No Place to Stay? Discrimination Patterns in the German and American Rental Housing Markets

Thomas Hinz

University of Konstanz

Prof. Dr. Thomas Hinz was a DAAD/AICGS Research Fellow in 2016. His research at AICGS focuses on the contexts of ethnic discrimination in rental housing markets. Based on rich empirical data from field experiments, he investigates different forms of discrimination against migrants with a Turkish background when they apply for rental housing in Germany. His stay in Washington, DC, aims to include the broad range of empirical studies on discrimination in the U.S. housing market in his research, particularly on the question of how discrimination and residential segregation are intertwined.

Thomas Hinz is a professor of sociology and empirical social research at the University of Konstanz, Germany. He earned his PhD degree in sociology at the Ludwig Maximilians Universitaet (LMU) Munich and was a visiting scholar to CIQLE at Yale University in 2008. From 2010-2015, he served as Dean of the Humanities of the University of Konstanz.

Things have changed. While for a long time German politicians have tried to define Germany as a ‘non-immigration country,‘ it is now one of the countries receiving the most migration movements in the western world. Of course, this can be largely attributed to a very specific situation, with over 800,000 refugees arriving in the country during 2014 and 2015. However, the numbers of migrants were increasing even before this happened. Even if it is presently unclear just how many refugees and migrants will stay in Germany permanently, challenging tasks lie ahead. Politicians from all democratic parties as well as government officials at the national and local level recognize that immigration affects many areas of society and that policy responses are required with regard to labor markets, education, culture, security, and housing. All these fields intersect to a certain degree and all involve both short- and long-term perspectives. Most crucially, migrants need skills to be successful in the labor market, with language acquisition being a basic requirement. While the process of integration into the educational system and the labor market as well as cultural assimilation will take years, it remains an open question where and how new migrants will live in Germany. The great majority of refugees are currently residing in specific locations – buildings formerly used as hotels or offices or vacant apartment buildings. In Berlin, even a former airport is serving as a temporary residence. All these housing arrangements are obviously only short-term solutions. One of the key challenges will be how migrants find their way into the regular housing market and, more precisely, into rental housing. This is particularly important given that this mode is dominant over property ownership in Germany, particularly for low-income households. How well is Germany prepared for this challenge, which seems even more demanding for a society that has, for so long, considered itself a ‘non-immigration society?’

Whenever migrant-related housing and integration issues are raised, particularly in countries such as the United States with a more pronounced immigration tradition than Germany, the question of housing segregation and discrimination comes into the picture. Housing segregation means that people sort (and are sorted) into neighborhoods by shared characteristics such as language, ethnic origin, or race, etc., which are often correlated with socio-economic status. In the rental housing market, discrimination is defined as ‘unequal treatment’ by the people that make decisions about whom to rent a flat to (such ‘gatekeepers’ are landlords, housing agents, housing companies, etc.) on grounds that are not related to the object of a rental contract. For instance, they may prefer renters of a specific ethnic group ceteris paribus, i.e., all relevant information about renters’ economic resources and creditworthiness being equal. Usually, research on discrimination differentiates between taste-based discrimination and statistical discrimination. The former is based only on the preferences of the individual decision-maker and can lead to a situation wherein the decision-maker has to ‘pay’ to have his preferences realized. Statistical discrimination, on the other hand, results from an information problem. Because decision-makers do not have full information about the creditworthiness and future behavior of a potential renter, they use proxies as a signal for this information, such as easily accessible information about being a member of a certain ethnic group. Statistical discrimination reflects choices made based on differences in average relevant characteristics (e.g., socioeconomic status, income) across the groups. This kind of discrimination is rational, whereas taste-based discrimination is rooted in prejudice.

