Buffalo: The Past, Present, & Future

Astrid Schmidt-King

Loyola University Maryland

Astrid Schmidt-King is a Teaching Assistant Professor at the Sellinger School of Business at Loyola University Maryland, where she teaches various classes in international business (IB), sustainability management, and law and social responsibility. During her time at Loyola, she directed the IB program, served as the director of the honors program and chaired the Building a Better World Through Business initiative. Prior to academia, Ms. Schmidt-King practiced immigration law in New York and Washington, DC. In addition to her BA, JD, and LLM, Astrid completed a hybrid MA from Freie Universität Berlin, where she examined globalization’s socioeconomic impact on developed democracies. She authored a chapter, “Foreign Law and Policy,” in Law and Public Policy, participated in a Fulbright International Education Administrators Seminar (Germany) and the American Council on Germany’s immigration delegation in Berlin, was named a Presidential Fellow by the Association of International Education Administrators, completed the Emerging and Developing Global Executive fellowship by the World Trade Center Institute, and is currently part of the Global Diplomacy Lab.

Julia Sattler

TU Dortmund

Julia Sattler studied English and American studies as well as protestant theology in her native Germany and at Hamilton College, New York. She is currently interim professor of American Studies at TU Dortmund University, where she teaches classes on a variety of subjects relating to nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first century American literature and culture, often with a transatlantic focus. Her ongoing research investigates the narration of urban transformation processes in the German and American Rust Belts from an interdisciplinary angle. Following this trajectory, Julia Sattler is currently studying the negotiation of radical urban transformation processes in U.S.-American poetry.

Shifting Divisions & Reasons to Billieve*

In June of 2022, a group of German and American participants from AGI’ss Social Divisions and Questions of Identity in Germany and the United States Program, gathered in Buffalo, New York, to learn more about the city’s challenges and the strategies developed to respond to its changing post-industrial landscape. Having met in Dortmund, Buffalo’s German sister city, in March 2022, the group had already begun to explore the transformative realities that are unique to post-industrial mid-size cities. In continuing to learn about impediments, progress, and innovative solutions in these cities and the ways cities are transforming, the AGI participants spent five days in Buffalo engaging with the city and its people in various ways: touring its sights and some critical development projects, meeting activists, learning from researchers, and engaging with city officials.

The Past: Shifting Landscapes

The second largest city in the State of New York, Buffalo has been, and continues to be, defined by various landscapes, including geographic and (post)industrial. During the industrial era, Buffalo’s railroads and waterways supported the region’s vibrant trade which was fueled by steel manufacturing, grain milling, and silo storage. However, following World War II, the demand for steel decreased, the accessibility for cheaper products increased, and new competing waterways, including the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1959, all adversely contributed to Buffalo’s economic downturn. “Buffalo starts as basically a seaport […]. Shipping was so incredibly important. […] You take that away, and things are going to decline pretty quickly.” With the loss of manufacturing, including the historic closing of the iconic Bethlehem Steel, came a loss of jobs and economic opportunity. “[T]he steel mills essentially disappeared from Buffalo and its fellow rust-belt neighbors like Pittsburgh and Cleveland […] [A] place where industry used to thrive is now home to just a few industrial plants like Honeywell and General Mills.” This shift demanded that people construct a future that was decidedly different from the past, and it brought with it a multiplicity of challenges including, but not limited to, how to generate new job opportunities, how to find new ways of living in and talking about postindustrial Buffalo, and what to do with abandoned industrial sites.

The Present: Existing Divisions and New Arrivals

The impact of the changing dynamics is reflected in Buffalo’s decreased population—in 1940, the population was 575,901, compared to 276,807 in July 2021. And at the foundation of this population are Indigenous people. “The Buffalo Niagara metropolitan region is considered one of the top 15 major metropolitan areas for Native populations.” In his presentation, Pete Hill from the Native American Community Services of Erie and Niagara Counties introduced us to traditional Indigenous cultures and wisdoms, and he also explained the impact of the historical trauma, which manifests itself in contemporary challenges including disparities in health, education, employment and the economic and social well-being of Indigenous communities. “The history of genocide, forced migration, and broken political treaties […] continues to affect Native communities in Western New York.”

In addition to this division is the stark racial divide that exists in Buffalo. A product of redlining and disinvestment, Buffalo suffers from persistent segregation acutely felt in East Buffalo, the most economically impoverished and marginalized section of the city. The East Side includes the zip code 14208, where on May 14, 2022—only a few weeks before the AGI trip to Buffalo—the racially-motivated massacre at Tops Friendly Market took place. A closely knit community, as described by Devon Patterson at Open Buffalo, the statistics for 14208, an area that is 78.4 percent Black, highlight the lived impact of racism and segregation—the unemployment rate is above the state average, the median household income is significantly below the state average, and the median house value is significantly below the state average. “The East Side, where the Black population here has concentrated for more than 70 years, is hemmed in by Main Street to the west and Eggert Road to the east. Route 33 cuts a gnarly gash between the two. The effect is a community stuck in what locals describe as a cycle of poverty and neglect.”

