A Doctor’s Mission: The Life and Work of Ernst Kisch

Kevin Ostoyich

Valparaiso University

Prof. Kevin Ostoyich was a Visiting Fellow at AICGS in summer 2018 and was previously a Visiting Fellow at AICGS in summer 2017. He is Professor of History at Valparaiso University, where he served as the chair of the history department from 2015 to 2019. He holds his B.A. from the University of Pennsylvania and his A.M. and Ph.D. from Harvard University. Prior to moving to Valparaiso, he taught at the University of Montana. He has served as a Research Associate at the Harvard Business School and an Erasmus Fellow at the University of Notre Dame. He currently is an associate of the Center for East Asian Studies of the University of Chicago, a board member of the Sino-Judaic Institute, and an inaugural member of the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum International Advisory Board. He has published on German migration, German-American history, and the history of the Shanghai Jews.

While at AICGS, Prof. Ostoyich conducted research on his project, “The Wounds of History, the Wounds of Today: The Shanghai Jews and the Morality of Refugee Crises.” The Shanghai Jews were refugees from Nazi Europe who found haven in Shanghai, and thus escaped the Holocaust. For this project Ostoyich has interviewed many former Shanghai Jewish refugees and has conducted research at the National Archives at College Park, MD, and United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. At Valparaiso University he co-teaches a course titled “Historical Theatre: The Shanghai Jews,” which fuses the disciplines of history and theatre. To date, students of the course have co-written and performed two original productions based on the history of the Shanghai Jewish refugee community: Knocking on the Doors of History: The Shanghai Jews and Shanghai Carousel: What Tomorrow Will Be. In addition to his work on the Shanghai Jews, he is currently working on projects pertaining to the experiences of ordinary Germans during the bombing of Bremen, German Catholic experiences in nineteenth-century Württemberg, German Catholic migration, and U.S.-German cultural diplomacy during the first half of the twentieth century.

Click here for an article by Ostoyich on the Shanghai Jews.

He is currently trying to interview as many former Shanghailanders as possible. If you would like to be interviewed or know someone who might want to be interviewed, please contact Professor Ostoyich at kevin.ostoyich@valpo.edu.

Read the stories of other Shanghai Jews

Dr. Ernst Kisch was an opera-loving Viennese physician who was imprisoned in Dachau and Buchenwald for being Jewish. Upon his release from Buchenwald, he journeyed to Shanghai, China. He soon took up a post at a Methodist mission hospital in Changchow, where he served throughout the Second World War. As the Communists swept through China in the following years, Kisch was forced to leave the country. He immigrated to the United States, where he worked in a hospital on Staten Island. He was forced to leave the United States due to visa issues and decided to join a mission hospital in South Korea, hoping eventually to return to China. He arrived in Kaesong near the 38th Parallel in the spring of 1950. Within weeks he was captured by the invading North Koreans. He lived in captivity for one year, during which time he was subjected to intense interrogations, a starvation diet, and a Death March. He tried to care for his fellow prisoners despite having little to no medical supplies. He died shortly after conducting a medical examination for one of the North Korean captors who had subjected Kisch and his fellow prisoners to much misery. Despite his mistreatment and weakened condition, Kisch stayed true to his mission of helping people across political borders.

Ernst Kisch was born in Vienna in 1892, the second of five children of Alfred and Emma Kisch (née Kraus). Alfred worked as a travelling representative for a paper mill. Ernst’s siblings were his older brother, Edgar (born in 1891); his younger brothers, Robert (born in 1893) and Walter (born in 1896); and his younger sister, Anny (born in 1894). According to Ernst’s brother Walter, the family was religious: “In our childhood we had a religion teacher who studied with us the Jewish history and as our parents were religious we learned all the prayers for the different Jewish holidays, the prayers for every day and of course Hebrew, readings and translating. On the Jewish holidays we went always with our father to the Temple where we had our places and he was very proud of his four sons who stayed with him during the service. The celebrating of this was always kept very high.”[1]

Walter described the Austria of his and his siblings’ childhood as being a place where anti-Semitism was tolerated, but Jews still “could live in peace.” He remembered that there were political parties that tried to stoke anti-Semitism among the populace and that Catholic priests were particularly anti-Jewish, often commenting in their sermons that the Jews were the killers of Jesus Christ. Such sentiment had a tangible effect on the Kisch household: A woman who worked as a domestic servant for a few years gave notice shortly before Easter one year, claiming that her priest had admonished that it was a sin to serve the Jewish people. Overall, Walter remembered anti-Semitism during his and his siblings’ childhood as taking hold “more in the lower class of people but of course in the high society it was more or less a struggle for a higher position in the society or in the political life.”[2]

The family was able to send their first two sons, Edgar and Ernst, to Gymnasium. Edgar was artistically inclined and eventually took up fashion design. Ernst decided to pursue a career in medicine and attended the medical school of the University of Vienna. The family could not afford Gymnasium for Robert and Walter, so they were sent to commercial school and Anny went to the Rudolfinerhaus to train to become a nurse.[3]

Immediately upon the outbreak of the First World War, Ernst was called to serve in the army. Eventually, he was transferred to a military hospital in Montenegro. The other Kisch children were also swept up into the war. Before the war, Edgar had taken a job as a dress designer in Paris. In 1915, Walter was conscripted into the army and Anny served in a war hospital as a nurse. After a few months, Walter was sent to fight on the Italian front, where he would participate in five of the twelve Isonzo battles between the Austro-Hungarian forces and the Italians. In 1916, Robert was conscripted into the army. However, due to a weak heart, he was sent to work as an office clerk in the war ministry. Eventually, Walter contracted typhus and was sent to various hospitals. Meanwhile, Ernst was evacuated in a submarine to the war port of Pula on the Istrian Peninsula (in modern-day Croatia) and eventually returned to Vienna in 1919 very sick. After the war Emma and Anny nursed both Ernst and Walter back to health in the Kisch home.

“Ernst Kisch might have been a world-famous figure, were it not for the extraordinary series of adversities that dogged his career.”

