The White House via Flickr

Who CARES?

Michael Schwan

University of Cologne

Michael Schwan is a DAAD/AICGS Research Fellow from October to December 2021.

Dr. Schwan is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Cologne in Germany where he is part of the Cologne Center for Comparative Politics (CCCP). He studied Political Science, Sociology, Economic,s and Economic Geography in Marburg, Lucerne, and Cologne and holds a PhD from the University of Cologne's Faculty of Management, Economics, and Social Sciences. He spent time in the United States during a research stay at Boston University's Frederick S. Pardee School of Global Studies. As a political economist he is devoted to deciphering socioeconomic foundations and ramifications of financial markets, corporate governance structures, and national growth models. Some of his previous projects have dealt with sovereign debt management, public banking, and regional effects of financial market integration in Europe. Currently, he is working on new forms of institutional ownership, corporate networks, and political-economic reactions to COVID-19.

At AICGS, Dr. Schwan will continue his work on a collaborative project with Prof. Mark Cassell (Kent State) and Prof. Marc Schneiberg (Reed), investigating the role of the U.S. banking system in disbursing economic relief loans as part of the SBA's Paycheck Protection Program. The research analyzes the effects of different lender types, bank ecologies, and political factors on the provision of credit to communities of different demographics. The project addresses important issues on the inclusivity of economic policy-making and local economic development in times of crisis.

The DAAD/AICGS Research Fellowship is supported by the DAAD with funds from the Federal Foreign Office.

Bank Lending, Inclusivity, and the Paycheck Protection Program during COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the U.S. economy in many different ways. A unique combination of business shutdowns, stay-at-home orders, disruptions in global trade, layoffs, and credit defaults presented a demand shock, a supply shock, and a financial shock at the same time. Following a decade of sustained domestic economic expansion, this has caused a drop in Gross Domestic Product relative to the business cycle peak more severe than the Global Financial Crisis, while the world economy witnessed its largest downturn since the Great Depression.[1][2] To counteract some of the detrimental effects of the pandemic on the economy, Congress passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act), a $2.2 trillion spending bill that was signed into law by then-president Trump on March 20, 2020. Representing the largest economic stimulus package in U.S. history, the CARES Act triples in size the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) that followed the Global Financial Crisis and exceeds other more recent important legislation such as the 2021 American Rescue Plan Act ($1.9 trillion) or the INVEST in America Act 2021 (also known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill, $1.2 trillion).

The Paycheck Protection Program

In addition to tax credits, direct payments to U.S. citizens, and investments in health care infrastructure, the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), eventually worth $953 billion, is a key pillar of the CARES Act. Run by the Small Business Administration (SBA), a government agency established in 1953 to support entrepreneurs and small businesses with various lines of credit, the PPP offered low-interest loans from banks and lenders to maintain payroll and cover mortgage payments, lease expenses, and utilities. Every loan is federally guaranteed and if a company meets certain criteria based on full-time equivalent employees and how the loan is spent, it can apply for partial or full forgiveness. As of September 2021, the SBA so far has forgiven 53 percent of all PPP loans, among them nearly all loans (83 percent) made in 2020. Since the number of applications for forgiveness is growing quickly, it can be expected that the eventual loan forgiveness rate will be high with only a few businesses subject to any repayment.[3] Eligibility for a PPP loan hinges on a business having 500 or fewer employees, a tangible net worth not exceeding $15 million, and a net income of no more than $5 million. In total, the SBA has approved more than 11.8 million PPP loans with the average loan being around $68,000.[4] The whole program can be split into three consecutive phases, representing windows during which businesses could apply for a loan: April 3–16, 2020 (phase 1), April 27–August 8, 2020 (phase 2), and January 12–May 31, 2021 (phase 3). Unlike similar programs in other countries like Germany but in line with previous SBA assistance to small businesses, the PPP uses the U.S. system of banks and lenders to distribute the funds. This implies that firms need to approach qualified financial intermediaries which then apply to the SBA and channel the loan. Throughout the course of the program, the SBA has substantially increased the number of certified lenders to cope with the demand for PPP loans and to cover a wider range of borrowers and geographies. During phase 2, for instance, another 600 lenders, both banks and non-depository institutions, were admitted to the program.[5]

