate beyond parallels to the past, arguing that “The Smoot-Hawley law might have contributed [to the Great Depression] and I think the rates in that law were too high…I am not defending those rates today, [but] I am defending rates 50 percent lower than the Smoot-Hawley rates” that were under discussion. Revealing how personal memory can begin to fade to collective memory, one senator deferred to the historical interpretation of his more senior colleagues, saying, “I have been told by Senators who were here that the Smoot-Hawley Act contributed to world depression and to world war.”

Regardless of the future of U.S. trade policy, the basis of it will not only be determined in the Oval Office, negotiating table, or halls of the WTO—but also in the memories and analogies that are used to legitimate it.

Despite efforts to combat what free trade skeptics saw as dubious historical reasoning, Cordell Hull’s narratives about protectionism, war, and peace began to take hold. This paralleled his rising celebrity, having been awarded the Noble Peace Prize in 1945 and publishing his widely-read memoirs in 1948. In 1949, one Senate speech referenced “The high tariff policy of the Smoot-Hawley period, with the consequent destructive retaliatory tariffs against American trade, contributed to the great depression after the First World War [sic].” The next year, a senator remarked that the “Smoot-Hawley tariff is economic isolationism. Economic isolationism will jeopardize peace in the world today just as much as will political isolationism.” After he died in 1955, Hull reached further heroic status, with one senator stating in 1958 that “it took a Cordell Hull to undo the Smoot-Hawley fiasco” and others praising his tireless efforts to promote free trade.

Neoliberalism and the emergence of Smoot-Hawley’s mythological status

From the 1940s to and 70s, we can clearly see that trade policy debates were continuously framed in the terms of the past—specifically the Smoot-Hawley Tariff. The words “return” and “back” accompany references to the tariff dozens of times. Implicitly, liberalization was progress, while protection was regression. However, for much of this time period, the United States enjoyed a considerable trade surplus, meaning that open trade could be sold in both benevolent and self-interested terms. Additionally, many senators still had a living memory of the interwar period and seemingly debated the meaning of the tariff earnestly through both the “contest of analogy” and the “contest of memory.”

From the 1980s onward, the United States entered a new era in both economic policy and historical memory, transforming how the Smoot-Hawley Tariff was employed. After the “Volcker Shock” raised U.S. interest rates and the value of the U.S. dollar, the United States began to run a consistent trade deficit for the rest of the decade. At the same time, the number of Americans (including politicians) with a direct memory of the interwar period faded. Accordingly, there was then both a political-economic need as well as a historical opening for the contested memory of Smoot-Hawley to solidify as a hegemonic and mythologized “lesson” in popular and political culture.

Significantly, Smoot-Hawley was referenced more in Senate debates in the 1980s than in any other postwar decade. It is also at this time that the historical causality ascribed to it grew increasing tenuous, with many senators claiming it led directly to global depression and conflict. One even argued that “Auschwitz and Hiroshima were ultimately consequences of Smoot-Hawley.” In a vain effort to contradict these arguments, Senator John Heinz of Pennsylvania had an entire academic paper entered into the record which attacked the “The Myth of Smoot-Hawley” and downplayed the economic and political effects of the tariff. Still, the belief that Smoot-Hawley led directly to the Great Depression was now fully mainstream in most debates. This argument was echoed at the presidential level in Ronald Reagan’s second term, with him remarking in 1986 that “we learned the lesson [of protectionism] half a century ago when we tried to balance the trade deficit by erecting a tariff wall…the Smoot-Hawley Tariff ignited an international trade war and helped sink our country into the Great Depression.”

When deindustrialization began to accelerate in the late 1980s, trade liberalization was framed in the language of discipline and avoiding the “temptation” of a return to interwar policies. Reagan was the first modern American president to describe protectionism in this way in a 1988 speech to Congress, encouraging the United States to “resist the siren song of protectionism.” In a speech to the U.S. public later that year, Reagan imbued free trade with the gravity of American tradition, arguing that ever since Smoot-Hawley, “the American people have stayed true to our heritage by rejecting the siren song of protectionism.” Continuing this example, in 1992, George H.W. Bush promised he would avoid “quick fixes” and the “siren song of protectionism,” denouncing those “on the right and left [who] are working right now to breathe life into those old flat-Earth theories of protectionism, of isolationism.” Controversially continuing his predecessor’s support for the passage of NAFTA in 1993, Bill Clinton repeated the cautionary tale of when the United States “succumbed to the siren’s song of protectionism” in the interwar period. Signing the trade pact was the only way to avoid this fate, he argued. Maintaining this rhetorical thread in the middle of the turbulence of the global financial crisis, George W. Bush similarly urged the United States to “reject the temptation of protectionism.”

