IgorCalzone1 via Wikimedia Commons

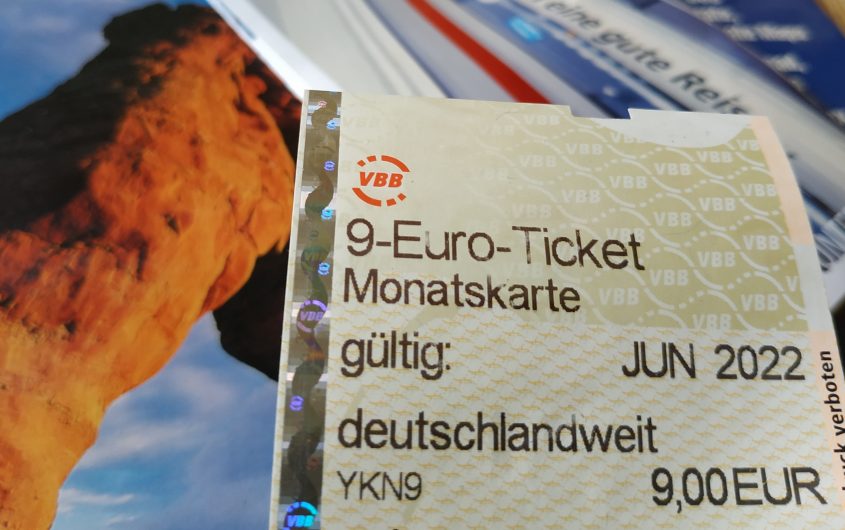

The 9-Euro Ticket

Clara S. Thompson

University of Jena

Clara S. Thompson is a German-American author, climate activist, and community organizer. She co-founded the Wald Statt Asphalt (Forests instead of Asphalt) Alliance and was a spokesperson in a recent campaign to save the Dannenröder Forest from being cut down for a new highway project. She regularly writes for the progressive German Newspaper Neues Deutschland. A graduate in cultural studies from the University of Leipzig, she is currently enrolled in a post-graduate program in sociology at the University of Jena. Her current focus is on empowering people to organize within their communities and to work towards a mobility transition away from automobile dependence towards improved public transport.

A one-off low-cost and climate friendly public transportation measure in Germany has expired. Will the German government continue it?

The 9-euro ticket, a one-time, low-cost public transportation measure introduced in response to rising inflation and prices following the start of the war in Ukraine, expired on August 31. Despite its clear success, which involved reducing pollution, easing traffic, and enabling people to take long-postponed trips to see family, the German government has not been able to agree to continue it beyond the end of August.

When the government of New Zealand announced in early April 2022 that it would make public transport half as cheap, I remember saying to friends that this would not be possible in Germany. Public transport has always been expensive in Germany, while car driving has been affordable through measures such as cheap parking, gasoline subsidies, and free highways. Given that the car industry accounts for 10 percent of German GDP, this might not come as a big surprise.

Scientists, mobility experts, and civil society players agree that Germany will have to go far beyond producing electric cars to effectively transform the transportation sector to meet Germany’s climate goals. German car companies like Volkswagen are currently working to produce more electric cars, calling this process a “green transition.” But electric cars also require roads and produce even more CO2 emissions during their production than cars with an internal combustion engine. In addition, the increase in lithium mining (lithium is needed for the battery) is associated with environmental problems: Current forms of extraction require large amounts of energy or water, which are becoming increasingly scarce in many regions of the world. Transforming the auto industry into a “mobility industry” that produces only few cars and mainly trains and railroads will therefore be a crucial part of an effective climate policy, as will major investment in public transport and rail.

To many citizens’ astonishment the German government announced its energy relief package (Energie-Entlastungspaket) at the end of April—and with it the 9-euro ticket. For three months, Germans were allowed to buy a ticket for 9 euros per month and use the regional trains in the whole of Germany.

In the course of those months, 52 million tickets were sold. Another 10 million subscription customers were also allowed to use the ticket with their already-existing subscriptions. Overall, 1.8 million tons of CO2 were saved—the equivalent to the powering of 350,000 homes. The scheme is also likely to have helped keep inflation, currently around 8 percent, 2 percentage points lower than it would otherwise have been. 88 percent of Germans said by the end of the three months that they were either content or very content with the ticket.

The 9-euro ticket has cost taxpayers 2.5 billion euros. Compared with Transportation Minister Volker Wissing’s plans to invest 70 billion in the auto industry—including for electric and hybrid vehicles—this year, it may not seem like a lot.

