Swedish Presidency of the Council of the EU via Flickr

Transatlantic Cooperation vs. Tech Nationalism

Andreas Freytag

Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena

Dr. Andreas Freytag is Professor of Economics at the Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena, Honorary Professor at the University of Stellenbosch, and Visiting Professor at the Institute of International Trade, University of Adelaide. He is also Director of G20 Trade and Investment Research Network. He is a DAAD/AGI Research Fellow in October and November 2023.

Dr. Freytag obtained his diploma from the University of Kiel and his doctorate as well as his Habilitation from the University of Cologne. He has published a number of books and articles in first-class peer-reviewed journals on economic policy, international trade policy, development economics, and international policy coordination. He contributes to blogs and for over ten years had a weekly column on wiwo-online, a German magazine.

During his time at the AGI, Andreas Freytag will focus on the substance and path of tightened transatlantic relations against the background of the systemic competition between the West and autocratic states. The latter comprise some emerging economies, including Russia and China. This escalation has geo-political and geo-economic consequences and makes it necessary to strengthen the ties between transatlantic partners as well as to reach out jointly to attract third countries to the Western values.

To maintain Western leadership in standard-setting as well as helping developing countries to enforce universal human rights and environmental standards, there needs to be a coordinated and broad-based strategy to (1) react to Chinese et al. attempts to define and set standards, which become binding for third countries’ companies. Similarly, (2) due diligence legislation may also be more effective if coordinated across the Atlantic. Although not in the center of analysis, another (3) aspect deals with the transatlantic trade relations as such, which are also in need of a revitalization.

This project focuses on the geo-economic aspects of systems competition although it is difficult to disentangle economic and political relations. It analyzes ways to intensify the transatlantic relations with the objective to maintain economic welfare as well as to position the Western partners better to counter autocracies’ attempts to gain influence in the world economy.

Values and Standards in the New Systemic Competition

It is widely accepted that the ability to set technological standards is a prerequisite for an economy’s success on the world markets; this holds especially for digital technologies. At the same time, to reap maximal benefits, it is important that a standard is widely accepted and used. Global cooperation is ideal. In early November 2023, the world witnessed an artificial intelligence (AI) summit convened in North London at the invitation of the British government. The result was an agreement between the United States, the European Union, China, other countries, and leading companies to work out a regular framework for AI standards.

This is good news in a global policy climate characterized by a number of geopolitical and geoeconomic problems. Next to political conflicts that have the potential to develop into a cold war with some hot excesses, there are challenges such as digital transformation, climate change, and security. The agreement in London on AI is a promising signal, but at the same time, it does not indicate that China or Russia will cooperate on AI without second thoughts.

These challenges put domestic governments across the Atlantic in an awkward position. They require that states both ensure access to critical resources and protect domestic high-tech businesses as well as maintain a high living standard for their citizens. Under the current situation of distrust and systemic rivalry, a rising tendency toward tech nationalism, even in the relation of close partners, evolves. In the United States, there is an established bipartisan taste for protectionism and subsidies to manage contemporary challenges. Similar trends can be seen in Europe, both at the EU level and in national politics. In Germany for instance, the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Action has been trying to introduce an industrial policy based on subsidies for politically warranted sectors and technologies.

History shows that subsidy races and protectionist isolationism cause inefficiencies on both sides of the Atlantic. This is particularly relevant against the background of systemic competition between the West on the one hand and China and other autocracies on the other hand. From a geopolitical perspective, it is thus necessary to cooperate across the Atlantic. There are viable alternatives to protectionist and nationalist impulses, the most viable being intense competition in markets in an atmosphere of regulatory cooperation.[1] The benefits of transatlantic economic relations go beyond static gains from trade and include the ability to generate product and process standards based on a joint set of values, as this enables the partners to gain traction in geopolitics.[2] Given the high complexity and the enormous challenges in the new systemic competition, this perspective on transatlantic relations is of the utmost importance.

