Daniel Huizinga via Flickr

Trust and Distrust in Civic Institutions

Frank Reichert

University of Hong Kong

Prof. Frank Reichert is a DAAD/AGI Research Fellow in Fall 2024.

Frank Reichert is a professor at the University of Hong Kong and affiliated with the Center for Inclusive Citizenship at the Leibniz University of Hannover in Germany. He has previously worked at universities and research institutions in Germany and Australia and held several prestigious fellowships, including a Spencer Postdoctoral Fellowship from the U.S. National Academy of Education. He currently co-chairs the Standing Group on Citizenship of the European Consortium for Political Research. As an international expert, he also contributes to the International Civic and Citizenship Education Study (ICCS) 2027 of the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA).

Prof. Reichert has published widely on civic education and citizenship norms, digital citizenship, and youth civic development. His research often examines multilevel data through advanced statistical techniques or mixed-methods approaches. Some of his contributions include harnessing underexplored large-scale data and pioneering person-centered statistical techniques in the field of civics and citizenship. He also co-developed a comprehensive digital competence assessment instrument and was commissioned by UNESCO to prepare a background report for the 2023 Global Education Monitoring Report. Furthermore, he has received various competitive awards for research excellence and knowledge exchange.

At AGI, he will expand his work on youth civic development through the comparative analysis of representative large-scale data from adolescents and adults in Germany and the United States. This research aims to further our understanding of the current state of democracy in both countries by illuminating the precursors of populist sentiment and anti-democratic attitudes in adolescence. This work can help contribute insights for generating solutions to the multiple crises of democracies and anticipating future challenges to democracy.

Generational Differences in Germany and the United States

Trust in civic institutions, such as government, courts, or the media, is essential for the effective functioning of a political system and particularly critical for democratic societies where citizens collectively choose their political leadership in free elections. However, it appears that such trust is not particularly high in several Western democratic societies. The recent Edelman Trust Barometer suggests that developing countries, including authoritarian and non-democratically constituted societies, top the list, whereas established democracies rank relatively low in civic trust. For example, the United States and Germany were very similar in ranking, scoring only 46 and 45 out of 100 in 2024, down from 48 and 46 in 2023, respectively. These data indicate that the populations of both countries have relatively little trust and that they are becoming less trusting in civic institutions.

However, many social scientists and political stakeholders argue that low levels of trust in civic institutions can be problematic, as trust serves several functions (see UNDESA, 2021, and UNDP, 2021). When people trust institutions, they are more likely to comply with laws and regulations and to use and support public services provided by these institutions, making it easier to implement policies and achieve desired outcomes. Trust in public institutions also allows for more policy options, and it grants longer timeframes for policies to yield results. This view is backed by survey data showing that nearly two-thirds of Americans believe low trust in government makes it harder to solve the country’s problems. Trust in civic institutions also fosters social cohesion and stability, ensures peaceful transitions of power, and reduces the likelihood of political unrest. Furthermore, political trust reduces the likelihood of voting for populist candidates and protest parties.[1]

However, having very high trust in civic institutions can also be dangerous. When people have very high civic trust, they may accept information and decisions from authorities without critically evaluating their validity or fairness and fail to hold institutions accountable or even notice when corruption or mismanagement flourish. In addition, when people have very high trust in civic institutions, they may overly rely on them to solve problems instead of getting involved, which could diminish the quality and vibrancy of democracy.

Accordingly, it seems important for the stability of a democratic society that its citizens have reasonable levels of trust and critically evaluate the institutions’ performance. Declining levels of civic trust can pose challenges to democratic societies, raising the question of why trust in civic institutions is changing. Some explanations involve generational changes. While cultural theories suggest that trust in institutions is an extension of interpersonal trust that people develop early in life, institutional theories argue that individual experiences with and evaluations of civic institutions influence trust in them.[2] Whereas the former perspective implies that civic trust does not change much in adulthood, the latter suggests that trust can change at any age influenced by direct experiences people have with civic institutions. It has also been argued that values such as tolerance and social justice are becoming more important in Western societies and that this development is driven by younger generations (who also happen to be better educated) due to differences in the societal conditions they are experiencing (e.g., Dalton, 2020;[3] Inglehart, 1997[4]). As a result, younger generations may be more critical of civic institutions, potentially explaining observed declines in civic trust.[5]

Adults in Germany and the United States can be categorized by their trust in civic institutions

In my research, I look at generational differences in adults’ civic trust. In contrast to most other studies or reports, I neither focus on just one institution at a time nor merge different institutions into an overall trust score. Instead, I aim to develop a typology of trust in civic institutions that can help differentiate between individuals based on their “trust profiles” (e.g. some people may have low trust in all kinds of civic institutions while others may trust only some institutions). Identifying similarities and differences in generational patterns along such a trust typology can offer nuanced and practically useful insights. Here, I focus on adults’ confidence in eight civic institutions, primarily drawing on my analyses of the most recent data from the World Values Survey (WVS) that were collected in three waves between 2006 and 2018 in Germany and the United States (among other countries).