– Father Philip Crosbie

Ernst was a brilliant student of medicine. A Catholic priest, Father Philip Crosbie, later wrote of Ernst’s talents as a researcher: “Ernst Kisch might have been a world-famous figure, were it not for the extraordinary series of adversities that dogged his career. He passed brilliantly through the medical schools of his native Vienna in the days when those schools drew students from all over the world. While still a young intern, he made the first identification of a disease which makes war on the corpuscles of the blood, and which had till then remained mysterious. The skepticism of one of his professors towards youthful learning delayed the publication of his thesis. Meanwhile a German professor made and announced the same discovery, and the disease was called by his name. The name of Ernst Kisch remained unknown in the world of medicine.”[4]

Ernst had a lifelong love of music and often sang and played the piano. He enjoyed attending the opera, and when he established a practice in Vienna, he was able to afford prime seats in the Vienna Opera House. One of the most memorable musical events in the Kisch household was when Ernst organized a performance of Haydn’s Kindersinfonie to be played by the children for their mother, Emma, on her birthday with approximately fifty guests in attendance. One of the saddest moments in Ernst’s life also revolved around Emma—this being her death from a ruptured appendix in November 1928. Ernst never forgave himself for not being able to save his mother’s life—she simply had not told anyone of the pain she was suffering until it was too late.[5]

Ernst in the Third Reich

The Anschluss of March 1938 had an immediate impact on the Kisch family. Alfred was kicked out of the family apartment in which he had been residing simply due to the fact that a member of the SS wanted it. Although his children offered to take him in, he decided instead to get his own furnished room. Eventually, he would lose all of his belongings.[6]

On May 29, 1938—which happened to be Walter’s birthday—both Ernst and Walter were arrested by the Nazis. Walter had been on his way to work and was apprehended on the street. He was transported to a few police stations and eventually a school. Inside the school he encountered Ernst. Walter remembered Ernst “with tears in his eyes [congratulated] me [for] my birthday and said it is not a nice birthday present what you got, but God will help us and our family.” Two days after having been nabbed by the Nazis, Walter and Ernst were sent to Dachau on an eighteen-hour train ride. Walter later noted, “It is better not to remember how this 18 hours travelling time was [spent].” While imprisoned in Dachau, Walter and Ernst were put to work building streets and forced to wear striped uniforms with a yellow star mixed with a red star to identify them as Jewish political prisoners.[7]

On September 23, 1938, they were given new uniforms, marched to a train, and sent off to the Buchenwald concentration camp outside Weimar, Germany. Walter described the conditions that he and Ernst had to endure in Buchenwald: “This place was dirty and looked terrible. 40,000 prisoners. A very big place absolutely empty surrounded by wire fences and watchtowers and on one side barracks four in one row and six rows behind. No W.C. [rather] open latrines in the sideways of the barracks. During the night an open barrel stand inside the entrance. I slept with my brother in one bed in a room with 120 other inmates. I don’t want to talk [about] what all happened there […], it was really terrible and best to try to forget.”[8]

In Buchenwald the brothers had to work in freezing conditions. As a result, black spots started to appear on Walter’s hands. When Ernst noticed this was happening to his brother, he informed Walter that he would have to operate in order to prevent him from succumbing to blood poisoning. What followed must have been nothing short of horrific. Because Jews were not allowed to receive medical care in the camp infirmary, Ernst had to perform the surgery on Walter without anesthetic using a pen knife and a pair of nail scissors. While other prisoners held Walter down to a chair, Ernst dug out the dead flesh. When Ernst finished, the prisoners took Walter, who by this time had lost consciousness, to his bed. The next morning the prisoners were awoken at 3 a.m. Despite what he had been through the previous day, Walter was not exempted from work. Later that day the same tell-tale black spots started to appear on Ernst’s hands. Given that Ernst had provided medical care to the block leader—who was not Jewish—the latter gave Ernst his coat with a green triangle—the camp symbol for “criminals”—rather than the yellow and red Jewish star affixed to it, and escorted Ernst to the infirmary. There Ernst was admitted for surgery, which was conducted with anesthetic. Afterward he was exempted from work for three days. Nevertheless, Ernst was still forced to walk around outside during those three days and became extremely ill. This time it was Walter’s turn to look after Ernst. Walter remembered: “We hoped and prayed to keep our strength to overcome everything.”[9]

In February 1939, Walter’s camp number was called along with those of a few other prisoners. It turned out that Walter and these men were to be released. Walter’s wife, Grete had been able to secure a visa from the Chinese consulate.[10] Walter was given twenty-one days to leave the Greater German Reich; otherwise, he would be sent back to a concentration camp. He headed for Shanghai as a visa was not required for entry into the city. Ernst stayed in Buchenwald for at least another two months.[11] Ernst was most likely released as a result of the efforts of Walter’s wife, Grete. In April 1938, Walter received a letter in Shanghai from Ernst notifying him that he too was setting out on the journey and in May, Ernst arrived. Walter and Ernst were able to go to Shanghai because Alfred had been able to secure money for their tickets from Mr. Buhrman of the Buhrman’s Papier Groothandel, N.V., a Dutch paper company located in Amsterdam.[12] Walter decided to stay in Shanghai and started to try to get his wife, Grete, and their young son, Eric, to make the journey to Shanghai. Grete was looking after her parents in Vienna. After her father passed away in January 1940, and her mother secured sponsorship from her son for entry into Australia, Grete, her mother, and Eric made the journey to Shanghai, arriving in February 1940.[13] Grete remembered that upon her arrival in Shanghai, Ernst informed her that Walter was having an affair with a married woman. Although he and his brother had shared many horrific experiences together in Dachau and Buchenwald, it seems Ernst did not condone his brother’s marital infidelity to the woman who most likely secured his release. Naturally, Grete was terribly upset.[14]

The War Years in China

Ernst worked for a Catholic hospital in Shanghai.[15] He decided not to stay in Shanghai, however, and moved on to Changchow (modern-day Zhangzhou) after meeting a Dr. Roman Zieher, who introduced him to the idea of working for the Methodist Stephenson Memorial Hospital. Ernst took up the challenge to administer care to the Chinese.[16]

In his brief biography of Ernst Kisch, Thoburn T. Brumbaugh, a member of the Board of Missions of the United Methodist Church for Japan, Korea, and the Philippines,[17] described Ernst’s actions on behalf of the mission hospital in Changchow. In his narrative he explains that as Ernst worked for the hospital, he gradually grew closer to the Methodist faith. Music proved instrumental for this religious journey. Brumbaugh explains: “Ernst Kisch himself was devout in observing all the feast and fast days of his own faith, but he also liked to take part in the Christian services. He became the regular organist in chapel.”[18] Brumbaugh reports that the “hymns and ceremonies of the church appealed to [Ernst] greatly.”[19] As Ernst became more involved in the church services, he even “consented to be godfather to the child of a Chinese nurse and her husband, a pharmacist at the hospital. After the baby’s baptism, [Ernst] began to talk about helping to establish a kindergarten in Changchow for the Christian training of his godchild and other children.”[20]

Growing up in Shanghai, Eric viewed his Uncle Ernst as a somewhat mythical figure who would show up wearing a pith helmet and carrying exotic fruits and eggs—rare items in wartime Shanghai.

