Elvert Barnes via Flickr

From Shame to Pride to Propaganda

Lui Mess

rubicon e.V.

Lui Mess is a queer, non-binary lesbian working at rubicon e.V., one of Germany's largest queer counseling centers. As Volunteer Coordinator for the project, "Diqui – Democracy is Queer and Intersectional," Lui facilitates the engagement of diverse queer communities in a democracy-promoting process while fostering intersectional practices within queer spaces. The project focuses on strengthening connections between different queer groups and advancing inclusive, participatory structures.

Alongside their professional work, Lui is pursuing a Master's degree in Gender & Queer Studies at the University of Cologne. Their academic journey is shaped by their research project, "Queerschnitt: Current State of Queer (Counseling) Centers in Germany," which critically examines the organizational structures, intersectional approaches, and challenges faced by queer counseling centers nationwide. The insights gained from their work at rubicon have been instrumental in advancing this research. Beyond their professional and academic endeavors, Lui has volunteered with the Anti-Discrimination Project for Sexual and Gender Diversity in Schools at SCHLAU Köln e.V. Currently, they are working on their master's thesis, "Lesbian & Queer Spaces in Cologne – Where Have They Gone? Documenting and Mapping Spatial Change."

Michael Guston

George Mason University Police Department

Michael Guston has been a law enforcement professional for thirty-six years. He is currently a captain with the George Mason University Police Department in Fairfax, Virginia, where he oversees two satellite campus police stations in neighboring cities. In addition, he manages the IT and Technology department, which is responsible for in-car police computers and report-writing software. Michael is also the department’s LGBTQ+ Liaison Officer, a position he helped create in 2010 to enhance the relationship between the police department and the university’s LGBTQIA+ community. As the LGBTQ+ Liaison Officer, Michael has participated in many local and international LGBTQ+ law enforcement events and conferences. At these conferences, LGBTQ+ officers shared their efforts to establish inroads within the queer communities where they serve and attended classes on various LGBTQ+ topics.

The Political Afterlives of the Pink Triangle

Symbols wield profound political significance, particularly within marginalized communities. They emerge from histories of exclusion and become tools of identity, resistance, and collective memory. For LGBTQ+ communities, symbols like the pink triangle encapsulate both historical trauma and activist empowerment. Their meanings are shaped by political struggle and evolving cultural contexts.

First imposed by the Nazi regime to stigmatize and persecute homosexual men, the pink triangle was reappropriated beginning in the 1970s by the gay movement in West Germany, which integrated memories of the symbol into activism, historical narratives, and collective identity—despite the fact that most activists had not personally experienced Nazi persecution.[1] Today, however, it is again at risk of distortion, as right-wing actors in both Germany and the United States co-opt its imagery to undermine queer memory and rights.

Origins of the Pink Triangle under National Socialism

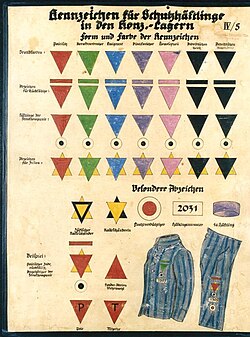

The pink triangle Rosa Winkel originated within the Nazi concentration camp classification system, designating men incarcerated under Paragraph 175 of the German Criminal Code. Following the law’s expansion in 1935, arrests of suspected homosexuals increased dramatically. As historian Dr. Jake Newsome notes, the triangle served as a “visual mechanism through which the Nazi regime sought to annihilate queer identity by isolating it, exposing it to violence, and stripping it of social belonging.”[2]

Prisoners marked with the pink triangle faced particularly harsh conditions, including grueling forced labor and systemic abuse from both guards and fellow inmates. Dr. Albert Knoll, archivist and scholar at the Dachau Memorial Site, has emphasized the uniquely brutal treatment of these prisoners. Newsome describes this targeted dehumanization as a process of symbolic annihilation, designed to erase queer existence from public consciousness.