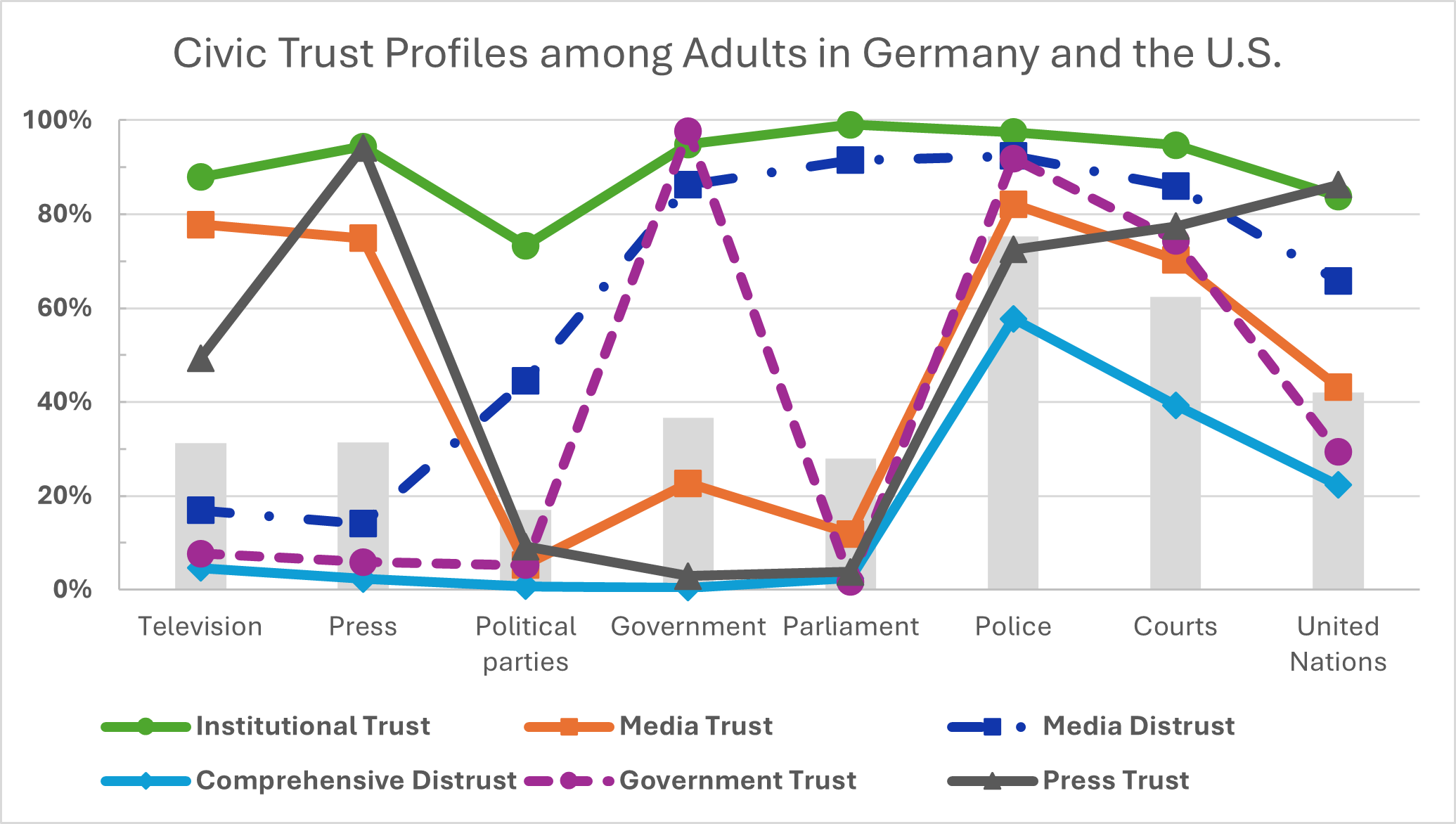

Before turning to the trust typology, the cumulated WVS data from Germany and the United States (the grey bars in Figure 1) offer initial insights. For example, confidence in (traditional) media and political institutions is relatively low (and lowest for political parties), while confidence in justice-related institutions, especially courts and the police, is much higher. Notably, adults in Germany tend to report higher levels of confidence in almost all eight institutions than adults in the United States. In Germany, confidence in most institutions was lowest in 2006, and it consistently increased from 2006 until 2018 for the three justice-oriented organizations (i.e., courts, the police, and the United Nations [UN]). In contrast, U.S. adults’ confidence was higher in 2006 than in later years for half of these institutions; exceptions are the UN and the press (highest levels of confidence in 2017) as well as courts and the police (relatively stable levels of confidence). In other words, there are somewhat different trends in the patterns of trust in these two countries.

Figure 1

Note. Grey bars show the overall percentages of adults with relatively much confidence in civic institutions (i.e., “a great deal” or “quite a lot”). Each colored line represents a distinct trust profile, with markers reflecting the proportions of adults characterized by the respective profile with relatively much confidence in these institutions. (Differences to 100% comprise adults with relatively low—i.e., “not very much” or “none at all”—confidence.) Source: My analysis of WVS data from Germany (2006, 2013, and 2018) and the United States (2006, 2011, and 2017), Waves 5-7.[6]