The running of the hospital became more difficult after the attack on Pearl Harbor. American workers had to leave. Eventually, only Ernst and Dr. Zieher remained “to work with the Chinese staff in serving all the stricken in both the rural and urban areas around Changchow.”[21]

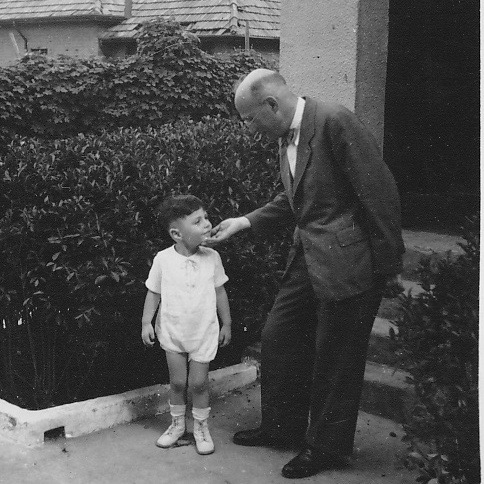

Ernst occasionally returned to Shanghai to visit Walter, Grete, and Eric. Growing up in Shanghai, Eric viewed his Uncle Ernst as a somewhat mythical figure who would show up wearing a pith helmet and carrying exotic fruits and eggs—rare items in wartime Shanghai.[22] Toward the end of the Second World War, Ernst visited after a long hiatus and said that Dr. Zieher had left for the British army and all the American doctors and nurses had left as well, leaving Ernst and a Chinese doctor to look after the mission hospital. In the summer of 1946, Walter, Grete, and Eric left Shanghai for Australia. Walter tried to convince Ernst to join them in Australia, but Ernst refused because he would not be able to work there as a doctor.[23]

Brumbaugh explains that the challenges of running the hospital did not end with the conclusion of the Second World War: “[For] Ernst and the hospital the days of trial were not yet over. After the withdrawal of the Japanese troops, a new struggle began between the forces of the Chinese Republic under Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and the Chinese Communists who were trying to wrest control from him. Even greater confusion and disorder afflicted the country. Despite efforts of the United States and other powers to reconcile differences between the two factions, the conflict between the opposing forces continued.”[24]

An Interlude in the U.S. and Ernst’s Fateful Return to Asia

As the Communists swept through the country, working at the mission hospital was no longer a viable option for Ernst. He decided to go to the United States.[25] Ernst arrived in New York and started to work at Seaview Hospital on Staten Island.[26] It was in the United States in March 1950 that Ernst was baptized. The ceremony took place in the Washington Square Methodist Church under the direction of Rev. Philip S. Waters.[27] Ernst was unable to extend his visa and was warned that he would be deported to Austria. According to Walter, Ernst resolved never to return to Austria, and decided instead to go back to Asia.[28] According to Brumbaugh, one reason Ernst opted for Asia was that Ernst wanted to find the boy for whom he had acted as godfather. China was not an option, so Ernst decided to take up a post in the Ivey Hospital of the Methodist mission in Kaesong, South Korea.[29] He arrived in May or June 1950 and decided to stay with the young newlywed couple of Larry and Frances Zellers. The Zellers were both teachers attached to the Methodist mission in Kaesong. Zellers remembered Kisch telling him that he volunteered “to work in Ivey Hospital in Kaesong, ‘to be near my beloved China.’”[30] Zellers remembered that to this end, “Kisch had brought many trunks full of gifts for his friends in China and stored them in our house. ‘You wait,’ he used to say. ‘One day I will return to China.’”[31]

According to Zellers, Ernst had actually been supposed to live with a different family but had opted to stay with them because he wanted to be around their youthful laughter. Zellers later wrote that Ernst had told him, “‘Larry, I wanted to live with you and Frances because I knew that I would have more fun there. You were a young couple and were always laughing.’” Zellers added, “I didn’t have to be reminded that as a Jewish survivor of Buchenwald and Dachau, he deserved all the laughter he could find.”[32]

“I didn’t have to be reminded that as a Jewish survivor of Buchenwald and Dachau, he deserved all the laughter he could find.”

–Larry Zellers

Ernst figures prominently in the memoir of Zellers (published in 1991) as well as those of Catholic priest Father Philip Crosbie of Australia (published in 1953) and the captured war correspondent of The Observer, Philip Deane (published in 1953). From these memoirs as well as letters written by the missionary Nellie Dyer to Ernst’s brother, Robert, in July 1952, and Philip Deane to Ernst’s brother, Walter, in May 1953, we can piece together Ernst’s last year of life.[33]

The Final Year

On the morning of June 25, the North Koreans crossed the 38th Parallel and quickly enveloped Kaesong.[34] Larry and Frances had earlier attended a wedding in Seoul, where Frances got sick and was on doctor’s orders to stay in bed. Larry’s friend Kris Jensen decided to accompany Larry from Seoul to Kaesong and stay for the remainder of the weekend and then return to Seoul on Monday. Thus, when the North Koreans moved into Kaesong, Larry Zellers, Kris Jensen, and Ernst Kisch were in the Zellers’ house.[35]

The three laid low for a few days as the North Koreans took over Kaesong. Then they went to the Ivey Hospital to look after patients. Ernst said that the North Korean soldiers would not let him touch them. According to Zellers, Ernst said, “Even the Nazi SS sought out and accepted my medical skills when I was in Buchenwald and Dachau. These men have been poisoned against us. They will not permit me to help them.”[36] On June 29, Zellers, Jensen, and Kisch went to the house of three American women missionaries: Nellie Dyer, Bertha Smith, and Helen Rosser.[37]

