Elekes Andor via Wikimedia Commons

“Conservative America Is Waiting”

Thomas Protzman

Thomas Protzman is a Halle Foundation research intern at AGI in fall 2024. He is pursuing a master's degree in International Affairs with a concentration in Human Rights and Global Governance at the Hertie School in Berlin and is currently on academic exchange at the Elliott School of International Affairs at George Washington University. He spent three years in Vienna, completing a teaching fellowship with Fulbright Austria. He earned his undergraduate degree in History from Denison University and studied for a semester at the Ruprecht-Karls Universität in Heidelberg, Germany. Additionally, he brings experience from his time as an intern for U.S. Senator Sherrod Brown. Thomas is committed to strengthening institutional ties and fostering collaborative leadership in the transatlantic sphere. He has a wide range of research interests, including climate change, populism, and institutional trust.

The New Transatlantic Axis?

Last month, two Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) delegations came to Washington. The first, led by AfD parliamentary group vice-chair Beatrix von Storch, included disqualified Ludwigshafen mayoral candidate Joachim Paul. According to von Storch, they held “strategic discussions in the White House with U.S. representatives from the Domestic Policy Council, the Office of the Vice President, the National Security Council, and the State Department” on topics including digital policy and the state of democracy in Germany. The second delegation featured parliamentarians Markus Frohnmaier and Jan Wenzel Schmid. The purpose of their visit? In Frohnmaier’s words, “to explain the goals of AfD foreign policy, promote cooperation, and educate people about the activities of the CDU.” They met with acting Under Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs Darren Beattie “to discuss U.S.-Germany relations, as well as shared priorities on cultural exchange and migration.” Frohnmaier—who has built a brand as a transnational network-builder—serves as deputy leader of the AfD and its foreign policy spokesperson. His time in Washington also included a meeting with students at Georgetown University, where he explored how the AfD could collaborate with a conservative American government in the future and gave an address titled “The Ascending Right in the West.” The message he sent back to Germany: “Conservative America is waiting for the AfD!”

Transnational conservative networks have operated since the mid-1990s, when UN conferences on women’s and reproductive rights triggered an international religious conservative backlash. The World Congress of Families (WCF), founded in 1997, pioneered the model[1] that CPAC and others follow: regular international summits, “conservative ecumenism” bridging theological divides, and a replication strategy where each congress spawned new local organizations. By the 2010s, these networks had secured government backing from Poland’s Law and Justice Party, Hungary’s Fidesz, and Italy’s League Party, with a 2021 report documenting $700 million in funding between 2009-2018. But these remained primarily civil society networks.

What distinguishes this moment is the backing of American politicians and business leaders, elevating what were once unofficial networks into a real transatlantic policy. The Trump administration has publicly denounced the German Brandmauer (firewall)—the refusal by Germany’s traditional parties to cooperate or engage with the AfD—and endorsed candidates in European elections such as Karol Nawrocki, now the president of Poland. The AfD’s co-leader and federal spokesperson Tino Chrupalla attended President Trump’s second inauguration on January 20. In February, Vice President J.D. Vance began his “there’s a new sheriff in town” speech at the Munich Security Conference by talking about Europe and the United States’ shared values—values that he then accused Europe of “retreating from” by “[banning] lawmakers representing populist parties on both the left and the right from participating… There is no room for firewalls,” he exclaimed. “Excellent speech!” responded Alice Weidel, leader of the AfD and candidate for chancellor in the 2025 election. She subsequently met Vance at his hotel. In May, the State Department released a white paper on “The Need for Civilizational Allies in Europe” on Substack, which hoped for “both Europe and the United States [to] recommit to [their] Western heritage” and accused the “global liberal project … [of] trampling democracy, and Western heritage along with it, in the name of a decadent governing class afraid of its own people.” More recently, Trump chose Budapest—which has hosted a Conservative Political Action Conference since 2022 and continues its emergence as a hub of transatlantic illiberalism—to host recently cancelled (or postponed) Russia-Ukraine negotiations in 2025.

These developments reveal an increasingly institutionalized infrastructure, and concrete policy battles bind these alliances. The EU’s Digital Services Act has become a shared enemy: the AfD attacks it domestically as censorship while Vance has threatened to withdraw NATO support unless Europe rolls back the law. On migration, both employ civilizational framing; Trump’s claim that “immigration is killing Europe” echoes AfD rhetoric about defending German identity. The administration has also adopted the AfD’s use of “remigration” and seeks to open an “Office of Remigration.” Climate policy reveals the circuit clearly: the Heartland Institute, an American think tank with connections to the oil and gas industry, known for climate-change denial, recruited 25-year-old German Naomi Seibt, a right-wing internet personality known as the “Anti-Greta [Thunberg],” specifically to combat German climate regulations they feared would be “contagious,” demonstrating how American fossil fuel interests align with the AfD’s anti-Green Deal stance. They are coordinated campaigns targeting the same institutional frameworks, and they are not just located within government. They are being reinforced online by American tech entrepreneurs.

The Role of the Internet

While in Washington, Frohnmaier also met Naomi Seibt. Seibt first spoke at CPAC in 2020. Dubbed “the German Musk whisperer,” she helped facilitate the Tesla founder and then-Trump campaign advisor’s 75-minute conversation on X with Alice Weidel in 2024. On top of that, she has cultivated her own following of over half a million followers on X and YouTube. Seibt moved to Washington, DC, in 2025 and recently applied for political asylum in the United States. Representative Anna Paulina Luna (FL-13) offered to expedite her application. For AfD leaders and influencers like Seibt, X functions as infrastructure. Rather than just a platform, it has become a deliberate bypass of traditional media gatekeepers with algorithmic amplification strategically aligned with their goals. Just as MAGA figures in the United States have leveraged X to communicate directly with supporters, AfD actors like Frohnmaier and Seibt use the platform to broadcast their ideology unfiltered. The control Elon Musk wields over X’s algorithm has been crucial in this strategy: by amplifying right-wing voices and narratives, he effectively creates a pipeline through which these ideas circulate transnationally with minimal interference.