This is the source of my conclusions, and using a statistical method called latent class analysis (e.g. Collins & Lanza, 2010[7]) helps to build a trust typology by revealing six trust profiles among adults. One group of adults reports relatively much confidence in all eight institutions (“Institutional Trust”). A second profile characterizes adults with relatively much confidence in (traditional) media, as well as in courts and the police, while at the same time displaying relatively low confidence in political institutions. This profile can be called “Media Trust.” Quite the contrast is a profile that can be called “Media Distrust,” as it reflects relatively little confidence in traditional media and fairly much confidence in all other institutions, except for political parties that generally receive little confidence. A fourth profile is characteristic of adults who tend to report relatively little confidence in all eight institutions, perhaps with the exception of the police (“Comprehensive Distrust”). In my analysis of data from adolescents 25 years ago (sourced from the Humboldt University of Berlin & University of Maryland-College Park, 2016[8]), I also identified these four profiles, lending support to their robustness over time and across ages.

The remaining two trust profiles in Figure 1 are only observed among adults. On the one hand, one profile displays high confidence in government, in addition to relatively high confidence in courts and the police (“Government Trust”). On the other hand, the last profile characterizes adults with relatively much confidence in the press and in justice-related institutions (“Press Trust”).

Adults in Germany and the United States differ in their institutional trust profiles