After 1945, Paragraph 175 remained in effect in West Germany. Persecuted individuals were denied reparations and social recognition. Newsome calls this a “double exclusion”[3]: persecution under Nazism followed by postwar silence. Paragraph 175 was only abolished by the German Bundestag on June 11, 1994. Changes to the law in 1969 had ended the criminal prosecution of consenting adults in a homosexual relationship. It took another twenty-five years for the law to be eliminated altogether.

Reclaiming the Triangle: Activist Transformations in Germany and the United States

Germany

In the 1970s, West German queer activists began reclaiming the pink triangle as a counter-symbol of remembrance and protest. The publication of Die Männer mit dem Rosa Winkel in 1975, the first memoir by a gay concentration camp survivor, reintroduced the symbol into public discourse. Groups such as Homosexuelle Aktion Westberlin (HAW) used the triangle prominently in demonstrations and adopted it as the name of their publishing house, Verlag Rosa Winkel.

This reappropriation was simultaneously commemorative and political. It honored those persecuted under the Nazi regime while protesting the continued enforcement of Paragraph 175 in the Federal Republic. As Newsome observes, the triangle became “a political tool to expose postwar injustices and demand inclusion in national memory.”[4] Activists placed the symbol in memorials like Dachau and Sachsenhausen, using slogans such as “Wir waren dabei” (“We were there, too”) to assert queer historical presence. Historian Craig Griffiths situates these efforts within a broader “memory boom” in 1970s queer politics, shaped by the legacies of 1968 and the rise of human rights discourse.[5]

United States

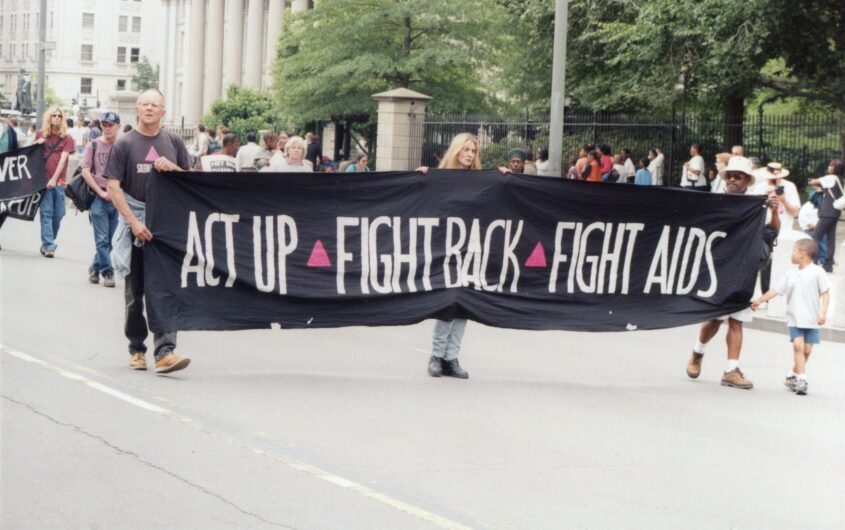

In the 1980s, as the AIDS epidemic devastated queer communities, the Silence=Death Collective in New York created a striking visual protest: a pink triangle, inverted and set against a black background, with the phrase “Silence = Death.” This symbol, reclaiming a mark of Nazi persecution, became a call to resist indifference and demand action.

The emblem gained wide recognition through its adoption by ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), founded in 1987. ACT UP used the triangle as a visual anchor for civil disobedience and protest, recontextualizing it as a signifier of rage, solidarity, and militant queer politics. In this context, the triangle became an international emblem of resistance—its transformation from stigma to defiance emblematic of queer resilience.