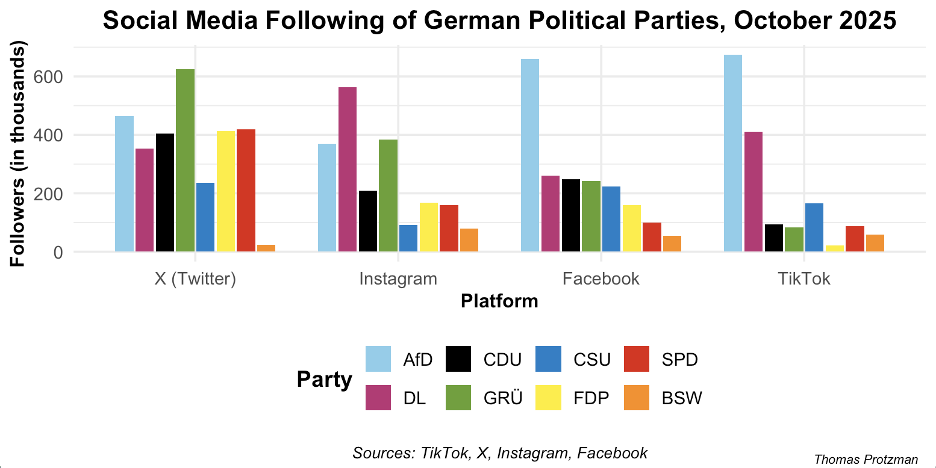

Instagram and TikTok are also media through which the AfD reaches the public. One of the reasons why the AfD is so popular among younger Germans is its TikTok following, the largest of any German party. Notably, Germany’s traditional centrist parties, the CDU, SPD, and the FDP, fail to crack the top three in total social media following, collectively trailing behind the AfD, Die Linke (DL), and the Greens (GRÜ). While centrist parties still dominate parliament, they are losing the battle for online engagement, particularly on platforms favored by younger voters. The AfD’s TikTok following (674,000) dwarfs that of the CDU (93,000) and SPD (88,000) combined, suggesting a generational gap in digital strategy that mirrors the broader patterns of political alienation among German youth.

The AfD’s digital strategy mirrors the tactics of MAGA in the United States and other right-wing populist movements across Europe: cultivating antagonistic, grievance-driven narratives and exploiting the technological affordances of platforms like X, whose moderation and amplification are strategically aligned with their ideological goals. In her July 2025 strategy paper, von Storch put it clearly: “Our goal is to create a situation in which the political divide no longer runs between the AfD and other political currents, but rather is a confrontation between a popular conservative camp and a self-radicalizing left-wing camp, similar to the situation in the United States.” In just over a decade, what was once dismissed as fringe in Germany now finds resonance not only domestically but across the Atlantic and is amplified through both human and algorithmic networks. Frohnmaier and Seibt’s filmed meeting exemplifies this. Seibt posted clips of the meeting with English translations on X, prompting replies from users in both German and English.

The Paradox: Networked Nationalism

One of the most striking aspects of the strategy is the tension between right-wing nationalist ideology and its explicit effort to leverage external validation and guidance from abroad. This creates a paradox: the AfD frames itself as defending Germany from foreign influence, yet it actively cultivates foreign allies. These alliances are not about open economic or cultural globalization but about networked ideological support. The contradiction becomes clearer when comparing the party’s rhetoric to its actions. Right-wing voices frequently denounce international figures like George Soros as meddling in their domestic politics, framing such actors as threats to sovereignty. Yet U.S.-based actors—be it Trump, Vance, Musk, Peter Thiel, CPAC, or the Heartland Institute—are playing a very similar role, providing resources, visibility, and strategic counsel, but without eliciting the same criticism. This selective engagement seems to indicate that the AfD’s nationalist stance is instrumental rather than absolute: international allies are embraced when they reinforce the party’s ideological and electoral goals. In effect, the AfD and its transnational partners have developed a new networked model of nationalism. It may be paradoxical, but it is also strategically coherent: domestic nationalist appeal is strengthened through international ideological reinforcement, creating a feedback loop where ideological global alliances legitimize domestic ambitions while maintaining the narrative of defending national sovereignty. Naomi Seibt embodies the circuit’s logic. She is simultaneously an insider and interpreter, proof of concept and recruiting tool, making German far-right politics legible and appealing to American conservatives while channeling American rhetoric and ideology back to Germany.

The transformation of transatlantic conservative networking carries significant implications. Traditional U.S.-German engagement operated through established channels: party foundations, think tanks, diplomatic corps, and multilateral institutions. These systems were designed assuming liberal democratic actors were operating in good faith. When opposition parties cultivate foreign state backing before entering government, when tech platform owners algorithmically amplify parties challenging democratic norms, when U.S. officials meet with parties other democracies have cordoned off—the rules of engagement have fundamentally changed. If the AfD enters Germany’s federal government with these American connections already established, it would represent an unprecedented alignment: Europe’s largest economy governed by a party with direct pipelines to White House policymaking and American tech infrastructure. The transatlantic relationship would thus endure, but its founding liberal democratic assumptions are being systematically dismantled from within.

[1] Kristina Stoeckl & Phillip M. Ayoub, “Transnational Illiberal Networks,” in Oxford Handbook of Illiberalism, ed. Marlene Laruelle (Oxford University Press, 2023), 827-846.