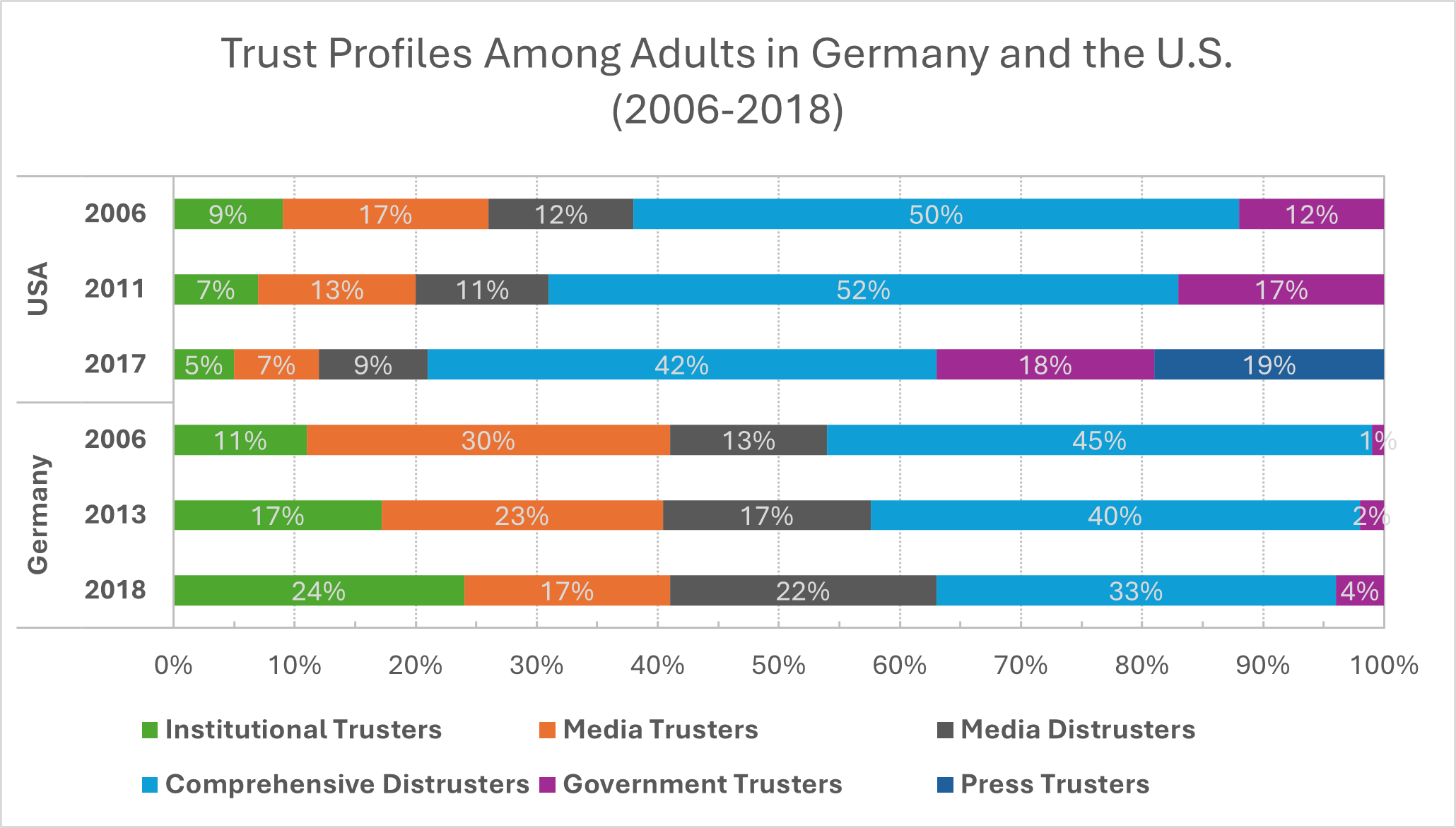

Although adults in Germany and the United States can be characterized by specific profiles of their trust in civic institutions, marked differences between both countries and across time, shown in Figure 2, must be acknowledged. Institutional Trusters and Media Distrusters—both sharing relatively much confidence in political institutions—were about equally common among adults in both countries in 2006. However, their proportions subsequently changed in opposite directions and became more common among adults in Germany and less common among those in the United States. In contrast, Media Trusters became less common in both countries, though larger proportions of these adults are found in Germany compared to the United States. Despite a decline in prevalence, Comprehensive Distrusters represented the largest group of adults in both countries in all three waves.

Now for a comparison of the adolescent Millennials of 25 years ago with adults (including Millennials) surveyed more recently. The two trust profiles that appear among adults (but not among adolescents 25 years ago) are (almost) absent in Germany, yet sizable in the United States. While Government Trusters to whom the government is the only trustworthy political institution became more common, Press Trusters only appeared in 2017 (which is also the first year when Generation Z was surveyed).

Figure 2

Source: My analysis of WVS data (Waves 5-7) from Germany in 2006, 2013, and 2018, and from the United States in 2006, 2011, and 2017.[9]

In fact, the Press Trust profile emerged from the Media Trust profile early during the first Trump administration; it is driven in the United States by declining confidence in TV and—perhaps somewhat surprising—increasing confidence in the UN. While Media Trusters have relatively much confidence in both TV and the press, they cannot be differentiated from other adults with respect to their confidence in the UN. Conversely, Press Trusters report relatively much confidence in the press and in the UN, but they cannot be differentiated from other individuals based on their confidence in TV.

Generational differences in adults’ institutional trust profiles

In Germany, the generational relationship for Institutional Trust is u-shaped while that for Comprehensive Distrust reflects an inverse u-shaped pattern: Baby Boomers and members of Generation X are less likely Institutional Trusters and more likely Comprehensive Distrusters than other generations. The oldest generations surveyed in the WVS (i.e., Silent and Greatest Generations) are more often Institutional Trusters and less frequently Comprehensive Distrusters than other generations. The proportions of younger generations (i.e., Millennials [Generation Y] and Generation Z) in these two trust profiles are somewhere between those of the other generations. In addition, although there were no generational differences in the proportions of Media Trusters almost 20 years ago, they have become increasingly uncommon in younger generations since then and represent the smallest group among Generation Z (in 2018). Finally, there were no notable generational differences for Media Distrust and Government Trust in Germany.

