pedrik via Flickr

Inflation: Pressure is easing, but it will not disappear completely

Jörn Quitzau

Bergos AG

Joern Quitzau is a Geoeconomics Non-Resident Senior Fellow at AGI. He is Chief Economist at Bergos, a private bank based in Switzerland. He specializes in economic trend research and economic policy. Joern Quitzau hosts two Economics podcasts.

Prior to his position at Bergos, Joern Quitzau worked for Berenberg in Hamburg (2007-2024) and Deutsche Bank Research in Frankfurt (2000-2006) with a special focus on tax and fiscal policy.

Dr. Quitzau (PhD, University of Hamburg) was a Visiting Fellow at AGI in April 2014 and September 2022 and an American-German Situation Room Fellow in April 2018.

The statisticians who calculate the inflation rate have had a challenging job over the past three years. The calculation of the inflation rate is based on the consumer price basket which exhibits certain limitations. In normal economic times, people’s consumption follows fairly consistent patterns. Inflation rates can be calculated quite reliably. But with the onset of the pandemic, the situation became considerably more complicated and challenging.

With the COVID lockdowns and other restrictions, consumers have been unable to consume as they used to. Large parts of services and goods used to determine inflation rates were unavailable for purchase. In Germany, up to 25 percent of the goods and services which are used for the inflation measurement were affected by the lockdowns and other pandemic-related measures (e.g. vacation trips, concerts, restaurant visits). To ensure comparability with previous years, the Federal Statistical Office (Statistisches Bundesamt) has provisionally assumed that these products remained available for purchase at unchanged prices from the previous year. That’s not quite right, but no other approach existed. In any case, the validity of the inflation rate suffered, resulting in distorted measurements.

Pent-up demand drives up prices

Once the coronavirus restrictions ended, a substantial surge in demand ensued, leading to unusually strong price increases. Global supply bottlenecks contributed to this. The situation was exacerbated, particularly within Europe, by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The associated energy crisis temporarily increased energy (and food) prices to extreme levels. Consumers were compelled to readjust their consumption behavior once more. It is extremely difficult to measure inflation accurately in times of unstable consumption patterns.

However, prices have risen so sharply on both sides of the Atlantic over the past two years that the inaccuracies outlined can only account for a small part of the upward pressure on prices. In the United States, the inflation rate peaked at 8.9 percent (June 2022), while in the eurozone, the inflation rate rose to 10.6 percent and in Germany even to 11.6 percent (October 2022). In the meantime, the trend is downward. In the United States, the inflation rate has recently fallen to 6.0 percent (February 2023), while in the eurozone and Germany, it has dropped to 6.9 percent and 7.8 percent (March 2023). However, inflation rates still exceed the 2 percent target set by the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) and the European Central Bank (ECB). Pressure to act therefore remains for the central banks.