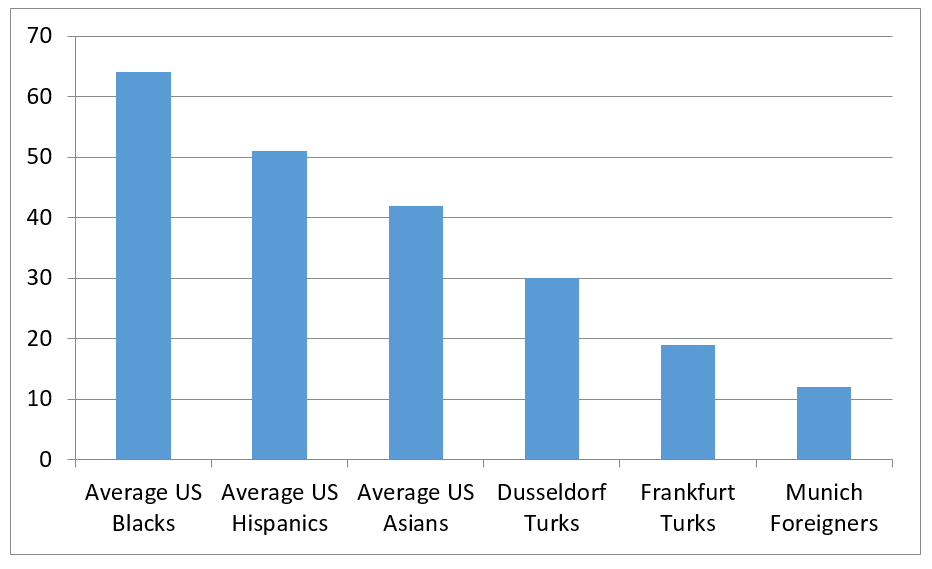

The German legal framework to fight both kinds of discrimination (allgemeines Gleichbehandlungsgesetz) was implemented in 2004 due to European Union initiatives. The U.S. equivalent would be the Fair Housing Act, which is part of the Civil Rights Act. In Germany, the rental housing market is mentioned in this law in light of an extra clause, restricting the area of application to cases of housing companies with at least fifty rental units on the market. In other words, most private landlords are exempt from the general ban on discriminatory behavior. In countries with stricter anti-discrimination legislation such as the United States, residential areas are often more segregated than in countries with a weaker anti-discrimination tradition. In an already highly segregated environment, decision-makers can avoid direct discrimination because residents sort into segmented areas without them applying any discriminatory practices.[1] With a very few exceptions, German urban regions are today far less segregated than most cities in the United States, and this can be seen as an opportunity for the integration process (for illustration see Figure 1).[2]

Figure 1: Segregation indices for selected groups and cities

Source: Iceland, J. (2014): Residential Segregation. A Transatlantic Analysis. Washington DC: Migration Policy Institute.

Although it had been only rarely acknowledged by politicians until the most recent waves of refugees arrived, Germany has had some experience with migrants and their integration over the last decades. Compared to other migrant-receiving countries, the integration of migrant minorities has been more successful than is often assumed by the German public.[3] However, when considering, for instance, Turkish migrants (who form the largest migrant group in Germany), there is broad evidence that indicates they are still disadvantaged in the housing market.[4] Migrants in general live in flats with few amenities, live more commonly in poorer neighborhoods, and often have temporary housing contracts or subletting arrangements.[5] However, it is still questionable whether these disadvantages are caused by ‘unequal treatment’ specifically in relation to housing or actually simply reflect their disadvantaged socio-economic status. This question and the need to better understand what drives potential discrimination in the rental housing market were the starting points of a large-scale research project conducted in six urban regions in Germany (Berlin, Hamburg, Hanover, Duisburg, Leipzig, and Munich).[6] The research team from the University of Konstanz conducted over 2,000 field experiments to detect discrimination defined as unequal treatment. This was done using so-called correspondence tests. Researchers sent out pairs of applications to advertised rental apartments by e-mail. The experimental stimulus was given by the names of applicants, which were either Turkish or German sounding, but for male applicants only. Some of the e-mails contained additional information signaling economic resources in order to test the prevalence of statistical discrimination. This was done by mentioning either a high status (e.g., computer scientist) or a low status occupation (e.g., construction worker) in the applications. One particularly noteworthy feature of the project was that the specific neighborhoods of the rental units under study could be identified.