If the transatlantic partners manage to create and enforce joint high standards, both with respect to technical and environmental regulations as well as social aspects of trade and investment, they might not only improve the well-being of their citizens but also be able to attract businesses from other countries. The standards might also generate interest in these countries to get better acquainted with Western values, which again is a step to secure the global Westphalian liberal order.[3]

This essay develops the argument that transatlantic relations should be further (officially) intensified to gain traction in the ever more intensive systemic competition—or rivalry—between the West and some autocratic countries, first and foremost China. Based on similar values, maintaining leverage in standard-setting approaches is an instrument to secure economic prosperity across the Atlantic and at the same time make the transatlantic market attractive for companies from third countries.

The political economy of regulations and standards

For an economy to work, regulations and standards are critical. Depending on the complexity and the efficiency of market forces, these regulations range from general rules of conduct on markets, e.g., in the commercial code, to explicit regulations of specific markets because of market failures, e.g., in a telecommunication law.[4] In a similar vein, standards are necessary to make markets work. They allow technological solutions to be compatible with each other and thus reduce transaction costs. The more open a standard is, the easier firms can connect to it and the larger the benefits are; network externalities exist and grow. Complex patent structures and political or security considerations may reduce this openness or demand disclosure of connecting firms’ technologies, which reduces the potential benefits. Similarly, standards also lock in certain technological solutions and thereby create path dependencies.[5] This ambiguity suggests that firms invest much into the standard-setting process and try to make their own technological solutions binding for the whole industry. In addition, standards are rules in a very dynamic market; they are permanently subject to change.

In practice, standards have mostly been set by private actors who organize themselves in so-called Standard-Setting Organizations (SSOs). The process itself is dynamic and depends on the distribution of power between the involved actors as well as the institutional settings that differ between countries. States often enter the process very late or just accept the results. Since standards very likely create path dependencies and network externalities, the process of standard setting has always been characterized by power games. [6]

The United States should intensify the cooperation in standard setting across the Atlantic, using as open as possible standards, so that other countries can adapt the standards and the network externalities can be maximized.

The literature on standards also mirrors different perceptions of this subject across the Atlantic. In Europe, the state plays a larger role as regulator, standard setter, and even entrepreneur. On the same token, when it comes to digital trade, the topic of data protection is weighted much higher than the opportunities of less regulated trade. The EU’s market size allows it to impose regulations and standards like data protection to other countries. This is called the Brussels effect.[7] In the United States, a similar effect is assigned to standard setting in a private, partly competitive process, leading to the highest possible standards—a race to the top. This is termed the California effect. The reality disproves a widespread fear of civil society—particularly in Europe—that global private competition leads to a race to the bottom, the so-called Delaware effect.

Oliver Williamson’s four layers of institutions[8] in a society can explain the role of standards and their relation to the value system.[9] The first layer comprises those institutions, such as religious or cultural values, which are long-lasting and change only slowly—within centuries—and mostly spontaneously. A basic value in one country or continent may not work in another country or continent. The second layer comprises those institutions that change slowly (Williamson speaks of decades) and over time. Examples are some dimensions of gender relations in society, e.g., equal pay for women in the workplace or environmental consciousness. The speed and direction of changes are dependent on the institutions in the first layer. The third layer is short-term. It contains policy measures, which can be taken quickly, but often still need years of preparation and discussion. They again depend on the institutions on the second and first layers respectively. Standards and regulations are part of the third layer. The fourth layer reflects daily life.

It is exactly at this interface between values and standards where the increasingly intense systemic competition within the West and between Western countries and a group of—partly coordinated—autocracies becomes relevant. As the first and second layer of institutions is very similar across the Atlantic, it seems relatively easy to agree on standard setting. However, these Western values are very distinct from, e.g., the Chinese or Russian set of institutions. Nevertheless, the consensus in the West until recently has been that in most countries the desire to share Western values, which indeed are regularly perceived as being universal, is strong. As a consequence, Western countries have begun to ‘export’ their value system to other parts of the world via due-diligence laws and trade agreements with Trade and Sustainable Development (TSD) clauses respectively. Only in the last couple of years, it has started to dawn on Western policymakers, citizens, and businesspeople that not only governments in autocratic or semi-autocratic countries but also citizens there do not appreciate these values. Western behavior is even often perceived as coercive by the trade partners. In addition, they complain about double standards in cases when Western governments enforce legislation more strictly against economically less important countries than against, e.g., China or Vietnam. There is an easier way to attract these countries to universal values—economic integration.

