Baummapper via Wikimedia Commons

The Anti-Semitism Scandal at Documenta 15

Eric Langenbacher

Senior Fellow; Director, Society, Culture & Politics Program

Dr. Eric Langenbacher is a Senior Fellow and Director of the Society, Culture & Politics Program at AICGS.

Dr. Langenbacher studied in Canada before completing his PhD in Georgetown University’s Government Department in 2002. His research interests include collective memory, political culture, and electoral politics in Germany and Europe. Recent publications include the edited volumes Twilight of the Merkel Era: Power and Politics in Germany after the 2017 Bundestag Election (2019), The Merkel Republic: The 2013 Bundestag Election and its Consequences (2015), Dynamics of Memory and Identity in Contemporary Europe (co-edited with Ruth Wittlinger and Bill Niven, 2013), Power and the Past: Collective Memory and International Relations (co-edited with Yossi Shain, 2010), and From the Bonn to the Berlin Republic: Germany at the Twentieth Anniversary of Unification (co-edited with Jeffrey J. Anderson, 2010). With David Conradt, he is also the author of The German Polity, 10th and 11th edition (2013, 2017).

Dr. Langenbacher remains affiliated with Georgetown University as Teaching Professor and Director of the Honors Program in the Department of Government. He has also taught at George Washington University, Washington College, The University of Navarre, and the Universidad Nacional de General San Martin in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and has given talks across the world. He was selected Faculty Member of the Year by the School of Foreign Service in 2009 and was awarded a Fulbright grant in 1999-2000 and the Hopper Memorial Fellowship at Georgetown in 2000-2001. Since 2005, he has also been Managing Editor of German Politics and Society, which is housed in Georgetown’s BMW Center for German and European Studies. Dr. Langenbacher has also planned and run dozens of short programs for groups from abroad, as well as for the U.S. Departments of State and Defense on a variety of topics pertaining to American and comparative politics, business, culture, and public policy.

__

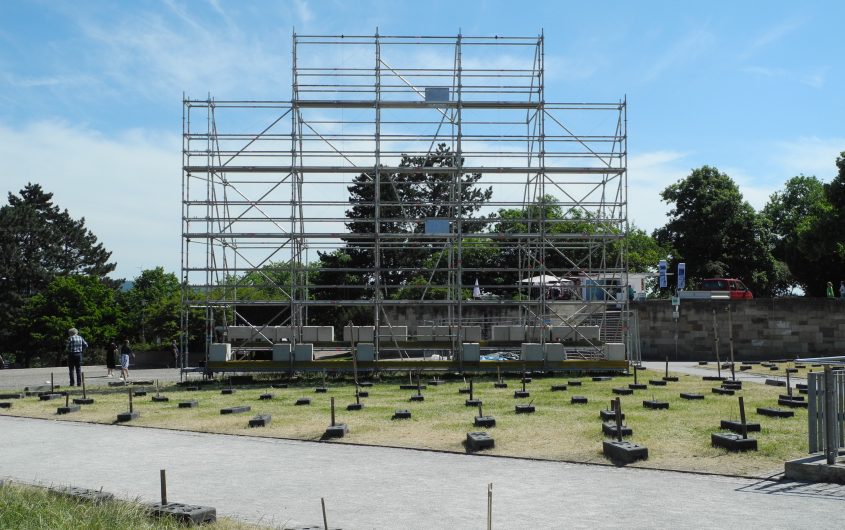

Documenta is one of the highest-profile contemporary art exhibitions in the world. Dating back to 1955, the exhibition runs for several summer months in and around the small central German city of Kassel located in the state of Hesse. About one million visitors are expected this year, all financed by about 42 million euros in public funds. As the official website states, it is: “not only a forum for current trends in contemporary art, but a place where innovative and standards-setting exhibition concepts are trialed…. The discourse and the dynamics of the discussion surrounding each [D]ocumenta reflects and challenges the expectations of society about art.”

There was great anticipation over the fifteenth iteration running from June to September 2022 because for the first time, curation was given to an artistic collective (ruangrupa) from Indonesia. Their vision is based on the “core values and ideas of lumbung (Indonesian term for a communal rice barn). Lumbung as an artistic and economic model is rooted in principles such as collectivity, communal resource sharing, and equal allocation, and is embodied in all parts of the collaboration and the exhibition.” The curatorial group then engaged with a variety of other artists and collectives to bring together over 1,500 artists with the primary purpose of highlighting the global South and persistent challenges with artistic equity vis à vis the global North. The 2022 Documenta exhibits more conventional works of art along with archival projects, gardens, performance art, lectures, and a variety of events.