According to Nellie Dyer, “On the morning of June 29 [the three] men came over to the missionary home where I lived with Miss Smith and Miss Rosser. Tanks had moved in very near their house and they thought it best to leave home. They spent the day with us. After supper a North Korean Communist came and told us to go down and pay our respects to the new commandant. He promised to bring us back soon but we were never allowed to return.”[38] The six missionaries reported to the authorities in a former prison in the middle of the city. Thus started their long imprisonment. According to Zellers, the missionaries were accused of being spies and exploiters of the Korean people.[39] They were interrogated all night and the next morning were put into a cell of “thirty men and women.”[40] That day they were subjected to more interrogations. On July 1, 1950, they were sent to the headquarters of the National Internal Security in Pyongyang. There the three men were separated from the three women and put into a death cell. Zellers explained, “After being placed in the cell, Kris, Dr. Kisch, and I were instructed not to talk and to go to sleep at once. We would be required to arise at six and retire at ten o’clock. During the day, we would be given three meals and allowed to use the toilet in the corner three times. Otherwise, we were to sit cross-legged and remain perfectly still in the middle of the room, facing the back wall. Except for the three small meals and bathroom calls, we had to sit still for sixteen hours each day without any back support. A powerful electric light burned continually overhead.”[41]

Zellers was shown the place where prisoners were executed. From that time forward the three men were subjected to intense interrogations and heard the gun shots of executions at “any time of the day or night.”[42] Zellers wrote: “From somewhere outside the cellblock came the sounds of gunfire, one or two shots at a time in perhaps five distinct groups. I did not immediately connect those sounds with what was apparently occurring. Then I suddenly realized the truth: those ‘bad men’ that the guard had told me about in the latrine were being executed. For some time I was too stunned by this startling revelation to react in any way. In our very constrained environment we were not allowed to communicate with each other. I turned my head very slowly to see whether Kris and Dr. Kisch had heard the gunfire. In the periphery of my vision I was able to see that Kris was looking at me. His face was grave. Dr. Kisch sat very still with head bowed. They must both have been aware of the tragic situation.”[43]

Zellers remembered the interrogators informing him that they would kill him as well. It is likely Ernst was told the same.

They were each taken at various times to be interrogated. Zellers described the interrogators that he, Ernst, and Jensen faced: “They had the training to make us pay dearly for thoughts and attitudes that were not ‘correct.’ These people felt that they were doing us a favor when they caused us all forms of deprivation: loss of freedom, controlled starvation, controlled fatigue, controlled fear, controlled confusion, confinement. The purpose was to assist us in learning the ‘truth,’ according to their definition of it.”[44]

Zellers noted that Ernst, drawing from his experience at Dachau and Buchenwald, counselled Jensen and Zellers that the interrogators had already decided their fate and nothing they did or said in the interrogations would change this fate. At first Zellers believed Ernst and says in his memoir that this was actually psychologically comforting at first—for otherwise the pressure of thinking one’s fate actually depended on one’s performance during the constant interrogations would have been too much to bear. Over time, however, as the interrogators dangled some hope in front of Zellers, he started to doubt Ernst’s advice.[45]

Due to bombing in Pyongyang,[46] the missionaries were moved during the second week of July.[47] They were taken to a schoolhouse where they were joined by other prisoners. They stayed there for six weeks and were subjected to more interrogations.[48] The number of prisoners grew to about fifty at this time and they came from countries all over the world.[49] It was there that they were joined by the correspondent of the Observer, Philip Deane, who later published accounts of his imprisonment.[50]

Deane wrote how he first encountered Kisch. It was about a week after being shot in the hand and the thigh, taken prisoner, and then marched for many miles on mountainous terrain, that Deane was finally allowed by his North Korean captors to receive medical attention for his wounds. He was cared for by Ernst, who squeezed out the bullets, removed as much of the infection as possible, and packed the wounds “with some sulphanilamide powder which a French chargé d’affaires had somehow managed to bring with him into internment.”[51]

It was also in the schoolhouse that they were joined by the Australian Catholic priest, Father Philip Crosbie, who also later wrote about his captivity.[52] On September 5, 1950, they were moved—again due to American bombing.[53] They were put on a train to Manpo with over 500 American military prisoners of war.[54] Regarding the American POWs, Zellers wrote, “Later we learned that the POWs numbered 726 when they left Pyongyang in the fall of 1950. Another thirty prisoners joined them later in the year. When we last saw them on October 10, 1951—more than twelve months later—their numbers had dwindled to 292[.]”[55]

The prisoners arrived in Manpo on September 11, 1950 and were housed in “a compound that had been an old quarantine station during the Japanese occupation of Korea.”[56] Zellers explained, “We were relatively well looked after at Manpo. Thanks to the abundance of very nourishing food, the relatively freer regime of the army (as opposed to the prison system that we had known before), the adequate accommodations, the medical attention, the lack of interrogations, and the provisions for bathing, our stay was not too bad.”[57]

In October they moved along the Yalu River to a school building in Kosan.[58] In late October they again moved, this time by foot to Jui-am-nee, but then returned to Kosan. There they were introduced to a new commanding officer: A major they referred to as “The Tiger.” Conditions under The Tiger took a decided turn for the worse.[59] The Tiger set the prisoners off on a Death March. When learning that they would have to march, some prisoners voiced concerns that they would die. The Tiger’s response was “Then let them march till they die. That is a military order.”[60]

Philip Deane wrote about how The Tiger ordered the Death March: “‘I,’ said The Tiger, pulling down an epaulette in a gesture we were to know well, ‘am a major of the People’s Army. I am to be obeyed. I have authority to make you obey. You will march to another place now.”[61]

Zellers described the Death March as follows: “With The Tiger as our guide, we were now moving into an existence in which the most ordinary, decent human emotions would evaporate in the face of the gun; raw power would replace conscience, and the man with the gun would become all things to all men.”[62] During the Death March the temperature was starting to fall and most of the prisoners were only wearing summer clothes. Zellers explained the group consisted of “such a ragtag collection of military prisoners, diplomats, journalists, very old missionaries, women, young children, that only a madman would even dream of conducting a march under such conditions.”[63]