The changing nature of standard setting in systemic competition

In principle, technological standards should be agreed upon by actors from all countries in order to benefit from the widest network externalities and reduce transaction costs for all. However, in the new systemic competition, global cooperation is on the retreat. The struggle for values trickles down to technological standards. Since these often affect social relations, standards may be mutually exclusive between the systemic competitors.

China has quite openly increased its attempts to define new standards for its own businesses as well as potential partners, particularly in IT. Since the early 2000s, China has undertaken various efforts to introduce its own technological standards; a very prominent case being its Wireless LAN Authentication and Privacy Infrastructure (WAPI), which was meant to be an alternative to WiFi.[10] This standard was constructed to be exclusive and closed. Only a handful of Chinese companies got access to the encryption algorithm; all other firms had to connect and thereby publish their technical specifications. This was not only an offense toward Western competitors but also violated the national treatment principle of the World Trade Organization (WTO). The attempt finally failed because of the resistance of the United States and the WAPI’s inability to outperform WiFi. The case shows the relevance of standard-setting potential for a nation. It also shows how important the openness of a standard is. The Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) can also be interpreted as another step in that direction.

If the transatlantic partners cooperate in high-tech standard setting rather than engage in tech nationalism, one can expect both a race to the top (the California effect) and a critical mass (the Brussels effect).

The United States has intensified its responses since the WAPI case and now tries to cut off China from the latest technologies, particularly in digital tech. However, this may be a questionable strategy. By doing so, the Chinese government might be forced to develop its own standards. This time, the success may be greater than in the WAPI case, leading to two parallel standards in certain applications. This is increasing transaction costs globally. It might also lead to transatlantic tensions. Therefore, the United States should choose an alternative path, namely to intensify the cooperation in standard setting across the Atlantic, using as open as possible standards, so that other countries can adapt the standards (the Brussels effect) and the network externalities can be maximized. At the same time, this process will very likely lead to better standards (the California effect).

The need for more effective transatlantic cooperation in standard setting

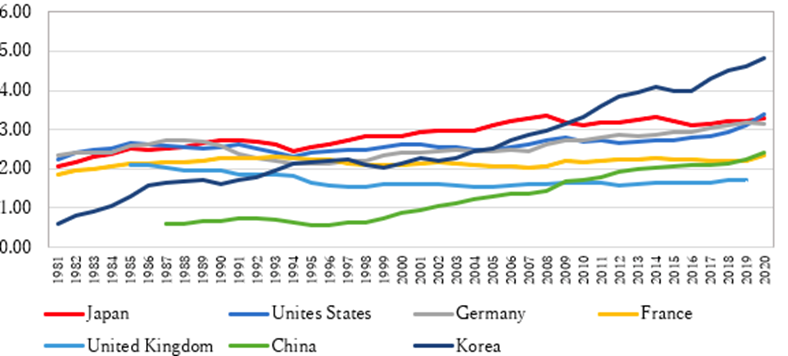

The United States and the EU are still global tech leaders, but the position is contested. Whereas in 2006 some 80 percent of global standards were set by EU or U.S.-based actors,[11] the situation has since changed. Ever more Chinese companies successfully apply for patents internationally and are able to set standards. R&D spending in China increased massively in the last thirty-five years, only matched by South Korea (Figure 1).