Such field experiments typically measure ‘discrimination’ by a straightforward method: the difference in response rates between both groups (‘Turkish names’ vs. ‘German names’). If the applicants from the experimental group (‘Turkish names’) receive fewer responses than the control group (‘German names’), they are deemed to be disadvantaged regarding market access. It is obvious that this method focuses only on the first steps of the search process. Despite further methodological questions, this approach has often been used to detect ‘unequal treatment.’[7]

The results of the project confirm that there is discrimination in the rental housing market in Germany, just as there is in many other countries. Interestingly, the discrimination rates[8] measured are lower than the subjective feelings of being discriminated against suggest they would be. In survey studies, respondents with a Turkish migration background assumed that they were discriminated against when searching for housing in a range from twenty to forty percent.[9] The field experiments yielded rates between 10 to 15 percent, which, although lower, is still significant. Surprisingly, the rates turned out to be relatively stable across different urban market conditions. In particular, in those markets with huge demand for rental housing (i.e., in urban regions such as Berlin, Hamburg, and Munich), we would expect discrimination rates to be higher because decision-makers rarely have to ‘pay’ for satisfying their discriminatory preferences. More fine-grained analyses with additional data from rural regions, however, point to lower discrimination rates in regions with a shrinking population.

In terms of the two kinds of discrimination, the results provided evidence for both of them. Discrimination rates were lowered approximately by about one half when applicants provided additional information about their occupation. This information might be considered to be too sparse for decision-makers to draw conclusions about potential renters’ economic resources but nevertheless this additional piece of information proved very effective in terms of the experiment. Interestingly, the decrease in discrimination rates appeared almost exclusively for applicants with high-status occupations. For applicants with low-status occupations, the gap in responses hardly changed. Moreover, taste-based discrimination did not vanish when the discrimination rates were lowered in total by fifty percent.

What about the interdependence of residential segregation and discrimination? Previous research from the United States provided credible evidence for steering processes. The ‘gatekeepers’ of the housing market prefer applicants who match the majority population of the neighborhood to applicants from minority groups. In Germany, the pattern is different and the results rather puzzling. When comparing high-level regional aggregates (i.e., Landkreise – the U.S. equivalent would be counties), discrimination is more pronounced in units with a low proportion of migrants already living there. Yet the more fine-grained the unit of analysis becomes (i.e., at the neighborhood level) the less clear the picture. In contrast to the expectation, the pattern of discrimination against Turkish applicants was highest in urban neighborhoods that already had a high proportion of residents with a Turkish migration background. Note again that the degree of residential segregation is comparably low in German cities. In addition, some neighborhoods with a higher proportion of residents of Turkish descent are beginning to experience the gentrification process, i.e., potential renters with expectedly higher economic resources might be preferred as new tenants.

A further finding refers to discrimination by price. When holding housing quality constant, applicants with Turkish names experienced less discrimination when seeking apartments from a high price market segment. Vice versa, they were more disadvantaged when the apartments are low priced – given the location and quality. This could explain why members of the Turkish minority in Germany end up in worse but more expensive rental housing.

What can be learned from this research in regard to the challenges ahead? It can be expected that new migrants to Germany will have distinct difficulties finding a place to live because of both taste-based and statistical discrimination. When the first step of access to the rental housing market is the point of focus, it seems to be relevant to provide more information about the applicants’ employment perspectives. More information seems to reduce the discrimination rates. Most certainly, however, this will not be enough on its own. Given the high number of migrants and refugees arriving recently, housing policy will become a major issue. The rental housing market with private landlords and profit-oriented housing companies will not succeed in providing enough affordable places to live.

