Remembering Pulse

Lisa Schnurpfeil

Atlantik-Brücke e.V.

Lisa Schnurpfeil was born and raised in East Germany. After completing their high school education, Lisa pursued a degree in North American studies at the Free University of Berlin. In their thesis, Lisa focused on the role of narratives around masculinity and male supremacy in the ideology of the right-wing extremist group ‘The Proud Boys’.

Currently, Lisa is working as a Program Manager of the New Bridge Program at Atlantik-Brücke e.V. This fellowship offers young professionals from historically underrepresented communities in the United States and Germany the opportunity to learn about and contribute to the transatlantic dialogue over the course of a ten-day program. In this role, Lisa has helped to conceptualize, plan, and execute several cross-cultural study trips, conferences, and events. Outside of their professional role, Lisa is part of a collective that organizes a yearly weekend-long cultural event offering workshops, music performances, and a community experience.

Natalie Adams-Menendez

Office of Democratic Leader Hakeem Jeffries

Natalie Adams-Menendez is a Staff Assistant to the Executive Office of Democratic Leader Hakeem Jeffries. She began her congressional tenure as a staffer with Team Jeffries in the House Democratic Caucus in 2022. Previously, she interned with the House Democratic Caucus as an LGBTQ Victory Institute congressional intern and with the office of LGBTQ Equality Caucus Co-Chair Sharice Davids (KS-03).

Natalie grew up in Lawrence, Kansas and graduated with honors from Stanford University, where she majored in international relations and double minored in French and human rights. Her commitment to human rights work drives her passion for politics and legislation, and she is dedicated to applying her background in these subjects to domestic and international LGBTQ rights issues.

The Power of Community-Driven Collective Memory

Natalie Adams-Menendez: Reflection

Days before I turned seventeen, I awoke to news that 49 people had been killed and at least 53 others had been injured at a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida. At the time, I was living in Kansas in the heartland of the United States as someone who was queer, a young person, a dancer, and Latina. The Pulse nightclub shooting was the largest mass shooting in U.S. history to date in 2016, and it remains the largest attack targeting the LGBTQ+ community in America. Yet due to the shooting’s characterization in the media as a terrorist act of violence, I did not feel connected to the Pulse atrocity. I did not see myself within my murdered communities. Standing in front of the Interim Pulse Memorial in 2023, everything changed.

As part of the inaugural cohort of the AGI program Building LGBTQ+ Communities in Germany and the United States, we had the opportunity to visit the Pulse Interim Memorial dedicated to the memory of 49 young, predominantly Latinx and Black people who were killed on June 12, 2016, as they danced at the Pulse gay nightclub’s Latin Night in Orlando, Florida. In the week leading up to our program, I sat in trepidation as I reacquainted myself with the Pulse attack and further researched its victims. I was anxious to see how, seven years later, the attack would be framed. As someone who shares communities with those who were murdered, I was also worried. How would I respond? My question would be answered on November 15, 2023, during AGI’s trip to the Pulse Interim Memorial.

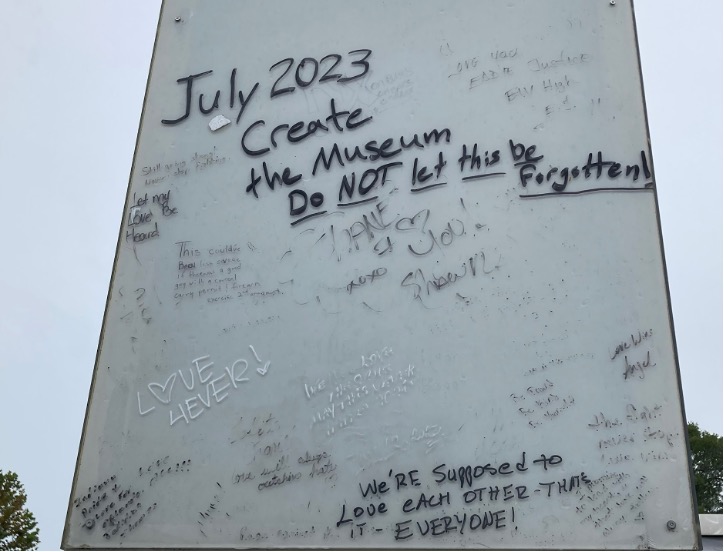

There are two ways to enter the Pulse Interim Memorial. Coming from S Orange St., the first marking of the Pulse nightclub is its sign looming from the sidewalk. Covered in notes and drawings, the community graffitied this sign in the wake of the shooting with bilingual messages of solidarity, love, and support for the victims and survivors. In more recent additions, the sign now carries messages of protest against the rise in homophobia and transphobia brought on by demagogues like former President Donald Trump and Florida Governor Ron DeSantis. It shouts phrases like “we say gay” and the slogan “love wins.” Seven years after the Pulse Interim Memorial’s creation, the newest dated comment comes from July 2023 and is a reflection on the status and importance of a permanent Pulse memorial. With urgency, it reads “create the museum – do not let this be forgotten!”