Early in the Death March, The Tiger demonstrated just what sort of leader he was when he threatened to kill American POW group leaders for allowing certain men in their group to drop out due to exhaustion. When told that North Korean guards had allowed this, The Tiger still insisted on punishment. He decided to shoot the leader of the group who had let the most men fall out during the day: Lt. Cordus H. Thornton. In front of the prisoners, The Tiger immediately put on a show trial with the North Korean soldiers acting as the “jury.” After this hasty show, The Tiger took out his pistol and shot Lt. Thornton in the back of the head.[64]

As the group marched, they had to come up with systems in which the stronger tried to help the weaker prisoners continue marching. Given that many of the marchers were injured, extremely frail, and/or elderly, this usually only prolonged the inevitable.[65]

They were subjected to the elements day and night and had very little food. The Tiger kept them marching day after day at an unrelenting pace. The Tiger claimed that the sick and the wounded who were unable to go on were going to be sent to the “People’s Hospital.”[66] The prisoners soon found out what he had meant by the “People’s Hospital” when they heard gun shots from the North Korean guards who stayed back with those prisoners who could no longer march. The Tiger had ordered that all dog tags be confiscated and that there be no burial mounds left in order to hide his crimes.[67]

Zellers remembered one time when he was marching with Ernst; the two spoke about the ability of people to sleep while marching. Zellers apparently was capable of this. Ernst said that at one point, Zellers had started to “stray off the road” while marching asleep.[68]

On most nights the prisoners were forced to sleep out in the open. Responding to complaints about this, The Tiger cruelly forced the approximately 800 prisoners into a small schoolhouse one night. There was not enough space for anyone to lay down. Instead everyone had to squat.[69]

As they marched the next day, many of the missionaries and POWs were struggling. Zellers explained, “As other groups of two fell behind—one stronger, one weaker, but together trying to trade a little time in exchange for a life—each couple was assigned a guard, and the decision was his whether to tolerate the delay. Many did not. The sound of the gun was heard in the gathering darkness.”[70]

Deane described the horrors of the marching: “The eighty-two-year-old French missionary was being carried by Mgr. Thomas Quinlan. Miss Nellie Dyer, an American Methodist missionary, was carrying Sister Mary Clare, the Anglican nun, in her arms. Father Charles Hunt, an Anglican missionary, suffering from gout, was being dragged along by his companions. Commissioner Herbert Lord of the Salvation Army, the column’s official interpreter, had tied a rope around the waist of Madame Funderat—a seventy-year-old White Russian—and was pulling her along. Two White Russian women walked with crying, cold, hungry babies on their backs, holding their other young children by the hand. The children who were not being carried had to trot because the pace was too quick for their gait. Two Carmelite nuns were coughing up blood. They were shod in rough wooden sandals they had made themselves. Norman Owen, pro-consul at the British Legation, Seoul, had as his only footwear Father Hunt’s chasuble, divided in two with a half for each foot. The septuagenarian French fathers, obliged to stop because of their dysentery, were egged on by the guards, who fired off their rifles near the old men’s ears.”[71]

Zellers explained that the worst part of the Death March was when it started to snow. The Tiger kept the march at a cruel fast pace because he was concerned that their destination would be closed off to them due to the snow. As the grade of their path started to rise, the snow became more and more of a problem.[72] During this day Zellers marched with Ernst for a while because Ernst was walking with difficulty.[73] Eventually, though, Zellers switched to helping a Catholic nun.[74]

On this day many prisoners who could not go on were executed—their blood turned the snow red.[75] The guards threw corpses over the side of the mountain they were climbing. Zellers described coming upon those who could not go on: “There are no words. Feelings don’t even have a name. Soon we came upon other young men who could not go any farther. They were awaiting execution as soon as our group had passed them. I could tell by looking into their eyes that they knew what was coming. I looked back a second time at the sound of another shot to behold the same wretched scene as before. I didn’t look back anymore.”[76]

One of the men who could not go on and awaited death from a North Korean guard’s bullet sang “God Bless America” with tears streaming down his face.[77]

Toward the end of the Death March, Ernst was ordered to sign a document that stated the cause of death of the people who had died on the march as enteritis. According to Zellers, Ernst claimed he had been forced to do the same for the Nazis in Dachau and Buchenwald.[78] The Death March ended when they arrived in Chunggangjin on November 8, 1950. The group had started marching on October 31 and had covered approximately 110 to 120 miles during the Death March.[79] Their ordeal was far from over, though, as The Tiger decided the prisoners now had to perform calisthenics outside in the cold.[80] They then marched from Chunggangjin to Hanjang-ni.[81] People continued to die from the lasting effects of the Death March and the “starvation diet.”[82] Finally, at the end of December 1950, The Tiger was removed as their commandant. Zellers summed up The Tiger as follows: “What is there to be said about The Tiger? He took life. He caused pain. He destroyed dignity. Under his control we lost our respect and our pride of membership in the human family for a time. Beyond that, he took from us only what we had ceased to value.”[83]

The new commandant came in January 1951.[84] That month, some of the prisoners started to show signs of beriberi due to vitamin deficiency. The North Koreans treated this with iodine and aspirin, much to Ernst’s dismay. According to Zellers, Ernst said, “Can you imagine treating a vitamin deficiency disease with iodine and aspirin?” The prisoners found that the best remedy against beriberi was soybeans.[85]

They left Hanjang-ni on March 29, 1951.[86] Behind them they left “the bodies of 200 to 250 people, most without proper burial.”[87] They moved to “an old Japanese army camp from pre-World War II days” in An-dong.[88] It was in An-dong that the civilian prisoners got to interact with the American POWs.[89] In An-dong there were communal gatherings with songs. At these gatherings, Ernst would play classical music on an out-of-tune piano.[90] On May 10, 1951, the civilian prisoners were once again separated from the POWs because the North Koreans thought the civilians were impeding their work of trying to indoctrinate the POWs to Communism.[91]