Banking, credit provision, and inclusivity

Soon after the CARES Act’s passage, a cottage industry developed around PPP research with the program drawing heightened scrutiny and increased criticism both from media pundits and academics. Scholars have examined which industries and sectors receive PPP loans, the effectiveness of the program, its impact on minority communities, and lending patterns by firm size and location. In addition, some studies and newspaper accounts reference the role banks and lenders play in the program and how the (non-)existence of insider knowledge and bureaucratic capacities was skewed towards larger, more established businesses (see, for instance, Borawski & Schweitzer 2021;[6] Center for Responsible Lending 2020;[7] Chetty et al. 2020;[8] Sanchez-Moyano 2021[9]). However, one of the most fundamental aspects of the program, its reliance on the pre-existing, mainly for-profit system of banks and lenders and the effects thereof, have been largely ignored to date. This is especially noteworthy since the comparative literature on finance and banking has pointed out time and again that banks matter—for better or worse. The distinction between so-called relationship banking on the one hand and market-based banking on the other hand map the discourse. While the former is more in line with traditional intermediation based on spatial proximity between the borrower and the lender, including, very often, long-standing customer relationships built on mutual trust and experience, the latter follows an “originate-to-distribute” strategy in which loans are bundled, securitized, moved off the books, and sold in secondary markets. In this case, lending becomes more impersonal and governed by standardized metrics with fees and commissions income as prime motives.[10] In general, alternative banks like credit unions, public banks, or cooperatives still tend to adhere to relationship banking whereas large derivatives banks like Bank of America, Wells Fargo, or JP Morgan have shifted towards market-based banking. The literature suggests that this matters and further accounts for differences in credit provision to small and medium-sized enterprises as well as inclusivity towards poor and marginalized communities (see, for instance, Berger & Udell, 2006;[11] Baradaran 2015;[12] Schneiberg & Parmentier, 2021[13]). In short, we expect to detect clear differences in PPP lending patterns across different bank types. Furthermore, we expect alternative banks to be more inclusive along lines of class and race.

Analyzing PPP

To substantiate our theoretical claim and test these expectations we provide descriptive and statistical analyses of the full sample of all 11.8 million PPP loans distributed between April 2020 and May 2021. To distinguish bank types we categorized each lender according to the following scheme representing sub-systems of bank types: (1) Top 50 derivatives banks that are large market-based financial institutions; (2) Community banks, which are small, locally-owned and -operating deposit-taking institutions closely tied to local economies; (3) Credit unions representing financial cooperatives owned and operated by depositor-members, engaged in conventional lending practices; (4) Community development financial institutions (CDFI) that are federally certified to assist low-income individuals and communities; (5) institutions of the Farm Credit System (FCS)—a nationwide network of cooperative lending institutions that assist U.S. agricultural firms; and finally (6) financial technology firms, or FinTechs, that harness digital tools for seamless transactions, evident in platforms like https://klikkikasino.io/ where instant payment systems enable efficient operations without physical branches. We also added another battery of variables from the American Community Survey and other databases to control for demographic and socio-economic characteristics as well as differences in local banking markets shaped by these virtual financial ecosystems. We move the unit of analysis from individual loans to more than 32,000 ZIP Code Tabulation Areas (ZCTA) that are statistical entities developed by the U.S. Census Bureau. Other than ZIP codes, which follow historical mail routes and are thus very incoherent, ZCTAs represent distinct geographic units and are a useful tool for fine-grained analysis of socio-economic areas. From this follows a set of summary statistics, descriptive loan and lender characteristics, and statistical models that, inter alia, estimate the effects of high poverty and racial diversity on the number of PPP loans made by different lender types in specific ZCTAs, highlighting how tech-enabled services influenced distribution patterns.