While our cohort entered the Pulse Interim Memorial from S Orange St., the official W Esther St. entrance greets you in both English and Spanish with a message from the onePULSE Foundation. The entrance sign lists the interim memorial’s mission as being a “sanctuary of love, hope, and healing that remembers the 49 lives taken in a senseless act of violence” and is “dedicated to the affected survivors and all those left behind.” Visitors are welcome to leave messages of hope—an invitation that the Orlando community has accepted and that is showcased in the many personalized posters for victims put up in both English and Spanish alongside the walls of the walkway. The onePULSE and community use of English and Spanish throughout the space serves as a testament to the diversity of those lost. They were, and they were loved by, English and Spanish speakers. They were Latinx, immigrants, and LGBTQ+.

While our cohort entered the Pulse Interim Memorial from S Orange St., the official W Esther St. entrance greets you in both English and Spanish with a message from the onePULSE Foundation. The entrance sign lists the interim memorial’s mission as being a “sanctuary of love, hope, and healing that remembers the 49 lives taken in a senseless act of violence” and is “dedicated to the affected survivors and all those left behind.” Visitors are welcome to leave messages of hope—an invitation that the Orlando community has accepted and that is showcased in the many personalized posters for victims put up in both English and Spanish alongside the walls of the walkway. The onePULSE and community use of English and Spanish throughout the space serves as a testament to the diversity of those lost. They were, and they were loved by, English and Spanish speakers. They were Latinx, immigrants, and LGBTQ+.

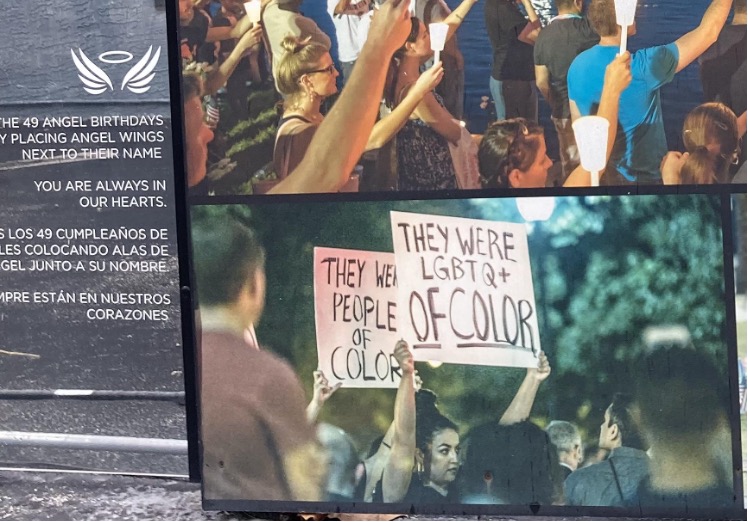

Behind both entrances, the bulk of the Interim Pulse Memorial consists of a photo wall with submissions from the Orlando community. Pictures of vigils, Pride celebrations, and signs line the glass walls surrounding the nightclub. Amidst these—albeit relegated to the bottom corner of the wall—is a photo of people holding signs reading “they were LGBTQ+ of color.” In the Interim Pulse Memorial, with its direct invocation of intersectionality and its bilingual messages from both the onePULSE Foundation and the community, it is impossible to forget or suppress the fact that most of the victims of the Pulse shooting were Latinx and/or Black. Not only were they LGBTQ+, they also were of color.

Standing in front of the Pulse Interim Memorial was a cathartic experience. As a queer Latina, the Pulse Interim Memorial, specifically the contributions of the queer or allied Latinx community, provided a perspective and source of care that I needed to feel and fully process the atrocity that the Pulse shooter committed against my communities. But will the Pulse Interim Memorial’s explicit intersectionality persist in the permanent memorial for others to also experience? Or will the permanent Pulse Memorial, such as the initial media reactions to the shooting, lack representation of the many communities that lost loved ones on June 12, 2016?

Lisa Schnurpfeil and Natalie Adams-Menendez: Remembrance

Mirroring the objectives of our trip, memorials serve as a link between the public and the past, present, and future. They preserve the history of specific events, ensuring that their occurrence remains present in public memory, and provide a platform for communities to collectively remember.[1] Moreover, memorials embody and manifest public consciousness and political memory. The specific perspective on the past and future highlighted by a monument becomes universalized through it, influencing how societies affected by such events comprehend and navigate their history. Memorials play a pivotal role in shaping a society’s cultural and political values through memory-political action in public spaces, seeking cultural hegemony by shaping the everyday consciousness of a population.[2]

The power of memorials to shape beliefs underscores the importance of considering who controls the narrative and perspective commemorated through the Pulse Memorial.