Zellers explained that “The political officer of the camp as well as the deputy commandant” was known to the prisoners as the Mystery Man.[92] Mystery Man took an interest in Ernst and the two would converse through a translator.[93] Mystery Man asked Ernst to perform a medical physical of him. This Ernst did.[94] Shortly afterward Ernst’s health started to decline. He was particularly afflicted by diarrhea. The missionary Nellie Dyer explained that Ernst’s body broke down due to the diet: “Dr. Kisch had great difficulty with the diet. We had corn, millet, and beans all of which he said he could not digest. He had great trouble with diarrhea or dysentery. His body could take care of rice but we did not have enough rice to live on it solely. He suffered from beriberi because of the poor diet and grew weaker and weaker.”[95] Father Crosbie and Zellers tried to help out by trading part of their rice portions for Ernst’s millet portions so that Ernst could have more of the rice. Eventually, Mystery Man had Ernst moved to the main camp where the POWs were so that Ernst could be put under the care of the POW doctor, Dr. Alexander Boysen.[96]

Dyer went to see Ernst on June 26, 1951. She later wrote, “He said to me then that he knew he could not go home although he wanted to go and that he had thought to give me some instructions about his will. I urged him to keep fighting for his life and not to give up. Perhaps I should have told him then to give me any farewell messages he had but I did not realize that death was so near and I did not want to encourage him in his feeling that he would not live. That was the last time I talked to him.”[97]

Zellers wrote, “We saw Dr. Kisch a few times […] on ration detail but he seemed to be going downhill steadily. He died near midnight on June 28, 1951, one year after his arrest with me in Kaesong.”[98]

“We knew at least some of the bitterness he had tasted in life, and there was fervor in our prayer when the time came to lay his tired, worn body down: ‘Eternal rest grant unto him, O Lord, and let perpetual light shine upon him.’”

– Father Crosbie

Ernst’s death had a significant impact on his fellow prisoners. Zellers wrote, “the death of Dr. Kisch was a great personal loss to me.”[99] Father Crosbie remembered, “We knew at least some of the bitterness he had tasted in life, and there was fervor in our prayer when the time came to lay his tired, worn body down: ‘Eternal rest grant unto him, O Lord, and let perpetual light shine upon him.’”[100] Deane later sent a letter to Ernst’s brother, Walter, in which he wrote, “I am sorry, deeply sorry, that I have come out without him. He is buried in an unmarked grave near Chung Kang Djin in North Korea. He lies in good company: Near him we buried many good men.”[101]

The prisoners most likely buried Ernst facing south. Zellers explained that they tended to bury everyone who was not Russian in the direction of the nearest non-Communist land. (They buried the Russians facing east.)[102] When Ernst was buried in North Korea, he had already been preceded in death by his father, Alfred, who had died in Theresienstadt in 1942; his older brother, Edgar, and Edgar’s wife, Edith, who both were killed on May 28, 1943, in Sobibor; his sister Anny, who died in Ravensbrück in 1942, Anny’s husband, Richard Taub, who died in Auschwitz, and Anny’s and Richard’s children, Charlotte, Arnold, and Emilie, who were killed in Auschwitz in 1944. Only Ernst’s brother Robert and Robert’s wife, Louise (Robert having escaped from Theresienstadt and having joined the Russian army as it took over Czechoslovakia), Edgar’s and Edith’s son Peter (who had been rescued through a Kindertransport to England), and Walter, Grete, and Eric were still alive.[103]

Who Was Ernst Kisch?

Ernst Kisch was clearly a remarkable doctor. His fellow captives remembered him having tried his best to look after his fellow prisoners and often being frustrated by having to witness the prisoners die one-by-one of ailments that could have been treated if he had had the necessary medicine. The degree to which Ernst could act in his capacity as a doctor ultimately varied based on where they were and who was in charge of them at any given time. Dyer wrote, “Where we were prisoners, [Ernst] was at some periods given some drugs and allowed to administer them to the other prisoners. Part of the time he was not recognized as a doctor. He did save the lives of some people and gave help to many others. He was always very much interested in my health as I was another member of the Methodist Mission and I greatly appreciate the advice and help he gave me.”[104] Father Crosbie, who reported on Ernst’s major research discovery as a medical student, remembered Ernst’s often frustrated attempts to get supplies for his fellow prisoners: He remembers when they were in the Pyongyang camp: “Dr. Kisch asked for medical supplies to treat the sick. A guard had him write out a long list of what he required. A month later that same guard was going through his pockets in search of something else, and out came that same list. Again, we had visits from time to time from a Korean doctor and his assistants, who took notes of the medical condition of the prisoners and promised to send remedies next day. The remedies regularly failed to arrive.”[105]

Crosbie remembers Ernst being much more successful when they were in Manpo. He noted that in Manpo there was a Korean doctor who visited twice a week. “It was by his efforts that we received a stock of common drugs, the first and last issue of medical supplies our captors gave us.”[106]

In addition to Ernst there were two trained nurses: Mother Eugénie and Helen Rosser “but hitherto their efforts to help our sick had been gravely hampered by the lack of even the simplest medical supplies.” With the supplies provided by the Korean doctor, Ernst could run a daily clinic with Rosser as his assistant. Crosbie described the routine: “Every afternoon about four o’clock a bald, bespectacled little man appeared at the door of an unoccupied room, and called in a high-pitched voice: ‘Clinic time!’ Ernst Kisch, M.D. […] was ready to see patients.”[107] According to Crosbie, “The children in our camp had precious few distractions, but this daily announcement was one of them. They took up the cry ‘Clinic time!’ and soon became so perfect in their mimicry that the doctor seemed to be repeating himself.”[108]

After Manpo, Ernst never was afforded such an opportunity to administer care to that degree. Dyer remembered, however, that toward the very end of Ernst’s life, his skills were recognized by the captors: “His professional skill was appreciated by the Korean who was called a “Doctor” and he asked him to help him. For the last weeks of his life he spent much time lying on a bench in the doctor’s office giving advice to the Korean medical man as he prescribed for the American soldiers who were held prisoners with us.”[109]

When reflecting on Ernst, Deane wrote: “During the captivity his greatest hardship, he said, was not being allowed to use his knowledge in curing anyone.”[110]

“During the captivity his greatest hardship, he said, was not being allowed to use his knowledge in curing anyone.”