Bank types matter

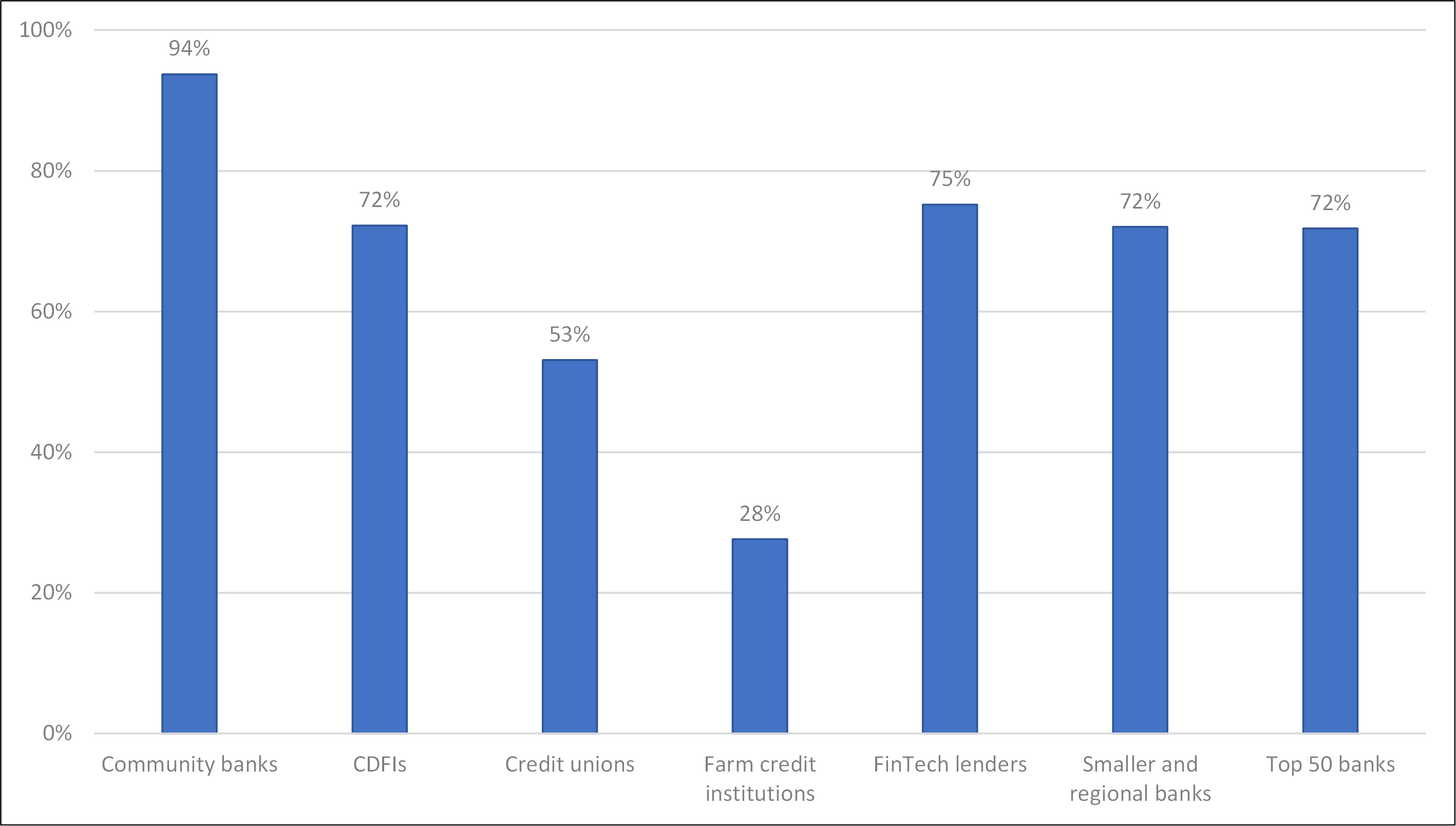

Our results show some clear and expected trends but also reveal other more surprising findings. Figure 1 reports ZCTA coverage rates by lender type as an indicator of where banks do business. A number of remarkable things stand out. First, with a coverage rate of 94 percent, the sub-system of community banks covers most ground and disburses at least one PPP loan in almost every corner of the country. Second, a set of very different lender sub-systems follows suit, with CDFIs, FinTech lenders, smaller and regional banks, as well as top 50 derivatives banks each making loans in roughly three out of four ZCTAs. Trailing behind are, third, the credit unions with a coverage rate of 53 percent with the farm credit system in last place just below the thirty-percent mark. It is no surprise that community banks are on top of the list since they possess the densest lender sub-system in the financial system with several thousand institutions. Also, no surprise is the meager rate of the farm credit system. There are only comparatively few FCS institutions and they are highly specialized in lending to rural areas and agricultural businesses. What stands out, however, is the relatively poor performance of the credit unions as well as the strong showing by the CDFIs. Given that they are much fewer in number, do not have a nationwide network of branches (unlike the top 50), and rely on a physical presence in a neighborhood (unlike the FinTechs), their strong performance is remarkable.

Figure 1 Where lenders do businesses: ZCTA coverage rates.