Figure 1: R&D expenditure as share of GDP

Source: Japanese Center for Economic Research

This has not gone unnoticed. Both the United States and the EU have developed strategies to maintain technological leadership. This happened partly in tight cooperation, using the EU-U.S. Trade and Technology Council (TTC), e.g., in the case of electric vehicle charging and AI.[12] However, both partners also operate individually, with concepts that often seem to be directed against each other rather than to better position transatlantic economies in the systemic competition outlined above as two examples show:

- The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) is a subsidy program (using grants, tax incentives, and loans up to 369 billion U.S. dollars) for firms investing in energy security, climate change response, and health projects. Its economic impact is yet unclear not least because, due to domestic content rules, fears have risen that the money will be given exclusively to U.S. firms; foreign investors are afraid to be left out. These fears may seem exaggerated, but there certainly will be political pressure to favor U.S. companies over European competitors.[13]

- Similarly, the European Standardization Strategy of Spring 2022[14] is an attempt to harness the European tradition of bottom-up standards and a top-down approach to identify strategic fields in which European standards are deemed necessary, mainly in the areas of digital transformation and climate protection.[15] This is not seen uncritically in the United States, as the EU uses this strategy to diminish the influence and cooperation of U.S. experts in European telecommunication standard setting. Some observers see it as a sign of growing tech nationalism.[16]

While it seems clear that these strategies and the according critiques are often driven by pressure groups and political influence, there is widespread support in academic and think tank circles for the idea that governments identify critical technologies and protect these areas from foreign influence.[17] This concept regularly attracts attention and generates support in times of crisis. That does not make it a reasonable strategy, as it suffers from four serious shortcomings, as already discussed above:

- National or even EU-wide standards will cause high transaction costs across the Atlantic; network externalities will not be exploited maximally.

- A standard or a technology selected by governments and not detected in international competition may be suffering the well-known problem called ‘pretense of knowledge,’ implying that despite the best of a government’s intentions, it is difficult for a central agency to predict future trends.[18] It is highly doubtful that civil servants have a better feeling for market opportunities than entrepreneurs.

- That also implies that the path dependency problem might be worse than in a private and competitive environment for standard setting.

- Adding to that problem, government leadership will encourage lobbying activities rather than innovation activities.

In sum, statist innovation strategies are unlikely—by default and not because of misbehavior—to guarantee success. These and the institutional economic considerations above rather suggest an intense transatlantic cooperation based on the principles of Western liberalism. This means in particular to allow for competition for standards as well as for goods and services across the Atlantic.

Transatlantic options

As mentioned earlier, the United States and the EU share the same set of values on the first two layers of Wiliamson’s analysis. So it is not by chance that the EU and the United States are by far each other’s most important trading and investment partners.[19] Despite political tensions across the Atlantic during the Trump administration, transatlantic trade and investment has intensified, especially after the pandemic. These private activities should encourage political initiatives that foster transatlantic exchange without either reducing defensive trade instruments or neglecting, even harming, other partners. This effort should learn from the past and at least two past failures.

Transatlantic cooperation in standard setting allows partners to maximize network externalities and enlarge the spectrum of possible solutions.

That said, transatlantic trade initiatives are not new. Already in the mid-1990s, there were transatlantic talks to create a Transatlantic Free Trade Area (TAFTA). They focused on classical trade barriers and were abandoned after a few years. Some twenty years later, the partners attempted to agree on a Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). It included tariffs, non-tariff measures (NTM), and regulations; a concept known as WTO+. The geopolitical potential of TTIP was also seen in the beginning tensions with China in the mid-2010s. Standards and regulations were among the topics that finally rendered TTIP negotiations unsuccessful. In principle, the negotiators could imagine mutual recognition of regulations with a substantial negative list of exemptions.[20] That did not suffice; political resistance in the United States and public resistance in the EU were too high.

Transatlantic cooperation in standard setting is a much less prominent path, with high benefits as discussed above; in the attempts to negotiate TAFTA and TTIP respectively, standard setting was not the focus. There are two possible ways forward.

- In principle, standard setting is mostly organized in private SSOs, which generally function well. In the case of AI, it has been observed that private actors from all over the world, including U.S. and Chinese experts, work closely together in standard setting, whereas governments are reluctant.[21] Therefore, it would probably be sufficient to agree on a negative list of actions—in particular discrimination of the other side’s companies and scientists. With respect to the two examples of perceived tech nationalism, access to IRA should be non-discriminatory, and the EU should not dismiss U.S. expertise in their cyberstrategy. In fields of strategic importance, restrictions will be made anyway, but in other areas, standards should be open.