– Philip Deane

Crosbie remembered one of their number, a mining engineer from Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, Walter Eltringham, having declared that Ernst had no bedside manner.[111] Crosbie apparently agreed with Eltringham’s assessment, saying “Dr. Kisch was a peppery little man, and a bedside manner would have choked him. And each [Kisch and Eltringham], in his way, was a great man.”[112] Crosbie’s characterization of Ernst seems to go along with Zellers’ memory of a man who “always spoke his mind.”[113]

And then there was the music. Ernst Kisch was a great lover of music. Classical music was ever present in this doctor’s life, from organizing the family performance of Haydn’s Kindersinfonie for his mother to playing organ for the Methodist services in China. Even in North Korea, Ernst managed to serve others with the medicine of music. Amazingly, Ernst kept his fellow captives entertained by giving complete, one-man performances of the operas he had attended in Vienna. He would sing the arias, hum the music, and narrate the plot all in complete darkness. Zellers explained, “One day I asked Dr. Kisch if he would tell us the story of some well-known opera; he must have known all of them almost by heart. He agreed but added that he wanted to wait until after dark; later he told us that he was too embarrassed to sing opera if we could see his face. It was an arrangement that worked out in a wonderful way. Night after night we were treated to the sounds of the arias of famous operas; [Wagner’s] Tristan and Isolde, Bizet’s Carmen, and [Gounod’s] Faust seemed to be his favorites. He would include narrations between the arias to keep us abreast of the story.”[114]

Father Crosbie summed up Ernst in the following musical terms: “A true Viennese, he loved music, and was himself an accomplished pianist. For years he would not let a week pass without visiting the Vienna Opera House, and he was familiar with every opera worth knowing. He could tell the story, recite the German words, and hum the melodies. He often entertained a group of us with recitals of this kind as we lay in the dark on long winter evenings. On these occasions he was transported back in memory to the old Vienna he loved so well, the Vienna that was still basking in the sunshine of royal patronage. But those excursions left him sad and wistful, reminding him not merely of his happiness, but also of the bitterness of its shattering.”[115]

Although Ernst and the other civilian prisoners were often kept separate from the American POWs, his life left a mark on at least one of their number. In 2010, “Tiger Survivor” Shorty Estabrook wrote about his experiences with Ernst for the Ex-POW Bulletin. As Estabrook covered Ernst’s brief interlude in the United States, he wrote: “Doctor Kisch, a man who had so much to give to mankind and a man who did not demand much from society except the chance to serve, was refused admittance into the United States of America. My country did that to this wonderful person.” Estabrook recounted how the civilians and POW group, who collectively became known as the “Tiger Survivors,” were subjected to the Death March. According to Estabrook’s memory, “89 people were shot along the way” and that 222 died during the winter at Hanjang-ni. Estabrook continued that “At An Dong there was a hospital set up. At that place I was cooking for the hospital group and would walk with Doctor Kisch on some days. He had become weak and was in the hospital himself. He was suffering from many things and had become very frail and weighed less than 100 pounds. He looked like some of the survivors of Hitler’s death camps.” Estabrook concluded, “It is most sad that his passing had to go unnoticed. That is why I am writing to you now. Hopefully you can pass this on to all your friends and by so doing his memory will be kept alive. I am not Jewish but I loved this dear man who touched my life during those impossible days that left 58% of our group bleaching on the nearby hills. I am now crying and will close.”[116]

Ernst Kisch left a mark on his nephew, Eric Kisch, as well. Eric is an octogenarian and retired market researcher who, for the last fourteen years, has hosted the weekly broadcast Musical Passions for Cleveland’s classical music station, WCLV 104.9.[117] Like his uncle before him, Eric likes to spread the wonder and joy of classical music, including opera, to others—although he will not sing arias, regardless of how dark the night. When informed that this article was being written about his uncle, Eric wrote, “You are resurrecting a man I barely knew as a small child and keeping the flame of his life and work alive. For this I and my family will be eternally grateful.” One can only hope that the flame of Ernst Kisch’s life will continue to burn. May his life and work inspire us all to stay noble and resolute in the face of barbarity and hate. May his music and medicine sooth and heal this wounded world.

[1] Walter Kisch Letter to Thoburn T. Brumbaugh, August 1, 1967. (Private Collection of Eric Kisch).

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Philip Crosbie, Three Winters Cold, (Dublin: Browne & Nolan, 1955), 103.

[5] Walter Kisch Letter to Thoburn T. Brumbaugh.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Unpublished memoir, “Grete Gabler’s Story.” (Private Collection of Eric Kisch.)

[11] Ibid.

[12] On September 8, 1958, Walter Kisch sent a check to Buhrman’s Papier Goothandel, N.V. of hfl. 715.30 in order to pay back what Mr. Buhrman (who was then deceased) had provided to Alfred Kisch for Walter’s passage. At the closing of the letter accompanying the check, Walter wrote that he would try to pay back the money for his deceased brother, Ernst, as well, when he could do so. Copy of Walter Letter to the “Herren of Buhrman’s Papier Groothandel, N.V.,” September 8, 1958. (Private collection of Eric Kisch).

[13] Dates supplied by Eric Kisch in e-mail correspondence with the author.

[14] “Grete Gabler’s Story.”

[15] Thoburn T. Brumbaugh, My Marks and Scars I Carry: The Story of Ernst Kisch, 38.

[16] Walter Kisch Letter to Thoburn T. Brumbaugh and Thoburn T. Brumbaugh, My Marks and Scars I Carry, 38.

[17] https://www.nytimes.com/1974/05/17/archives/rev-t-t-brumbaugh.html. (Accessed December 19, 2018.)

[18] Brumbaugh, My Marks and Scars I Carry, 42.

[19] Ibid., 43.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid., 44.

[22] Interview of Eric Kisch by Kevin Ostoyich, September 9, 2017.

[23] Walter Kisch Letter to Thoburn T. Brumbaugh.

[24] Brumbaugh, My Marks and Scars I Carry, 45.

[25] Ibid., 46.

[26] Ibid., 47.

[27] Ibid., 49.

[28] Walter Kisch Letter to Thoburn T. Brumbaugh.

[29] Brumbaugh, My Marks and Scars I Carry, 47-48.

[30] Zellers uses “Ivy” throughout his text. I have corrected this to Ivey. Brumbaugh uses “Ivey” in his text.

[31] Larry Zellers, In Enemy Hands: A Prisoner in North Korea (Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 1991), 12.

[32] Zellers, In Enemy Hands, 175.

[33] Nellie Dyer Letter to Robert Kisch, July 2, 1953 and Philip Deane Letter to Walter Kisch, May 5, 1953.