However, months before the opening in June, controversy began to swirl. Beginning in January 2022, various groups such as the Alliance against Anti-Semitism Kassel accused the organizers of anti-Semitism. Several of the invited artists, deemed “anti-Israeli activists,” had expressed support for the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement, which “works to end international support for Israel’s oppression of Palestinians and pressure Israel to comply with international law.” Hugely controversial, the BDS movement was condemned as anti-Semitic in a formal resolution passed by the German Bundestag in 2019. Some participating artists have characterized Israel as colonial state of white people practicing a form of apartheid. It was also pointed out that no Israeli artists had been invited, yet the Palestinian group The Question of Funding had been. In light of these criticisms, Documenta organizers scheduled, but then postponed, several public discussions in May to address these issues. Ruangrupa responded to the allegations of anti-Semitism with an open letter, stating: “We strongly reject these accusations and refuse to accept bad-faith attempts to delegitimize artists and preventively censor them on the basis of their ethnic heritage and presumed political positions.”

On opening day, June 18, Federal President Frank Walter Steinmeier delivered remarks, noting at the outset that he was hesitant to attend because he was “taken aback by the abrasiveness of this dispute, by the irreconcilability of the tone adopted.” He went on: “I followed the discussion prior to this [D]ocumenta very closely, about what we must expect from art, and also about the, at times, thoughtless and reckless approach to the State of Israel.” Moreover, “When contact to independent minds from Israel is not allowed, when they are excluded from encounters and discourse with a cultural international community that otherwise prides itself on openness and freedom from prejudice, then this is more than mere ignorance. Where this occurs systematically, it is a strategy of marginalisation and stigmatisation that is indistinguishable from hatred of the Jews.”

On the same day as Steinmeier’s speech, a massive banner entitled People’s Justice, created by another Indonesian collective Taring Padi in 2002, was unveiled. The banner—a depiction of Indonesian society under the Suharto dictatorship and its aftermath pitting capitalist oppressors against the people—contains two unequivocally anti-Semitic images—a Mossad agent depicted with a pig’s face and in the background an Orthodox Jewish figure with fangs and “SS” painted on his hat. (More photos available at Deutsche Welle.)

The outcry was immediate. Josef Schuster, President of the Central Council of Jews in Germany wrote, “However, it doesn’t matter where artists who spread anti-Semitism come from. Artistic freedom ends where contempt for humanity (Menschenfeindlichkeit) begins. This red line was crossed at the Documenta. Those responsible for the Documenta must now live up to their social responsibility and draw the necessary conclusions.” Sascha Lobo called the entire exhibition “Antisemita,” also observing a “broad acceptance of anti-Semitism in Germany.” The curators responded by first covering over the banner and then a day later removing it altogether.

Several attempts at explanation and apology made things worse. Taring Padi published a response, stating, in part, “the characters, signs, caricatures, and other visual vocabulary in the works are culture-specifically related to our own experiences…. It is in no way related to anti-Semitism. We are sorry that details of this banner are misunderstood outside of their original purpose. We apologize for the injuries caused in this context.” Several people pointed out that the banner had been previously displayed in Australia and China, with no outcry (which also shows how little awareness there is in many countries about such insidious anti-Semitic imagery). Sabine Schormann, the managing director of Documenta, emphasized that the banner was not commissioned for Kassel but in the context of the political protest movement in Indonesia and concluded, “Everyone involved regrets that feelings were hurt in this way”—note the use of the passive voice.

And the controversies have continued. The head of the German-Israeli Society Volker Beck and others called for Schormann’s dismissal, and Beck has reportedly filed a criminal complaint, given that such anti-Semitic images are illegal in Germany. In an attempt to manage the fallout from the scandal, more dialogues have been proposed, and a consultant from the Anne Frank Educational Center in Frankfurt Meron Mendel was employed to help scrutinize the assembled works of art for any other anti-Semitic images or messages. Just a couple of weeks later, he resigned, citing an almost complete lack of communication and unwillingness to engage from Documenta management, saying that he was being used as a fig leaf (Feigenblatt). Also, in early July, the artist Hito Steyerl withdrew her works from the exhibition, citing both the failure of ruangrupa to monitor artworks for anti-Semitism and the unwillingness of the organizers to actually confront the problem.

