Rasande Tyskar via Flickr

#BlackLivesMatter: Social Unsettlement and Intersectional Justice in Pandemic Times

Maureen Maisha Auma

University for Applied Sciences, Magdeburg-Stendal

Prof. Dr. Maureen Maisha Auma is an Educator, Gender Studies Scholar, and Activist. She is Professor for Childhood and Difference (Diversity Studies) at the University for Applied Sciences, Magdeburg-Stendal, since April 2008. She was a Visiting Professor at the Centre for Transdisciplinary Gender Studies and the Institute of Education at the Humboldt University Berlin from 2014 to 2019. She is currently a Visiting Professor at the Centre for Interdisciplinary Gender Studies of the Technical University Berlin. Maisha has been active in the Black queer-feminist collective “Generation Adefra, Black Women in Germany” since 1993. Her research focuses on: diversity, inequality, and plurality in textbooks and didactical materials in East and West Germany, intersectional sexual education as empowerment for Black communities and communities of color, critical whiteness, intersectionality, decoloniality, and critical race theory. Together with Peggy Piesche and Katja Kinder she carried out a consultation process in cooperation with the LADS, the State Agency for Equal Treatment and Against Discrimination for the State of Berlin in 2018. The project was entitled: „Making Visible the Discrimination and Social Resilience of People of African Heritage in Berlin.“ s It was a project within BLACK BERLIN, the UN-Decade for People of African Heritage 2015 - 2024.

Notes From Black Berlin in the Summer of 2020

Seven years after the initiation of the #BlackLivesMatter Movement by Alicia Garza, Patrisse Khan-Cullors, and Opal Tometi, we are again facing a new moment of intense multilayered crisis. This time in a more immediate way, in a connected manner, in real time. The COVID-19 global health crisis has forged a substantial global commonality in less than a half a year. One which had until now, proved elusive. Multiple social movements had tried again and again to initiate this transnational level of shared aims and had consequently failed to achieve it. The convergence of a highly contagious “travelling virus,” relentless social media activism, the hypervisibility of a global death count, the beginning collapse of populist feel-good-political-economies, and the breakthrough of the #BlackLivesMatter activist philosophy has effectively set the stage for a form of transnational unsettlement, whose trajectory we are yet to witness.

From Minneapolis to Berlin

The killing of 46-year-old Georg Floyd, on Monday, May 25, 2020, in Minneapolis, Minnesota sent intense shockwaves across the globe. Mr. Floyd died following the excessive use of force, which is normalized daily, as an appropriate form of interaction with Black bodies in public spaces. A 44-year-old white police officer kneeled for 8 minutes and 46 seconds on Mr. Floyd’s neck, as his life left his body. Seventeen-year-old Darnella Frazier was a witness to this killing. She filmed and then published her video on social media. Her video went viral. Ms. Frazier thus had created an immediacy through her actions, which had the rest of us practically watching Mr. Floyd dying, under the knee of said police officer, almost in real time, all the while hoping for a different outcome, despite the knowledge of the deadly ending. We witnessed the horror of Mr. Floyd calling for his dead mother. We witnessed Mr. Floyd mobilizing the #ICantBreathe articulation, connecting his death directly to the public choking of Eric Garner in July of 2014. The protests which followed this very publicized killing drew on the framework of the #BlackLivesMatter networks to mourn collectively and to publicize the unnecessary loss of Mr. Floyd’s life and the lives of countless other Americans of African heritage at the hands of the daily over-policing of Black bodies (more recently Elijah McClain, Breonna Taylor, Philando Castile, Atatiana Jefferson, and many, many more).

Mourning the Continuous Disregard for Black Lives in Berlin, Leipzig, Stuttgart, Hamburg, Munich, Cologne, Dresden, Bremen, Mainz …

The wave of transnational solidarity amid marches for the “Equal Safety and Equal Protection of Black Lives” resonated very strongly with ongoing activism against the normalization of institutionalized Anti-Blackness, in Germany in general and in Berlin in particular. The symbolism of this transnational moment has resonated artistically and has also translated into forms of collective action and discourse. Afro-Caribbean graffiti artist Jesus Cruz Artiles, also known as EME Freethinker, painted George Floyd’s portrait on a remnant of the Berlin Wall in Mauerpark shortly after the publicization of his killing. While it remains to be seen how the popularization and the mainstreaming of the #BlackLivesMatter theme will translate into policy, initiatives and movements working toward intersectional justice in Germany are engaging actively with #BLM as a traveling concept.