[34] The various prisoners used different spellings for the towns they encountered. For the main text, the author has gone with the spellings used by Lawrence Zellers. Within quotations, the spellings of the respective authors have been preserved.

[35] Frances safely escaped Korea. Zellers, In Enemy Hands, 49.

[36] Ibid., 3.

[37] Ibid., 10 and 12-13.

[38] Nellie Dyer Letter to Robert Kisch, July 2, 1953.

[39] Zellers, In Enemy Hands, 15.

[40] Ibid., 17.

[41] Ibid., 25-26.

[42] Ibid., 27.

[43] Ibid., 27.

[44] Ibid., 33-34.

[45] Ibid., 42.

[46] Ibid., 49.

[47] Ibid., 50.

[48] Ibid., 54.

[49] Ibid., 56.

[50] Ibid., Philip Deane (Philippe Gigantès) published I Was Captive in Korea (New York: Norton, 1953). The book also appeared as Captive in Korea (London: Hamisch Hamilton, 1953). He revisited the history in I Should Have Died (New York: Atheneum, 1977).

[51] Philip Deane, Captive in Korea, 38. (Note: The version of the book cited in this article is Captive in Korea (London: Digit Books series of Norton Watson, 1958).). Larry Zellers’ account of Kisch caring for Deane: Zellers, In Enemy Hands, 57.

[52] Zellers, In Enemy Hands, 60.

[53] Ibid., 57.

[54] Ibid., 59.

[55] Ibid., 61.

[56] Ibid., 66.

[57] Ibid., 74.

[58] Ibid., 75.

[59] Ibid., 84-85.

[60] Ibid., 85.

[61] Deane, Captive in Korea, 71.

[62] Zellers, In Enemy Hands, 86.

[63] Ibid., 88.

[64] Ibid., 89-91. Philip Deane’s description of Thornton’s execution by The Tiger: Deane, Captive in Korea, 72-73.

[65] Zellers, In Enemy Hands, 100.

[66] Ibid., 99-100.

[67] Ibid., 102.

[68] Ibid., 100.

[69] Ibid., 102.

[70] Ibid., 108.

[71] Deane, Captive in Korea, 71-72.

[72] Zellers, In Enemy Hands, 111.

[73] Ibid.

[74] Ibid., 112.

[75] Ibid.

[76] Ibid., 113.

[77] Ibid.

[78] Ibid., 118.

[79] Ibid.

[80] Ibid., 120.

[81] Ibid., 123.

[82] Ibid., 126.

[83] Ibid., 143.

[84] Ibid., 144.

[85] Ibid., 148.

[86] Ibid., 154.

[87] Ibid., 155.

[88] Ibid., 156.

[89] Ibid., 158.

[90] Ibid., 166.

[91] Ibid., 169-171.

[92] Ibid., 174.

[93] Ibid., 171.

[94] Ibid., 172.

[95] Nellie Dyer Letter to Robert Kisch, July 2, 1953.

[96] Zellers, In Enemy Hands, 172.

[97] Nellie Dyer Letter to Robert Kisch, July 2, 1953.

[98] Zellers, In Enemy Hands, 172.

[99] Ibid., 175.

[100] Crosbie, Three Winters Cold, 104.

[101] Philip Deane Letter to Walter Kisch, May 5, 1953.

[102] Zellers, In Enemy Hands, 125.

[103] Information about the fates of family members gathered from interview of Eric Kisch by Kevin Ostoyich, September 9, 2017; Walter Kisch Letter to Thoburn T. Brumbaugh; The Central Database of Shoah Victim’s Names (https://yvng.yadvashem.org/index.html?language=en); Joods Monument (https://www.joodsmonument.nl/); and the Holocaust Victims and Survivors Database of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (https://www.ushmm.org/remember/the-holocaust-survivors-and-victims-resource-center/holocaust-survivors-and-victims-database). Note: The databases of the United States Holocaust Museum and Yad Vashem have been given precedence over the details provided in the Walter Kisch letter. (For example, Walter had thought his sister had been killed in Auschwitz and that his brother, Edgar, and sister-in-law, Edith, had been shot in Riga.) The Holocaust Victims and Survivors Database of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum notes that Alfred Kisch was deported from Vienna to Theresienstadt in August 1942 and records the date and place of his death as September 12, 1942 and Theresienstadt, respectively. Walter Kisch claimed in his letter to Thoburn T. Brumbaugh that Walter’s brother Robert, who had been in Theresienstadt, had written that Alfred Kisch had been “transported with the 43. Transport to somewhere but he never arrived of his destination.” In correspondence with the author, Eric Kisch wrote about his cousin, Peter, who had been sent on the Kindertransport by Edgar and Edith: “After a terrible childhood in Scotland (if I recall correctly), Peter went back to Vienna before emigrating to the U.S., where he changed his name to Keyes. Peter died in New York on January 6, 2006. His wife Henny died the following year. Their daughter, Dita […] is married and has one son, Aaron. That is the sum total of what is left of the Kisch side of the family, besides me, [my wife, Susan], and our two kids, [Nina and Jonathan].”

[104] Nellie Dyer Letter to Robert Kisch, July 2, 1953.

[105] Crosbie, Three Winters Cold, 79.

[106] Ibid., 102.

[107] Ibid., 102-103.

[108] Ibid., 103.

[109] Nellie Dyer Letter to Robert Kisch, July 2, 1953.

[110] Deane, Captive in Korea, 39.

[111] Crosbie, Three Winters Cold, 103. For Eltringham’s origins: Zellers, In Enemy Hands, 51.

[112] Crosbie, Three Winters Cold, 103.

[113] Zellers, In Enemy Hands, 20.

[114] Ibid., 154.

[115] Crosbie, Three Winters Cold, 103-104.

[116] Shorty Estabrook, Ex-POW Bulletin, Vol. 67, Nr. 5/6, May/June 2010, 16 (Accessed at https://www.axpow.org/bulletins/may-june10.pdf.)

[117] Eric feels a close affinity and utmost respect for his legendary uncle. For more information on Eric Kisch see Kevin Ostoyich, “Records of Shanghai: One Man’s Quest to Validate Memories of a Family’s Refugee Past,” (/2017/10/records-of-shanghai/).