As in Germany, Comprehensive Trust is least common among Baby Boomers and Generation X and relatively common among younger and older generations in the United States. However, younger generations over-proportionately are Comprehensive Distrusters in 2017; a similar though weak trend is also visible for 2006—both years during Republican governments. However, in 2011—during the first Obama administration—generational differences were relatively small; at that time, Baby Boomers and Generation X were even slightly more frequently Comprehensive Distrusters than other generations.

Differences in the remaining trust profiles are small and hardly significant across generations in the United States. The trends tentatively suggest an overall pattern for Media Trust similar to that in Germany (i.e., slightly less common in younger generations). This pattern is even clearer for the Government Trust profile, especially in 2017, and similar but very weak for Press Trust (which only emerged in 2017). In contrast, Media Distrusters are slightly more common among younger generations, though this pattern is clearest for 2011, lending additional support for their greater trust in political institutions during the first Obama administration.

Conclusions and recommendations

Despite the ongoing nature of this research, there is clear evidence for a typology of trust in civic institutions. Adults in Germany and in the United States can be categorized into Institutional Trusters, Media Trusters, Media Distrusters, and Comprehensive Distrusters (four profiles also observed among adolescent Millennials in both countries 25 years ago), as well as Government Trusters and Press Trusters who are quite common among adults in the United States but relatively rare in Germany (and were not observed among adolescent Millennials). Institutional trust also seems to drop during late adolescence or early adulthood, and the broader set of trust profiles among adults, especially in the United States, indicates that personal experiences with and knowledge of civic institutions as well as external events (e.g. 9/11, the global financial crisis, or the COVID-19 pandemic) may be very relevant in shaping citizens’ trust in civic institutions.

Sizable proportions of adolescents who display little trust in civic institutions must be viewed as a clear warning sign.

Differences in the media and political systems also appear to contribute to differences in adults’ civic trust. Declining trust in TV appears to drive Media Distrust (especially among younger generations and during more value-liberal governments) and Press Trust (mainly among older generations). It seems possible that the changes in trust seen in 2017 in the United States can be linked to Trump’s first presidency and his highly populist election campaign. I speculate that the changing media landscapes and the more politicized media—especially TV and more specifically Fox News in the United States—are among the drivers of these developments. The deregulation of the American media markets during the 1990s might (inadvertently) have contributed to less trust in media that seem to consider meeting certain professional and ethical standards less important than the quality and accuracy of reporting.

To support this point, analysis of more recent data from the American National Election Study suggests that older generations continue to have more confidence in traditional media (i.e., TV networks and the press) than in social media compared to younger generations. Only the Silent Generation (the oldest generation in this analysis) reports more confidence in Fox News than in the New York Times. In contrast, younger generations have more confidence in social media networks such as Facebook, though it is nevertheless much lower than confidence in traditional media. Research on 14-year-old adolescents in North-Rhine Westphalia, Germany, suggests that trust in social media may be even lower than that in political parties.[10] Hence, the introduced typology of civic trust may need to be amended in the future.

There is also some tentative evidence that the identified generational differences in the explored trust profiles may, in part, result from a value change among younger generations. For example, younger and older generations more likely are characterized by Institutional Trust than Baby Boomers and Generation X. Younger generations also tend to be less commonly Media Trusters, Government Trusters, and Press Trusters, which may be indicative of a broader pattern among young people who have been found to be less trusting of traditional media than older generations. Interestingly, Comprehensive Distrust appears linked to who is in government, at least in the United States where the youngest generations had the highest proportions of Comprehensive Distrusters during Republican governments (especially during the first Trump administration), which tend to be driven by more conservative and less social justice-inspired values than Democrat governments. Future data collections might allow examining this association also for Germany, where changes in government between 2006 and 2018, when Angela Merkel was the German chancellor, were less drastic than in the United States.

As people appear to become more distrustful during late adolescence or/and early adulthood, seeing sizable proportions of adolescents who display little trust in civic institutions must be viewed as a clear warning sign. Therefore, educational policies and practices should address potential issues of distrust among young people more consistently in ways that ensure all young people can experience civic institutions and discourse and learn to understand the political process while in school. These efforts should not end with formal schooling but need to be continued into adulthood, when significant changes happen in people’s lives as they leave their homes, enter the job market, and start families.