Energy crisis in Europe

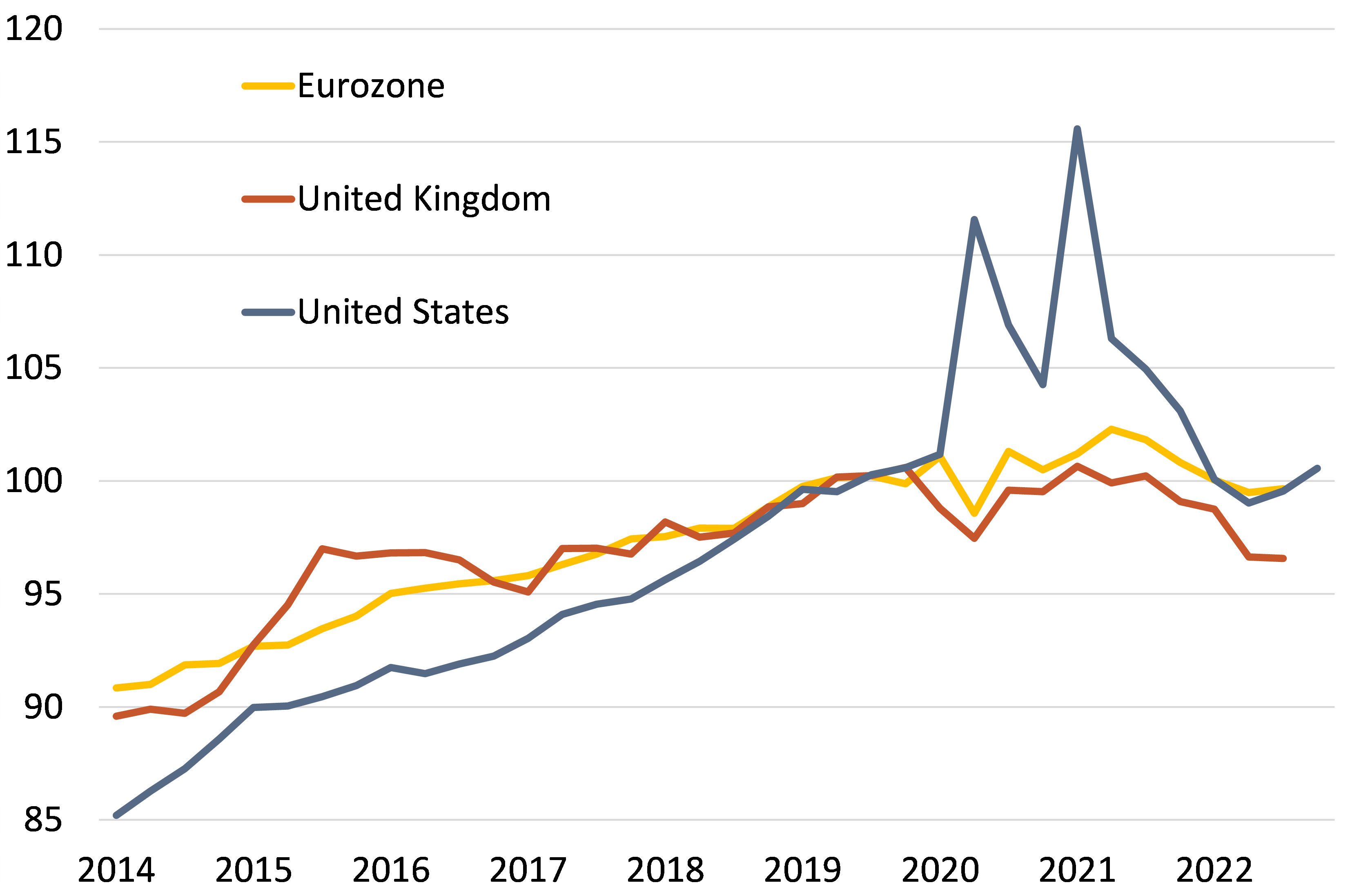

To see where the journey is headed, a brief analysis of the origin of inflation is necessary. Even though the extent of the overshoot and the trajectory are similar on both sides of the Atlantic, there are notable differences. In particular, the similarities can be found in the post-pandemic pent-up demand and global supply shortages. One difference, however, is that pent-up demand in the United States was stimulated by much looser monetary and fiscal policies. Accordingly, inflation in the United States is very much driven by demand (see chart 1). In contrast, the issues in Europe were mainly on the supply side. The war in Ukraine rose food and gas prices to unprecedented levels. By contrast, the United States has been less affected by increasing energy prices due to its self-sufficiency in this area.

Chart 1: Real disposable income

Disposable income, deflated by headline CPI; 2019 = 100. Sources: BEA, ONS, Eurostat, Berenberg

Central banks must deliver

Inflation in the United States is therefore more homemade (loose fiscal policy), while in Europe it is more dependent on imports (energy dependency). The Fed has an advantage over the ECB as it can effectively reduce demand-driven inflation through its interest rate policy. The ECB, on the other hand, has difficulties dampening upward pressure on prices that comes from the supply side. Nevertheless, the ECB can undertake two measures to address inflation: Firstly, by pursuing a credible monetary policy, it can prevent inflation expectations from becoming unanchored. If inflation expectations increase significantly, economic agents start to bring forward planned purchases. That is the way to benefit from the currently more favorable price level. However, this results in an increase in demand, so the fear of rising prices actually leads to further rising prices. Therefore, it is crucial that central banks take measures to anchor inflation expectations at low levels. Secondly, a credible, stability-oriented monetary policy has a positive effect on the exchange rate. The ECB’s hesitancy—it only initiated the interest rate turnaround four months after the Fed—has contributed to the weak external value of the euro. As the U.S. dollar is in high demand as a safe haven, the strength of the dollar and weakness of the euro occurred simultaneously. The euro exchange rate fell to a low of $0.96 per euro, well below its fundamental fair value of around $1.20 per euro. Since a weak exchange rate results in higher import prices, inflation in the eurozone was fueled by the exchange rate, while it was dampened in the United States.

Where do we go from here?

The price surge of the past two years cannot be reversed. Price levels will remain at a significantly higher level. But growth rates will continue to decline due to a statistical effect known as the base effect: Inflation rates are usually calculated by comparing prices to the same month in the previous years. If prices had already increased considerably twelve months ago and there are no additional price drivers added in the meantime, inflation rates will decline sharply. This is exactly the effect we anticipate for the current year. In Germany, with a bit of luck, the inflation rate could return to below 3 percent in December 2023—after more than 9 percent inflation at the start of the year in January. The average annual inflation rate for 2023 is likely to be around 6 percent.

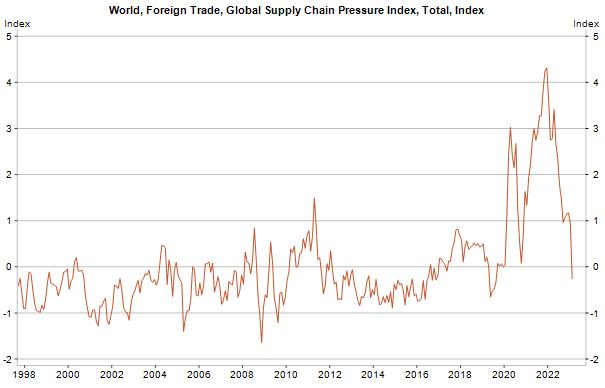

Inflationary pressure is also easing significantly due to a decrease in energy prices, a reduction in freight rates, and the easing of global supply bottlenecks.

Source: Macrobond

In the short term, the most significant risk is the occurrence of a wage-price spiral. The more workers succeed in cushioning the loss in purchasing power by negotiating higher wages, the more persistent the upward pressure on prices will be. Given the labor shortages in the United States and Germany, workers have good negotiating positions.

However, even after inflation subsides, inflation is unlikely to return to the very low levels of the last decade. Several structural reasons such as heightened pricing of CO2 emissions, increasing labor scarcity (rising wage pressure), and deglobalization advocate for the existence of persistently higher inflation rates—surpassing the central bank targets of 2 percent.