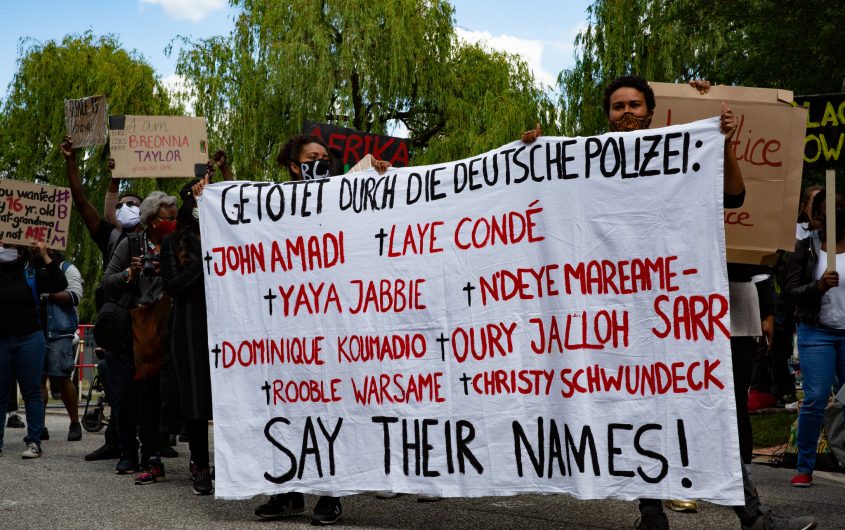

The #BlackLivesMatter Berlin chapter has held annual marches since 2015. Following Mr. Floyd’s killing, #BlackLivesMatter protests erupted in over twenty German cities. #BlackLivesMatter activism in Germany is rooted in struggles against the normalization of racial profiling, institutionalized racism, and racially motivated hate crimes and murders. Racially marginalized groups are at the core of these struggles against their continued dehumanization, at the hands of white-centric institutions and against the assumed disposability of their lives. Racially marginalized collectives assume leadership positions in documenting and publicizing the over-policing and/or racist murders of Sinti and Roma communities, of people who are perceived as Muslim or are socialized as Muslims or practice Islam, of Jewish communities, of people of African heritage, and of Trans* and Inter people (all named as formally recognized vulnerable groups in the National Plan of Action Against Racism of 2017).

German institutions have tried and failed again and again to hold their employees accountable for police killings of racially marginalized groups, for neglectful behavior which has resulted in unnecessary deaths, or for inept investigations against white supremacist (mass-) murderers. The #BlackLivesMatter movement has now provided a powerful symbol, a recognition discourse, and a politicized framework to more effectively publicize institutionalized Anti-Blackness and its fatal effects. It has also provided a space for solidarity work among those racially marginalized groups, whose work is intersectional and thus geared toward transformative justice. In the light of #BlackLivesMatter, the killings of Mariame N‘Deye Sarr (26 years old, 2001), Dominique Koumadio (23 years old, 2006), Oury Jalloh (37 years old, 2005), Christy Schwundeck (40 years old, 2011), William Tonou-Mbobda (34 years old, 2019), and many, many others, have been contextualized within the frame of pervasive institutionalized Anti-Blackness. The social media movements #SayTheirNames and the intersectional version #SayHerName, both inspired by #BLM, have also found resonance in Germany. The racist (white supremacist) mass killings/shootings of the NSU-Komplex, a self-named undercover national socialist cell (2000 – 2007), and the attacks in Halle (2019) and Hanau (February 2020) are in this vein interconnected; they are effects and materializations of institutionalized negligence toward the lives of racially marginalized communities. A recent initiative #SayTheirNamesGermany has mobilized social media using their campaigns to empathetically humanize the nine citizens of Hanau, the Sinti and Roma, Kurdish, and other people of color who lost their lives in a shisha bar on February 19, 2020. Their names are: Mercedes Kierpacz, Vili Viorel Păun, Ferhat Unvar, Gökhan Gültekin, Hamza Kurtović, Sedat Gürbüz, Kaloyan Velkov, Fatih Saraçoğlu, and Said Nessar Hashemi.

Essential Work and the Effects of Racially Motivated Dismantling of Health Protections

When 50-year-old Black transit worker Jason Hargrove, a bus driver in Detroit, died of COVID-19 only eleven days after publishing an angry indictment of missing protections and inconsiderate riders on social media, the grief over his loss was intense and boundless. It resonated across borders. It brought home the disproportionate cost of the work executed daily by cleaners, meat packers, farmworkers—people whom we depend on for our lives and livelihoods, but whose work is consistently undervalued. People who are forced to return to work in unsafe conditions. People who, due to institutionalized racism, belong disproportionately to racially marginalized groups.

On a very personal note: Not for the first time, but in its intensity unprecedented, I have thought about the mostly Black and migrant cleaning crews in German universities and other public institutions. I see and interact with them every day, either very early or very late in the day. They are otherwise nearly invisible. They cannot work from their home offices. They were out there on the frontlines every day during the lockdown, ensuring that the supermarkets in which we shop are cleaned, the hospitals are cleaned, the buses, streets, and subways are cleaned. Their essential work is neither recognized nor rewarded with a bonus. Their high risk of exposure and infection is not publicized. At a time in mid-March, when I still wiped clean all my groceries because it was not yet clear how the virus could or could not be transmitted, at this time cleaning crews were our shield against the chaos, against the virus. We do not pay these essential workers a fair wage. We have normalized an exploitative situation in which they live with high risks while at the same time managing very limited choices.

The French strike-collective “Frotter, frotter, il faut payer” (We scrub, we scrub, you pay!) is a recent example for the intersectional struggle for economic justice and for the redistribution of economic power. Its members are mostly working-class Black women—hotel workers—many of them immigrants. This collective scandalizes their exploitation and exclusion, as they enable the daily function of luxury hotels, at the expense of their health and the wellbeing of their families. Their movement has yet to be self-televised.

2020 is the halfway mark of the UN Decade for People of African Heritage (2015 – 2024). Berlin is the only federal state that anchored the implementation of the Decade in its Coalition Treaty of 2016 for the current legislative period (2016-2021). A complaint against the violation of George Floyd’s human rights has been submitted in the frame of this decade. Similar intersectional work is underway in Berlin. In the absence of an effective infrastructure (commissions for the analysis of anti-Blackness in particular and racism in general), in the absence of intersectional Black studies, it is again BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People-of-Color) people who are stepping into the gap, pushing for recognition and for social and political inclusion. #BlackLivesMatter has become a powerful reference for the recognition of the fatal toll of racialized dehumanization, crucial to the work of these collectives. The trajectory of its mainstreaming in Germany remains to be seen.