- With the TTC, both partners have an instrument which can be used to increase transatlantic leverage in high-tech industries. It was established in 2021 on the ministerial level and works within ten working groups, one of which deals with technical standards. One of the objectives is the prevention of new unnecessary technical barriers to trade (TBT).[22] Since its founding, the TTC has organized four ministerial meetings. The pledges to cooperate in AI are remarkable.[23]

It is, however, also clear that the pledges made during summits and ministerial meetings have to be put into political practice. On this count, the progress made in transatlantic economic relations has been modest in the last ten years. Politically, it seems difficult to overcome the stalemate. A pragmatic perspective on the common challenges caused by the new systemic rivalry is definitely needed; although the grand picture and a revitalization of the multilateral order should not be lost, short-term and smaller objectives such as agreeing on terms regarding standard setting would help.[24] If the transatlantic partners cooperate in high-tech standard setting rather than engage in tech nationalism, one can expect both a race to the top (the California effect) and a critical mass (the Brussels effect). As a consequence, producers from other countries are attracted because of the size of the transatlantic marketplace.[25] As long as this strategy does not compromise European and U.S. security needs, it will generate a win-win situation.

Conclusion

The importance of a standard-setting capability for national security and wealth is widely acknowledged in political circles and their academic advisory bodies. However, it is not obvious to these actors to what extent they should rely exclusively on domestic forces to maintain the ability to set world-class standards, which also attract foreign businesses. Due to the multiple crises since the Great Recession starting in 2008, there is a growing tendency to resort to tech nationalism. This is not new, as, in times of crisis, multilateral or plurilateral action is politically unpopular. That said, unilateral actions and economic nationalism rather worsen than improve the situation. The theory of institutions shows that transatlantic cooperation in standard setting allows partners to maximize network externalities and enlarge the spectrum of possible solutions so that the best possible standards—for the time being—can be expected.

Therefore, this essay defines areas where transatlantic cooperation in standard setting is effective, efficient, and serves the security needs of both sides, in particular with respect to autocratic countries. To be precise, it is assumed that most sectors will harness transatlantic competition as well as its diversity to set standards that are technically advanced and in line with Western values (layers one and two of Williamson’s scheme). Such cooperation may attract producers from third countries, as they want to be part of the big transatlantic market. As a side effect, these third countries may be drawn to accept Western values as universal when they see the benefits of integrating closer into the transatlantic marketplace. This is not guaranteed and will not be enforced (or as some may call it: coerced) by the United States and the EU but is it not fully out of range. Both the Brussels and the California effects may be at play.

Both the economic and political potential speak in favor of intensified transatlantic cooperation. In times of urgent challenges—both technological and political—it is irresponsible not to resort to it.

[1] See Björn Fägersten, Ulla Lovcalic, Anna Lundborg Regnér, and Swapnil Vashishtha, “Controlling Critical Technology in an Age of Geoeconomics: Actors, Tools, and Scenarios,” The Swedish Institute of International Affairs (2023).

[2] See Pavlina Pavlova, “Beyond Economics: The Geopolitical Importance of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership,” European View (2015): 209-216; and Robert D. Hornats, “The Geopolitical Implications of TTIP,” in: The Geopolitics of TTIP: Repositioning the Transatlantic Relationship for a Changing World, ed. Daniel S. Hamilton (Washington, DC: Center of Transatlantic Relations, 2014): 13-20.

[3] This is a long-term process with very slow progress, but it may be an alternative to the attempt to impose liberal values on other countries with due-diligence legislation or Trade and Sustainable Development (TSD)-clauses in free-trade-agreements.

[4] Such market failures are (exclusively): externalities, asymmetrical information, and natural monopolies due to indivisibility. See e.g. N Gergory Mankiw, Principles of Economics, 10th edition (Boston: Cengage, 2024).