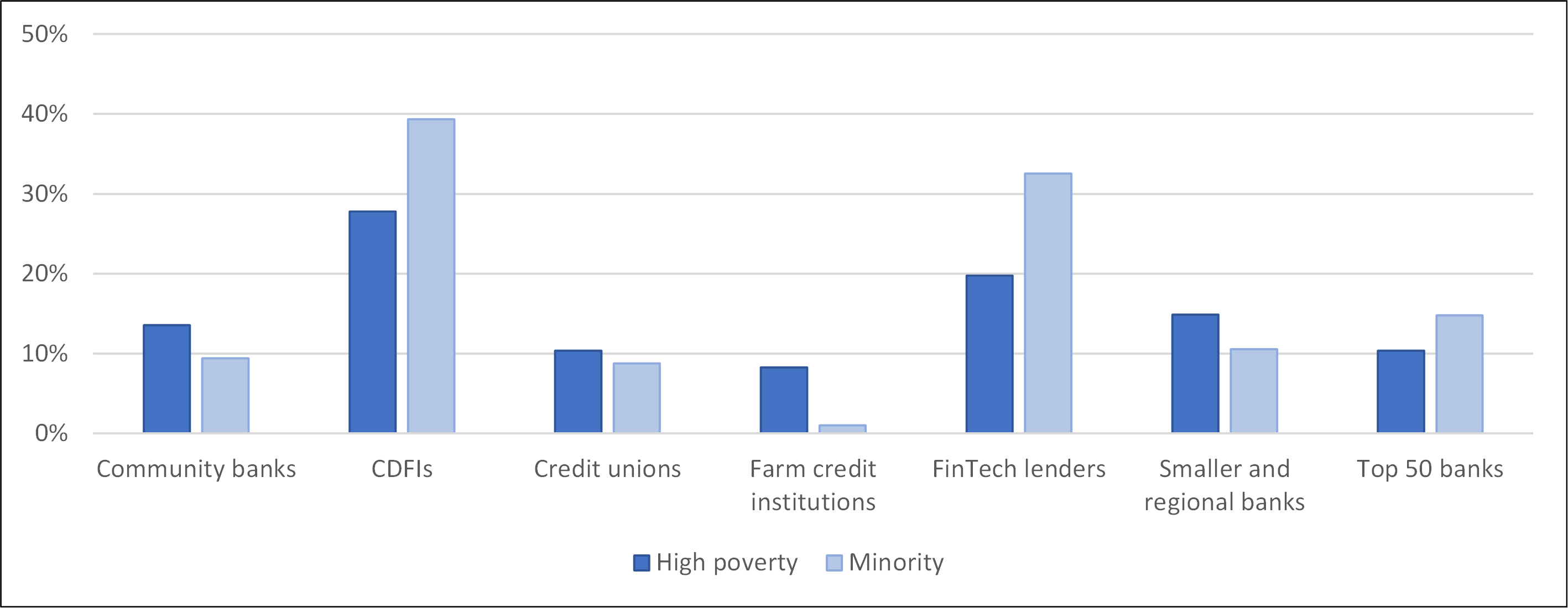

Zooming in on communities with high poverty rates and more diverse demographics, figure 2 illustrates specific lending profiles by bank type. Here it becomes clear that both CDFIs and FinTech lenders by far focus most on those areas. Close to 30 percent of all PPP loans disbursed by CDFIs and nearly 20 percent of those made by FinTechs went to a high poverty ZCTA, whereas all other lender types hover around the ten-percent mark. Overall, poor communities were underserved during the course of the program, which makes the contributions by CDFIs and FinTechs even more valuable. Although lending exclusivity is more pronounced in terms of class than race, the contrast between bank types becomes even starker when looking at minority-majority communities. Here, nearly 40 percent of all CDFI loans and almost one in three FinTech loans went to such areas, followed by top 50 banks. These results are backed by our statistical analysis using different ZINB modeling techniques and various robustness checks.

Figure 2 Lending specificity in poor and minority areas by bank type.

Outlook and policy implications

While community development financial institutions seem to have lived up to the task, the underperforming results by other alternative banks—community banks, credit unions, and farm credit institutions—present a puzzle. Moreover, top 50 derivatives banks are inclusive along racial lines, and FinTech lenders exhibit a large degree of inclusivity. As this deserves further attention and scrutiny, we would like to highlight three major implications for future research and policy debates:

- Bank types clearly matter. Relying on a pre-existing system of different institutions for the distribution of public loans might make use of distinct specializations, such as the connection between farm credit lenders and agricultural firms. Yet, it also can exacerbate existing divisions that reinforce the underserving of communities of color and high poverty. While specific mechanisms leading to lending decisions are yet to be fully understood—including loans to different businesses and of different sizes—a more focused program design could alleviate some of the shortcomings and prevent them from happening in the future. One of the adjustments in phase 3, starting with the Biden administration, for example, led to a dedicated amount of PPP money to be distributed exclusively via CDFIs.