Although initially criticized as protectionist, Barack Obama would also eventually denounce trade barriers by referring to this memory of Depression-era economics. Although both the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TTP) and Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) eventually stalled, he expended significant political capital by pursuing both during his presidency. Wary of the tide turning against free trade toward the end of his second term, in an invited commentary in the Economist, he described what he viewed as the necessary policies to carry the United States into the future. The “way forward,” he argued, was broadly similar to the way of the past seven decades. He advised his potential successors to heed the anti-protectionist warnings of his predecessors, stressing that “we have a choice—retreat into old, closed-off economies or press forward.”

The future of the history of U.S. trade policy

Although dissatisfaction with the international trading order has been apparent for some time, Trump’s shocking 2016 run for the White House—and Bernie Sanders’ surprisingly strong bid for the Democratic nomination—showed that such views could no longer be sidelined from the mainstream of U.S. policymaking. However, the elite outcry over Trump’s 2018 steel and aluminum tariffs—with references to Smoot-Hawley period used frequently to criticize them—showed that a new consensus had yet to take the place of the old liberalizing one. The absence of a clear historical reference point for Trump’s first-term trade policies both reflected and resulted in the lack of a coherent agenda, such as abandoned promises to withdraw from NAFTA.

President Joe Biden’s approach to trade sought to both harness this dissatisfaction with the previous regime and also chart a new, more progressive, policy course. To this end, his USTR explicitly historicized his predecessor’s break with the old consensus, arguing that “Trump’s actions were not an idiosyncratic break with the past, but rather the manifestation of a much deeper paradigm shift.” Instead of the forty-fifth president’s combative approach to trade, however, Biden’s team sought a more coherent and conciliatory approach that did not alienate U.S. allies, even as it kept many of Trump’s policies intact.

One element of this “worker-centered trade policy” was a callback to what the USTR saw as the true legacy of the New Deal, namely the idea that current policymakers could “take inspiration from the vision” of the ITO and its proposal to create “rules that promoted inclusive prosperity and fair competition.” Despite an extensive effort to promote this vision, the new guard at the USTR struggled to assert itself against the preexisting institutional culture and competing priorities in the rest of the administration. For example, National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan recently invoked the traditional warning of a “return to the protectionist and nationalist mistakes of the 1930s,” even as USTR was attempting to move beyond this standard (and in their perception outdated) historical narrative.

Trump’s invocation of McKinley’s tariffs as an example of successful trade policy must therefore been seen in the light of these past “memory battles”—including both the long process through which the dominant narrative of Smoot-Hawley was popularized and the Biden USTR’s recent efforts to replace it with their own historical reference of choice.

In some ways, the incoming administration seems to grasp the monumental nature of this task. Rather than reclaim the “true” legacy of the New Deal order, as Biden’s USTR has attempted to do by resurrecting the values and ambitions behind the ITO, Trump and members of his future administration have taken aim at the entire narrative of postwar U.S. hegemony—contesting the core historical basis of U.S. foreign policy. In his MSG speech, for example, Lutnick espoused an argument that could be considered blasphemy in much of Washington—criticizing post-World War II U.S. efforts to rebuild Europe, lamenting that the United States removed protective barriers throughout the late twentieth century and suggesting that the United States should have ended a conciliatory policy to its allies decades ago. Whether Trump’s split from European allies will be as radical as his administration’s departure from conventional postwar history remains to be seen. One thing is sure, however: regardless of the future of U.S. trade policy, the basis of it will not only be determined in the Oval Office, negotiating table, or halls of the WTO—but also in the memories and analogies that are used to legitimate it.

Supported by the DAAD with funds from the Federal Foreign Office (FF).