[5] That said, it is not always the best option for the long term that is chosen; path dependency then prevents a shift to better solutions.

[6] There is a large literature about standard setting in almost all social sciences. One fine late example is JoAnne Yates and Craig N. Murphy, Engineering Rules. Global Standard Setting Since 1880 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019).

[7] See Anu Bradford, The Brussels Effect: How the European Union Rules the World (Oxford University Press, 2020).

[8] Institutions in economic analysis are the rules, norms, and values that drive human interactions. They both evolve spontaneously over time or are created by purpose; they can be formal or informal, i.e., without any written basis. See Douglas C. North, Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

[9] Oliver E. Williamson, “The New Institutional Economics: Taking Stock, Looking Ahead,” Journal of Economic Literature 38, no. 3 (2000): 595-613.

[10] For an analysis of WAPI see Heejin Lee and Sangjo Oh, “A Standards War Waged by a Developing Country: Understanding International Standard Setting from the Actor-Network Perspective,” Journal of Strategic Information Systems 15, no. 3 (2006): 177-195.

[11] Leif Johan Eliasson, “International Standards: Past Free Trade Agreements and the Prospects in the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership,” Baltic Journal of European Studies 5, no. 1 (2015): 5-18.

[12] See the EU-U.S. Joint Statement of the Trade and Technology Council of December 5, 2022: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/statement_22_7516.

[13] Max Gruenig (2023), “One Year Inflation Reduction Act: Initial Outcomes and Impacts for US-EU Trade and Investment,” Konrad Adenauer Foundation in Partnership with E3G (Washington, DC: September 2023).

[14] European Commission, “New approach to enable global leadership of EU standards promoting values and a resilient, green and digital Single Market,” February 2, 2022.

[15] Tim Rühlig, “The Rise of Tech Standards Foreign Policy: Brussels Goes Strategic,” DGAP Online Commentary, February 3, 2022.

[16] Nigel Cory, “How the EU Is Using Technology Standards as a Protectionist Tool in Its Quest for Cybersovereignty,” Information Technology & Innovation Foundation, September 19, 2022.

[17] A recent example is Julian Ringhof, “The Tech Standards that Shape the Future: How Europeans should Respond to China’s Rising Influence,” European Council on Foreign Relations, August 9, 2023.

[18] See the work of Nobel Prize winner Friedrich August von Hayek.

[19] See for the latest figures Daniel S. Hamilton and Joseph P. Quinlan, “The Transatlantic Economy 2023: Annual Survey of Jobs, Trade and Investment between the United States and Europe,” Foreign Policy Institute, Johns Hopkins University SAIS/Transatlantic Leadership Network, 2023.

[20] See the reports by Peter Draper, Andreas Freytag, and Susanne Fricke, “The Impact of TTIP,” “Volume 1: Economic Effects on the Transatlantic Partners, Third Countries and the Global Trade Order” and “Volume 2: Political Consequences for EU Economic Policymaking, Transatlantic Integration, China and the World Trade Order,” Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, September 29. 2014.

[21] Nora von Ingersleben-Seip, “Competition and Cooperation in Artificial intelligence Standard Setting: Explaining Emergent Patterns,” Review of Policy Research 40 (2023): 781-810.

[22] See “U.S.-EU Summit Statement,” The White House, June 15, 2021. As most TBT are unnecessary, this statement is very vague, the partners also do not fully live up to it.

[23] It was made at the third meeting and reiterated at the fourth. See “EU-U.S. Trade and Technology Council: Documents,” European Commission, where the documents of all meetings can be found.

[24] Peter Rashish, “Between Nationalism and Multilateralism: A Renewed Approach for Transatlantic Economic Engagement,” American-German Institute Issue Brief 59, September 9, 2019.

[25] In this context, it may well be noted that these considerations can easily be extended toward other OECD countries with a similar value system such as the UK, Australia, New Zealand, or Japan. A common market for standards comprising these countries will definitely be attractive for third parties.

Supported by the DAAD with funds from the Federal Foreign Office (FF).