Furthermore, instead of the common focus on disagreement, bipartisan efforts should be encouraged where opponents treat each other respectfully and where governments help everyone comprehend their policies and institutional processes in a language that people understand. Sensationalist, dramatizing, and polarizing political debates, issue proposals, and media reporting (including on social media) must be avoided. The personalization of U.S. politics as well as the politicization of the media and of other civic institutions (including the Supreme Court) seem problematic and may be one reason for the dramatic changes in (political) trust in the United States compared to Germany. More—or better—media regulation may be one solution; this may even be in the very interest of media platforms that might benefit from greater trust in their programming. Questions policymakers should ask include whether there is a need for a new code of ethics for journalists and media platforms; what consequences the reporting and forwarding of dis-, mis- and biased information must have to reduce their spread; and whether TV channels should be required (again) to air a certain number of hours of balanced programming.

Finally, the recent election results, both in Germany (state level) and the United States (federal level), as well as the prevalence of social media among younger generations who seem less trusting in some regards, demand looking at recent data on civic trust to test the robustness of the developed typology following the COVID-19 pandemic. Regional and demographic differences also need to be considered to understand better the individuals characterized by the different trust profiles. For example, initial analyses suggest that Institutional Trusters and Media Trusters are more common in west Germany while Comprehensive Distrusters more frequently reside in east Germany. There is also indicative evidence suggesting that Press Trusters less commonly live in the southern United States or that people not affiliated with a religion are less likely Comprehensive Distrusters. Exploring these links further can contribute to tailoring public policies in ways that ensure all citizens can develop some trust in civic institutions while also approaching them through a critical lens. Future research should also consider methods such as those applied here to explore what occurs in the mid-twenty-first century. It would be especially helpful if the United States resumed participation in the International Civic and Citizenship Education Study (and if Germany did this nationwide instead of only with one or two states) to monitor trends in civic trust and citizenship among adolescents who will become adult voters in the future.

Acknowledgments: I would particularly like to thank Thomas Protzman for supporting the analysis of the ANES data, Nandita Suri for assisting me with the literature review, and Judith Torney-Purta for critically reviewing an earlier draft of this essay.

[1] M. Hooghe, “Trust and elections,” in The Oxford Handbook of Social and Political Trust, ed. E. M. Uslaner (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), pp. 617-632.

[2] I. Schoon & H. Cheng, “Determinants of political trust: A lifetime learning model,” Developmental Psychology 47, no. 3 (2011), pp. 619-631.

[3] R. J. Dalton, The Good Citizen: How a Younger Generation Is Reshaping American Politics (3rd ed.) (Sage, 2020).

[4] R. Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997).

[5] R. J. Dalton, “Political trust in North America,” in Handbook on Political Trust, ed. S. Zmerli & T. W. G. van der Meer (Cheltenham: Elgar, 2017), pp. 375-394.

[6] C. Haerpfer, R. Inglehart, A. Moreno, C. Welzel, K. Kizilova, J. Diez-Medrano, M. Lagos, P. Norris, E. Ponarin, & B. Puranen et al. (eds.), World Values Survey Trend File (1981-2022) Cross-National Data-Set, JD Systems Institute & WVSA Secretariat, Data File Version 4.0.0, 2022.

[7] L. M. Collins & S. T. Lanza, Latent Class and Latent Transition Analysis: With Applications in the Social, Behavioral, and Health Sciences (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2010).

[8] Humboldt University of Berlin, & University of Maryland-College Park, IEA Civic Education Study, 1999: Civic Knowledge and Engagement Among 14-Year-Olds in 23 European Countries, 2 Latin American Countries, Hong Kong, Australia, and the United States, ICPSR, data version 3, November 7, 2016.

[9] C. Haerpfer, R. Inglehart, A. Moreno, C. Welzel, K. Kizilova, J. Diez-Medrano, M. Lagos, P. Norris, E. Ponarin, & B. Puranen et al. (eds.), World Values Survey Trend File (1981-2022) Cross-National Data-Set, JD Systems Institute & WVSA Secretariat, Data File Version 4.0.0, 2022.

[10] J. F. Ziemes, K. Hahn-Laudenberg, & I. Birindiba Batista, “Politische Unterstützung: Vertrauen, Responsivität und Akzeptanz staatlicher Maßnahmen,” in ICCS 2022: Schulische Sozialisation und politische Bildung von 14-Jährigen im internationalen Vergleich, ed. H. J. Abs, K. Hahn-Laudenberg, D. Deimel, J. F. Ziemes (Münster: Waxmann, 2024), pp. 133-151.

Supported by the DAAD with funds from the Federal Foreign Office (FF).