There is absolutely no excuse and justification for what happened—especially since alarm bells were ringing for months. There is no cultural context in which such blatantly anti-Semitic images would be acceptable.

On July 6, the Bundestag’s Committee on Culture and Media had an open hearing. All parliamentary groups and Culture Minister Claudia Roth condemned the anti-Semitic images. Roth said that the boundaries of artistic expression were exceeded and that the curators had breached their promise (Wortbruch). Ade Darmawan, a member of ruangrupa, apologized for “causing pain” and claimed that anti-Semitic images were brought to Indonesia by the Dutch colonizers and were passed on especially to the Chinese minority. Whether this is true or not, it is problematic for him to pin this on the Chinese minority, given how often then have been violently targeted, including in 1998 when the Suharto regime collapsed. He also noted that there were indeed Israeli and Jewish artists involved in Documenta, but that they did not want to be identified. He also said that he does not support the BDS movement and “does not support Israel’s isolation.” Daniel Botmann, the managing director of the Central Council of Jews in Germany, described “pure hatred of Jews” being presented at the exhibition and noted that Documenta and other German cultural institutions are deeply influenced by the BDS movement. He also said that no one is taking responsibility, criticizing Kassel Mayor Christian Geselle and Schormann specifically for ignoring warnings for months, stating that it is a disgrace that Schormann had not been fired. Then, on July 16, the supervisory board led by Geselle indeed fired Schormann and announced that they will appoint an interim director.

Minister Roth herself has come under quite a bit of criticism, not least because the German state is the ultimate financer of the exhibition. Roth defended the Documenta organizers before the exhibition opened, emphasizing artistic freedom and bringing different positions to the discussion. Many critics condemned this stance, calling for her to step down. Writing in late June that Roth “opened the anti-Semitic BDS door and gate,” Phillip Peyman Engel concluded, “If the promise ‘Never again anti-Semitism’ is not a cheap phrase, and that is certainly the case with the federal government, then the Ministry of Culture must entrust someone who credibly takes action against hatred of Jews. Someone who performs his or her duties with competence and dignity. With her kosher seal for the BDS ideology, Claudia Roth has shown neither the one nor the other.” Roth has changed her position, more clearly distancing herself from Schormann, condemning any manifestation of anti-Semitism (in the Bundestag committee hearing for instance), and promising greater governmental oversight in the future.

In addition to People’s Justice, other artworks have also been vehemently criticized. Several works by Mohammed Al Hawajri entitled Guernica Gaza take scenes from classic paintings and juxtapose Israeli troops in them. There is no depiction of Hamas, the authoritarian rulers of the Gaza Strip. Moreover, the reference to Picasso’s famous Guernica—a depiction of German-perpetuated war crimes during the Spanish Civil War—has also been criticized as deeply problematic especially in a German context. It should be noted that the exhibition space for the Question of Funding and several other locations in Kassel were themselves vandalized with right-wing graffiti.

Even though the discussions and possible consequences are still playing out, what are we to make of the scandal thus far? Organizationally, there was a fundamental failure of oversight and accountability. The images on the banner should never have been exhibited, and someone should have vetted each item. Perhaps this was a failing of the overly decentralized, “anti-authoritarian collective” approach. Perhaps there were misplaced fears over censorship and inhibiting artistic freedom. Perhaps there were sensitivities over yet another example of the Global North exerting power over the Global South. All of this is likely true.

But there is absolutely no excuse and justification for what happened—especially since alarm bells were ringing for months. There is no cultural context in which such blatantly anti-Semitic images would be acceptable. I think this shows that even people who have experienced horrible violence, racism, and oppression can also themselves harbor dangerous, xenophobic, and racist worldviews. No one should get a pass. Moreover, it also shows that the scourge of anti-Semitism is still omnipresent worldwide and that many Germans (and German authorities) still have a lot of work to do going forward. At least Roth is starting to understand, noting in the Bundestag hearing, “Anti-Semitism also exists in discourses that we have perceived thus far too much through the lens of the critique of capitalism and post-colonial discourses.”