- Due diligence, monitoring, and oversight might have to be improved. During the first phase, mainly top 50 banks handed out large loans, very often to bigger firms. Since applicants only had to certify in good faith that they needed a loan and banks cashed in on set fees with no risk of default, fraudulent practices occurred. During the third phase, this shifted to self-employed and independent contractors that were largely served by FinTech lenders. This takes away some of their inclusivity benefits and poses new questions of how to effectively regulate their loan generating business model.

- Eventually, a look across the Atlantic might encourage further policy learning. Streamlining the program with a clear focus on liquidity provision for mortgage and utility payments, while setting up an employment retention scheme similar to the German Kurzarbeit could increase the effectiveness of PPP lending and simultaneously de-incentivize fraudulent applications. Ideally, this would go hand in hand with the establishment of a set of public development banks such as the German Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW). Currently, North Dakota is the only U.S. state with such an institution, while others, including New Jersey under Governor Murphy, have developed concrete plans. This could help foster private-public bank relationships as well as direct relations between private businesses or even households and a public lender, which, in the end, would foster mutual trust, economic security, risk sharing, and monitoring capacities.

This report presents initial findings of a larger transatlantic research project on the political economy of financial assistance during COVID-19 in the United States and Germany, jointly conducted with Mark Cassell (Kent State University) and Marc Schneiberg (Reed College). Further results are accepted for presentation at the Boston Fed in spring 2022.

References

[1] Bauer, L., Broady, K., Edelberg, W. and O’Donnell, J. (2020). Ten facts about COVID-19 and the U.S. economy. The Hamilton Project. Brookings Institution, September 17, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/research/ten-facts-about-covid-19-and-the-u-s-economy/

[2] Gopinath, Gita (2020). The Great Lockdown: Worst Economic Downturn Since the Great Depression. IMFBlog, April, 14, 2020. https://blogs.imf.org/2020/04/14/the-great-lockdown-worst-economic-downturn-since-the-great-depression/

[3] Medici, Andy (2021). SBA has forgiven more than half of all PPP loans. The Business Journals, September 13, 2021. https://www.bizjournals.com/bizjournals/news/2021/09/10/sba-has-forgiven-more-than-half-of-all-ppp-loans.html

[4] Small Business Administration (SBA) (2021). Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) Report. Approvals through 05/31/2021. https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/2021-06/PPP_Report_Public_210531-508.pdf

[5] Government Accountability Office (GAO) (2021). Paycheck Protection Program. Program Changes Increased Lending to the Smallest Businesses in Underserved Locations. GAO-21-601, September 2021. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-21-601.pdf

[6] Borawski, G., & Schweitzer, M. E. (2021). Which Industries Received PPP Loans? Economic Commentary, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.26509/frbc-ec-202108

[7] Center for Responsible Lending. (2020). The Paycheck Protection Program Continues to be Disadvantageous to Smaller Businesses, Especially Businesses Owned by People of Color and the Self-Employed. https://www.responsiblelending.org/sites/default/files/nodes/files/research-publication/crl-cares-act2-smallbusiness-apr2020.pdf?mod=article_inline

[8] Chetty, R., Friedman, J., Hendren, N., Stepner, M., & Team, T. O. I. (2020). The Economic Impacts of COVID-19: Evidence from a New Public Database Built Using Private Sector Data Working Paper No. 27431. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w27431

[9] Sanchez-Moyano, R. (2021). Paycheck Protection Program Lending in the Twelfth Federal Reserve District. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Community Development Research Brief Series. https://doi.org/10.24148/cdrb2021-01

[10] Hardie, I., Howarth, D., Maxfield, S. & Verdun, A. (2013). Banks and the False Dichotomy in the Comparative Political Economy of Finance. World Politics, 65(4), 691-728.

[11] Berger, A. N., & Udell, G. F. (2002). Small Business Credit Availability and Relationship Lending: The Importance of Bank Organisational Structure. The Economic Journal, 112(477), F32–F53. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00682

[12] Baradaran, M. (2015). How the other half banks: Exclusion, exploitation, and the threat to democracy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

[13] Schneiberg, M., & Parmentier, E. (2021). Banking structure, economic resilience and unemployment trajectories in US counties during the great recession. Socio-Economic Review. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwaa039

Supported by the DAAD with funds from the Federal Foreign Office (FF).