The memorial we visited was developed in the immediate aftermath of the Pulse tragedy as an interim memorial for the victims and survivors of the attack. It was to be ephemeral and transitional. But what will be the Pulse attack’s legacy? Before our visit to the Pulse Interim Memorial, our cohort was scheduled to meet with the onePULSE Foundation, the organization responsible for raising money to develop a permanent memorial for the victims and survivors of the Pulse shooting. However, in the weeks before our trip, the onePULSE Foundation imploded and is now permanently closed. Through our cohort’s conversations with local stakeholders, responses to onePULSE’s views and management were mixed, particularly concerning questions about raising revenue for the memorial via a gift shop and about how finances for the memorial’s development were proceeding. But while stakeholders’ views differed on what to do with Pulse, everyone agreed that there must be a permanent form of remembrance for the attack.

Through our conversation with the City of Orlando’s Director of Multicultural Affairs, Luis Martinez, our cohort learned that the City of Orlando had bought the Pulse nightclub and was now responsible for designing its permanent memorial. Recent developments have confirmed the city’s involvement moving forward. In our discussion, Mr. Martinez explained that every effort will be made to involve survivors and families of the victims, most of whom were immigrants and people of color, in the process. There will be a continuing conversation to ensure that the Pulse community’s vision is incorporated into the final memorial. But is that conversation enough, and who will the permanent Pulse Memorial now serve?

Through our conversation with the City of Orlando’s Director of Multicultural Affairs, Luis Martinez, our cohort learned that the City of Orlando had bought the Pulse nightclub and was now responsible for designing its permanent memorial. Recent developments have confirmed the city’s involvement moving forward. In our discussion, Mr. Martinez explained that every effort will be made to involve survivors and families of the victims, most of whom were immigrants and people of color, in the process. There will be a continuing conversation to ensure that the Pulse community’s vision is incorporated into the final memorial. But is that conversation enough, and who will the permanent Pulse Memorial now serve?

Lisa Schnurpfeil: Representation

The impact of memorials goes beyond remembrance; it shapes societal hierarchies. Social power structures are heavily influenced by the way history is remembered. Thus, if a monument fails to accurately represent the perspectives of the affected communities, it will influence how these groups are perceived by the larger society. Moreover, if a memorial neglects to represent the marginalized communities affected by an event, the risk that these groups will be overlooked by systems of power increases.[3] This underscores the importance of involving survivors and affected communities in memorialization processes, especially when addressing the traumas experienced by these communities.

As the Pulse shooting also affected a highly marginalized group within the queer community—queer Latinx and people of color—the memorial commemorating this tragic incident should include the voices of the affected communities and acknowledge the systemic oppressions that these groups face. Given the profound impact memorials have on public consciousness and collective memory, it is imperative that the City of Orlando center the survivors and families of the victims in their conversation regarding the design and message of a new permanent memorial. The significant influence of the perspective highlighted through a memorial on the culture of remembrance within a community underscores the importance of inclusive decision-making processes.

As the Pulse shooting also affected a highly marginalized group within the queer community—queer Latinx and people of color—the memorial commemorating this tragic incident should include the voices of the affected communities and acknowledge the systemic oppressions that these groups face. Given the profound impact memorials have on public consciousness and collective memory, it is imperative that the City of Orlando center the survivors and families of the victims in their conversation regarding the design and message of a new permanent memorial. The significant influence of the perspective highlighted through a memorial on the culture of remembrance within a community underscores the importance of inclusive decision-making processes.

Furthermore, the future Pulse Memorial will play a vital role in transmitting information about the Pulse shooting, especially to younger generations. This role becomes even more crucial in light of the recent restrictions on access to information on LGBTQ+ issues in Florida. Legislation such as the “Don’t Say Gay Bill,” which severely limits education on LGBTQ+ topics within public education, makes the Pulse memorial a significant source for understanding the history of the Pulse shooting and the broader queer rights movement along the frontlines of Florida. The power of memorials to shape beliefs underscores the importance of considering who controls the narrative and perspective commemorated through the Pulse Memorial and ensuring a comprehensive and accurate portrayal of the history of the Pulse shooting for future generations.

[1] Ebru Erbaş Gürler and Basak Ozer, “The Effects of Public Memorials on Social Memory and Urban Identity,” Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 82 (July 1, 2013): 858–63, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.361.

[2] Ariane Eichenberg, Christian Gudehus, and Harald Welzer, Gedächtnis Und Erinnerung. Ein Interdisziplinäres Handbuch, (J. B. Metzler’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung & Carl Ernst Poeschel GmbH, 2010), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-476-00344-7.

[3] Sharon K. Hom and Eric K. Yamamoto, “Collective Memory, History, and Social Justice,” UCLA Law Review 47, no. 6 (August 2000): 1747–1802.

This article is part of the project “Building LGBTQ+ Communities in Germany and the United States: Past, Present, and Future” and is generously funded by the Transatlantik-Programm der Bundesrepublik Deutschland aus Mitteln des European Recovery Program (ERP) des Bundesministeriums für Wirtschaft und Klimaschutz(BMWK) (Transatlantic Program of the Federal Republic of Germany with Funds through the European Recovery Program (ERP) of the Federal Ministry for Economics and Climate Action (BMWK)).