Right-Wing Appropriations: Trump, the AfD, and the Re-Instrumentalization of the Pink Triangle

United States: Trump’s Symbolic Manipulation

In recent years, elements of the U.S. far right have attempted to appropriate LGBTQ+ imagery to advance exclusionary agendas. Donald Trump’s ‘Trump Pride’ campaign, for instance, sought to present his administration as inclusive while actively undermining LGBTQ+ rights. This paradox is part of a broader trend described by scholars such as Jasbir Puar and Christina Hanhardt, in which queer identities and symbols—like the pink triangle—are selectively absorbed into nationalist and neoliberal frameworks.[6] Through this symbolic rebranding, queer visibility is sanitized and instrumentalized to obscure ongoing structural violence and to recast nationalism as tolerant and inclusive. The Trump administration has implemented policies from Project 2025, which includes rolling back LGBTQ+ rights and protections and reinforcing a rigid definition of gender. This aligns with the idea that nationalist movements strategically deploy LGBTQ+ representation while simultaneously enacting policies that harm the community.

As president, Trump reposted a 2023 article from the Washington Times criticizing LGBTQ+ representation in military recruitment. The accompanying image showed a triangle overlaid with a “NO” symbol—an unsettling visual echo of the pink triangle’s original use. Although the post included no text, its symbolism reinforced a rhetoric of exclusion masked as critique.

Germany: AfD and Attacks on Queer Memory

In 2023, Germany’s far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) circulated an image of a rainbow-colored triangle with the caption “Gendern ist Zwang” (“Gendering is coercion”). This act mimicked the pink triangle worn by those imprisoned for homosexuality under National Socialism, turning a symbol of persecution into a weapon against contemporary LGBTQ+ rights.

The response was swift. Historian Jens-Christian Wagner, director of the Foundation of Memorials in Lower Saxony, condemned the image as a “double transgression”: an assault on both the dignity of queer Holocaust victims and academic freedom. He called it “disgusting, unconstitutional, homophobic, and revisionist.”

Activists likewise denounced the appropriation, warning of its retraumatizing effects and its potential to erode decades of remembrance work. Rather than silencing queer memory, the AfD distorts it—employing symbolic violence to undermine solidarity and deny queer history its rightful place in public consciousness.

Conclusion: The Struggle over Symbolic Memory

The pink triangle remains a charged and contested emblem—simultaneously a site of trauma, remembrance, and resistance. Its shifting meanings reflect the volatility of queer visibility and the precariousness of symbolic power.

As reactionary forces seek to neutralize or reverse the triangle’s legacy, it becomes all the more urgent to defend its historical integrity through critical remembrance and public pedagogy. LGBTQ+ communities continue to reassert their narratives by reclaiming symbols, reshaping memory, and mobilizing against erasure.

In this ongoing struggle, the pink triangle stands not only as a reminder of past persecution but also as a testament to the transformative force of queer activism. As José Esteban Muñoz reminds us, queerness is not merely what has been but also what is yet to come—a horizon of collective resistance shaped through memory, imagination, and solidarity.[7]

[1] Jake Newsome, Pink Triangle Legacies: Coming Out in the Shadow of the Holocaust (New York: Cornell University Press, 2022), p. 7.

[2] Newsome, p. 25.

[3] Newsome, p. 51.

[4] Newsome, p. 87.

[5] Craig Griffiths, The Ambivalence of Gay Liberation: Male Homosexual Politics in 1970s West Germany (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021, p. 126.

[6] Jasbir K. Puar, Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007).

Christina B. Hanhardt, Safe Space: Gay Neighborhood History and the Politics of Violence (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013).

[7] Michael Bronski, A Queer History of the United States (Boston: Beacon Press, 2011).

Cathy Cohen, “Punks, Bulldaggers, and Welfare Queens: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics?” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 3, no. 4 (May 1997), p. 437–465.

José Esteban Muñoz, Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999).

This article is part of the project “Building LGBTQ+ Communities in Germany and the United States: Past, Present, and Future” and is generously funded by the Transatlantik-Programm der Bundesrepublik Deutschland aus Mitteln des European Recovery Program (ERP) des Bundesministeriums für Wirtschaft und Klimaschutz(BMWK) (Transatlantic Program of the Federal Republic of Germany with Funds through the European Recovery Program (ERP) of the Federal Ministry for Economics and Climate Action (BMWK)).