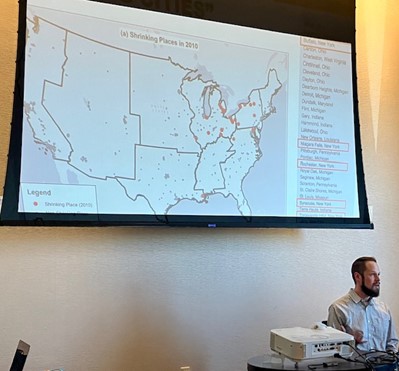

The city’s population loss has exacerbated divisions. A declining population results in decreased tax revenue and public services, contributing to urban flight and concentrated poverty. Russell Weaver, Director of Research at the ILR Buffalo Co-lab Cornell University, explained the importance of engaging communities as sources of solutions. There is a tendency to look externally for answers, investments, new businesses and developments, and new residents to increase the population. This ‘low road development’ often dismisses the critical importance of internal development—‘high road development’—which focuses on enhancing the quality of life for the current residents, turning to them to identify problems and local solutions. Not only is this a human and economic development strategy, but it also responds to addressing the deep divisions in Buffalo.

At the same time, new populations are coming to Buffalo. This is specifically true for refugees and immigrants who are arriving from several African and Asian countries and more recently also, for example, from Ukraine. The resettlement agency Journey’s End addresses the concerns of these new populations, supporting their search for accommodation and access to education, with the long-term goal of leading to economic self-sufficiency of all new community members. To reach this purpose and achieve full-scale inclusion in Buffalo’s society, the organization offers opportunities such as language training and job placement. The future of the city depends on these new arrivals and their full-scale inclusion in many ways: How successfully immigrants can contribute to the city’s economy is evident in the success of the West Side Bazaar, a growing business incubator with clients from many different national backgrounds. At the same time, it is a difficult undertaking to support new populations making their home in an already divided city.

The Future: Shared Connections & Reasons for Optimism

While the divisions run deep in Buffalo, so does the city’s profound pride for a better tomorrow. A city with an underdog mentality, its residents and businesses are resilient, perceptive, adaptive, and innovative. From the ubiquitous Buffalo Bills signs throughout the city, to the profound work of Open Buffalo to advance equity and justice, to the above-mentioned small business incubator WEDI and its mission to “tackle systemic inequities that affect Buffalo’s underserved residents,” the collective community’s commitment toward betterment and development is palpable.[1] As noted by a Bills fan, “We’re a city of enduring people, no matter what odds are against us. As long as we’re living and breathing, we’re still Billieving in Buffalo!”

The Local is Global: Why what happens in Buffalo and Dortmund Matters Globally

Many of the challenges that affect Buffalo can also be observed elsewhere in the Rust Belt, and in other parts of the world where industry historically shaped the economy as well as the culture and local identity. Dortmund, Buffalo’s sister city in Germany, has had its own share of challenges related to de-industrialization, as have former industrial cities across Europe and the United States. Dortmund and Buffalo have developed strategies to respond to ensuing issues including population decline, loss of jobs, and the new post-industrial landscape and identity.

Generally, successful approaches to urban transformation to the post-industrial age include the meaningful integration of the local population and crafting programs, policies, and opportunities that respond to their needs. These certainly include workforce development and employment opportunities, but these efforts also go beyond economic measures alone; efforts at urban transformation need to consider that people will still want to feel at home in their city. In Dortmund, strategies such as the conversion of former industrial sites into museums, art galleries, or other kinds of cultural spaces have been useful to keep businesses around and to attract tourists and even new citizens to the region. In Buffalo, some similar projects are currently underway. But even if a project looks almost the same on the outside—such as the concept to turn Buffalo’s Silo City into a vivid space again via the conversion of the structures into apartments and ‘creative’ spaces—it is important to note that such a project will likely only ‘work’ if it is open to the locals, speaks to their ideas about what the city should be, and pays tribute to its past.

The challenges faced by Dortmund and Buffalo are not simply local in nature. Locally, nationally, and globally it does matter whether communities such as Dortmund or Buffalo thrive, whether they are inclusive settings for their diverse populations, and whether, despite differences, the diverse populations can productively and peacefully live together and support one another. “When social divisions are allowed to fester, they may threaten a country’s underlying social and political stability”—a point to be considered well beyond the local level.

*A term related to Buffalo’s beloved football team, the Bills, a unifier is a very divided city.