As in the post-World War II period, the federal state, the states, and communities will have to once again support programs for social housing projects. This implies a significant policy shift in German politics since the federal government has cut its support to social housing programs almost completely. Although there are considerable numbers of vacancies in some regions, this will not help because they are mostly in those regions where the new migrants are least welcome and where the labor market offers few opportunities. Furthermore, and what often seems to be neglected, searching for housing often takes place through network contacts. Therefore, it is crucial to build and develop new migrants and refugees’ networks of contacts as soon as possible. Initiatives such as a mentoring project with pairwise matches between a mentee (newly arrived migrant) and a mentor (volunteer) can definitely help.[10] Most importantly, all efforts to preserve the still low degree of residential segregation are worth supporting. Less segregation means more contact between newly arrived migrants and the resident population. Thus, newly established social housing projects should be carefully designed to prevent ghettoization such as exists in the United States and in European countries such as France and Belgium. Germany should be aware of its current favorable condition of relatively well-integrated (unsegregated) urban regions. The legal approach of relaxing anti-discrimination laws for private landlords might be the price to pay to prevent more pronounced segregation. The current research has shown that there is a moderate tendency for taste-based discrimination that most probably cannot be erased by an anti-discrimination law – or, to put it differently, some things have not changed.

Prof. Dr. Thomas Hinz is a DAAD/AGI Research Fellow from May 1 to June 30, 2016. He is a professor of sociology and empirical social research at the University of Konstanz, Germany.

[1] Becker, G. S. (1971): The Economics of Discrimination. The University of Chicago Press (first published in 1957).

[2] Lower numbers represent a more even distribution of racial/ethnic groups across regional units (i.e., less segregation). For many methodological reasons, these numbers can only provide rough estimates for the degree of residential segregation. The indices are calculated groupwise for each race/ethnic group using white resp. German as the reference. As the report of Iceland (2014) clearly indicates there are further pitfalls when comparing the index values.

[3] Alba, R. and Foner, N. (2015): Immigration and the Challenges of Integration in North America and Western Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

[4] Beauftragte für Migration (2012): 9. Bericht der Beauftragten der Bundesregierung für Migration, Flüchtlinge und Integration über die Lage der Ausländerinnen und Ausländer in Deutschland. Die Beauftragte der Bundesregierung für Migration, Flüchtlinge und Integration: Berlin.

Will, G. (2003): National Analytical Study on Housing. RAXEN Focal Point for Germany. RAXEN 4 Report to the European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia (EUMC). European Forum for Migration Studies: Bamberg.

[5] Drever, A.I. and Clark, W.A.V. (2002): Gaining Access to Housing in Germany: The Foreign-Minority Experience. Urban Studies 39; 2439-2453.

Harrison, M., Law, I. and Phillips, D. Migrants (2005): Minorities and Housing: Exclusion, Discrimination and Anti-Discrimination in 15 Member States of the European Union. European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia.

[6] Members of the team were Laura Schmid, Thorsten Berndt, Katrin Auspurg and the author. The project was funded by the DFG (Hi 680/6-1). See Auspurg, K., Hinz, T. and Schmid, L. (2016): Contexts and Conditions of Ethnic Discrimination: Evidence from a Field Experiment in a German Housing Market. Konstanz. Further and more recent data were collected by Katrin Auspurg and Andreas Schneck at the Ludwig-Maximilian-University Munich.

[7] Heckman, J.J. (1982): Detecting Discrimination. The Journal of Economic Perspectives (12): 101-116.

[8] Defined as the difference in response rates.

[9] Fick, Patrick, Wöhler, Thomas, Diehl, Claudia and Hinz, Thomas (2015), Integration gelungen? Die fünf größten Zuwanderergruppen in Baden-Württemberg im Generationenvergleich. Stuttgart: Ministerium für Integration.