Support for the ticket was definitely not a given, as there have been many complaints about full or delayed trains in the last three months, and people living in the countryside have generally been less satisfied with the ticket. This may not be surprising, considering that public transport in rural areas is not well-developed in Germany, with 15,000 km of rail lines having been closed since the car boom in the 1960s. In the past, most of the funds for mobility and public infrastructure in Germany were invested in cars or highways: In 2019, for example, Germany spent 56 percent of the funds earmarked for infrastructure on the maintenance and construction of roads. For comparison, Luxembourg invested almost two-thirds of the funds in the rail network.

In recent weeks, a political debate has erupted over the extension of the 9-euro ticket with the government and regional administrations being under huge pressure to continue the ticket in some form. The SPD and the Greens, as part of the government, and many environmental groups are in favor of the extension because the ticket has helped to reduce inflation and made public transport more affordable. On the other hand, unions such as the Gewerkschaft Deutscher Lokomotivführer (GDL, German Train Drivers’ Union) are not in favor of the extension, saying working conditions are no longer sustainable. They argue that the government must first invest in railway infrastructure before making public transport cheap. The liberal FDP, also part of the coalition and in charge of the finance ministry, rejects the idea of a free ticket for public transport for similar reasons, arguing not enough funds are available to finance it. Currently, the government is discussing plans to introduce a regional ticket that would cost between 49 and 69 euros—but many activists and initiatives criticize this, arguing that the ticket could actually be made cheaper so that more people could afford it.

The 9-euro ticket has cost taxpayers 2.5 billion euros. Compared with Transportation Minister Volker Wissing’s plans to invest 70 billion in the auto industry—including for electric and hybrid vehicles—this year, it may not seem like a lot. Many environmental organizations argue that the money for the ticket could be made available—it has been made available for years for car industry subsidies, for example. According to a new study by Greenpeace, the German government could earn up to 46 billion euros a year by eliminating these climate-damaging subsidies—and also save a massive amount of CO2. They suggest cutting for example the company car privilege (Dienstwagenprivileg), which allows owners of company cars to use their company car during their time off for a low price and costs taxpayers around 5 billion a year.

Greenpeace further argues that a cheap price for public transport is not just feasible, it is also necessary. According to their study, households with particularly low incomes fall completely through the cracks when it comes to using the classic local transport ticket (which, just for reference, can cost between 200-300 euros per month for just one region in Germany). Only with a ticket that costs a maximum of one euro per day could these households be flexibly mobile within their financial limits.

The 9-euro ticket did not just make public transport more affordable; it has also made it easier. Germany has a system where almost every state has its own fare system. This makes buying tickets very complicated—if you use local trains, you often need two or three different tickets to get from A to B. “I could just get on a train and always be sure I had the right ticket,” a woman told me at one of the rallies that were organized to extend the 9-euro ticket.

Critics of the 9-euro ticket say it hasn’t really persuaded people to switch from cars to public transportation. However, recent studies show that 17 percent of 9-euro ticket users switched to public transportation in August from other modes. The Greenpeace study underlines this: Based on current data on the use of cars and public transport, the environmental organization compared various mobility options and investigated the conditions under which households would forego cars with internal combustion engines. Without the 9-euro ticket, these vehicles are more attractive in terms of price than local public transport.

Moreover, it could have been an even higher number had driving been made less attractive at the same time. Transport expert and professor Andreas Knie from the Social Science Research Center Berlin (WZB) says that in order to make public transport more attractive, it has to be more affordable and at the same time make driving less attractive. “It’s no surprise that people still prefer to use their cars, as long as parking in cities is free, for example,” he said.

While Germany is definitely a car-centric society and the car seems to be one of Germany’s most beloved material possessions due to its importance to the national economy and as a symbol of freedom and independence, the German car obsession seems to be reaching its limits. Only recently did the Council of Economic Experts issue its climate assessment of the transport sector. It failed the test. The expert panel concluded that with Wissing’s current plans, which include investments in electric car infrastructure, the transport sector will save only 14 million metric tons of CO₂ equivalents by 2030, leaving a gap of 261 million metric tons to the legal target set by the Climate Protection Act. If the transport sector continues at this rate, it would have to reduce emissions to zero in 2029.

Germany has one of the longest motorway networks worldwide today, ranking fifth after China, the United States, Canada, and Spain, and yet it still continues to build new roads, tearing down forests, destroying biodiverse habitats, and driving up CO2 traffic emissions. One example is the current debate about the planned highway through Berlin, the A100. In addition, although cars are generally less emission-intensive today, road traffic has increased due to larger, heavier, and more vehicles.

With the expiration of the 9-euro ticket, car subsidies are once again left untouched, while an unusually effective public transport subsidy is canceled. Despite its success, the government has allowed it to expire with only vague and unsatisfying plans for its continuation. For the German car industry, low prices through high subsidies and an attractive infrastructure can exist at the same time: Only for public transport are low prices a three-month exception.