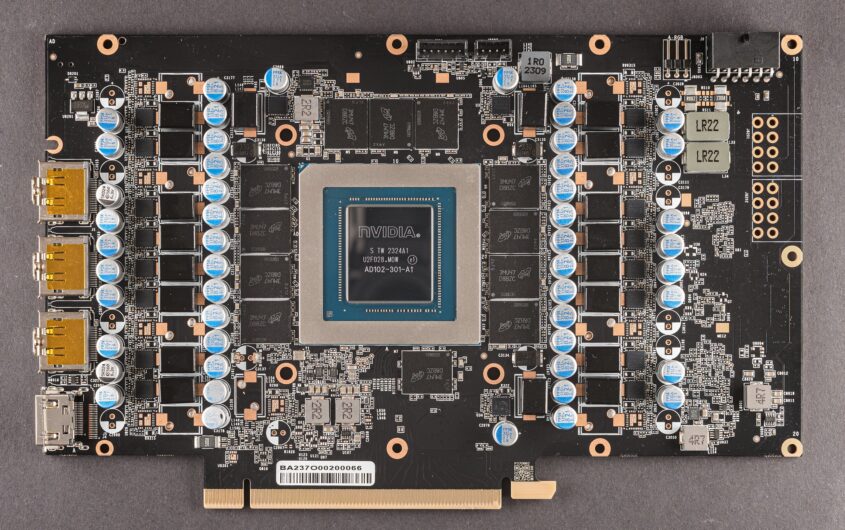

Fritzchens Fritz via Flickr

Transatlantic Export Control Cooperation beyond 2024

Tobias Gehrke

European Council on Foreign Relations

Tobias Gehrke was a Marie Curie Fellow at AICGS in December 2019 - January 2020. He is a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, based in the Berlin office. He covers geoeconomics, focusing on economic security, European economic strategy, and great power competition in the global economy. He was a Research Fellow at the Egmont: Royal Institute for International Relations in Brussels, where he worked in the Europe in the World Program. He is also a doctoral scholarship beneficiary at Ghent University as part of the EU-funded Horizon2020 Marie Curie research project ‘EU Trade & Investment Policy’ (EUTIP).

Mr. Gehrke's research focuses on geoeconomic developments in the global economic order, with particular focus on the European Union’s economic statecraft through its trade, investment, and other regulatory policies. He regularly writes and comments on EU trade policy, Great Power geoeconomic competition, transatlantic and EU-China economic affairs, connectivity, and Europe’s economic statecraft.

He previously joined the EU Commission’s DG Trade USA & Canada unit as on a professional secondment and was a Visiting PhD fellow at the National University of Singapore (NUS) and at Nottingham University. Prior to joining the Egmont Institute, he gained experience the Transatlantic Relations program of the German Council on Foreign Relations in Berlin and the private legal sector. Tobias holds an MSc in International Relations from the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (NL) and an LLM in International Economic Law from the University of Kent (UK).

Yixiang Xu

China Fellow; Program Officer, Geoeconomics

Yixiang Xu is the China Fellow and Program Officer, Geoeconomics at AGI, leading the Institute’s work on U.S. and German relations with China. He has written extensively on Sino-EU and Sino-German relations, transatlantic cooperation on China policy, Sino-U.S. great power competition, China's Belt-and-Road Initiative and its implications for Germany and the U.S., Chinese engagement in Central and Eastern Europe, foreign investment screening, EU and U.S. strategies for global infrastructure investment, 5G supply chain and infrastructure security, and the future of Artificial Intelligence. His written contributions have been published by institutes including The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, The United States Institute of Peace, and The Asia Society's Center for U.S.-China Relations. He has spoken on China's role in transatlantic relations at various seminars and international conferences in China, Germany, and the U.S.

Mr. Xu received his MA in International Political Economy from The Josef Korbel School of International Studies at The University of Denver and his BA in Linguistics and Classics from The University of Pittsburgh. He is an alumnus of the Bucerius Summer School on Global Governance, the Global Bridges European-American Young Leaders Conference, and the Brussels Forum's Young Professionals Summit. Mr. Xu also studied in China, Germany, Israel, Italy, and the UK and speaks Mandarin Chinese, German, and Russian.

__

A new U.S. administration and Congress are imminent. With them, the Biden administration’s diplomatic efforts to construct a new allied export control agenda are on the line. Three scenarios highlight how things could change.

The transatlantic partnership has been evolving to address economic and national security threats posed by China, with technology controls taking center stage. In recent years, U.S. export controls have shifted from targeting distinctly military-related items to becoming the leading tool for managing strategic competition with China more broadly. Europe, too, has adapted its approach, increasingly using export controls in response to emerging technology threats and as a tool of economic statecraft targeting the Russian economy following the invasion of Ukraine.

Despite this broad strategic convergence, transatlantic cooperation on export controls remains fragile. The Biden administration’s swift and sometimes unilateral actions in restricting China’s access to advanced semiconductor equipment have created tension with European allies. Additionally, many European policymakers cling to the idea of export controls chiefly addressing the risk of sensitive technologies falling into military hands. In their view, U.S. export controls often blur the lines by addressing economic and commercial threats—such as China’s industrial dominance through unfair practices. This misalignment of what is in and what is out of national security is challenging further alignment.

And yet, the Biden administration has been, broadly speaking, successful in aligning U.S. and EU technology control agendas. This success relied on extensive and resource-intensive diplomacy, working closely with member states and businesses on details and sensitivities to overcome political barriers. Yet, with upcoming U.S. elections, this balance may be disturbed and could change the foundations of transatlantic policy coordination. We foresee three potential scenarios post-election that could affect this balance.

Scenario One: Row, Row, Row Your Boat

A transition from the Biden-Harris administration to a Harris-Walz administration would avoid aggressive trade policies outlined by the Trump campaign, such as blanket tariffs on allies and foes while continuing to focus on outcompeting China using all available tools.

For instance, the Biden administration has already been considering measures to address China’s growing dominance as the leading producer of legacy chips (over 28nm process nodes) and the risk of overcapacities flooding global markets. A Harris administration could take this up and consider import restrictions, entity sanctions, or further export controls.

In the transatlantic arena, Harris would likely continue methodical diplomacy with the EU and remain sensitive to the bloc’s opposition to decoupling as an official characterization of economic policy toward China. As is the case during the Biden term, debates over the geopolitical consequences of expanding technology controls would likely stay behind closed doors.

A “stable decoupling” from China by a Harris administration following in its predecessor’s footsteps would maintain a sense of predictable stability. However, a bipartisan aversion to free trade deals and the new Washington normal of prioritizing U.S. manufacturing and domestic employment would limit the Harris administration’s ability to offer the EU meaningful carrots for their convergence on export controls.

A renewal (or re-invention) of the U.S.-EU Trade and Technology Council (TTC), particularly on technology security, could well be in the cards. Creative approaches, such as limited trade deals in exchange for export control alignment or exemptions from certain export restrictions (like the Foreign-Produced Direct Product Rule), may also be explored.

Even if other trade irritants remain, Washington would likely continue to work with key EU member states to build plurilateral export control regimes around specific technologies including AI, quantum, and biotechnology, as well as refining a shared framework for economic security in the G7.

Scenario 2: When The Music Stops

If former President Trump wins a second term, his administration—along with hawkish congressional Republicans—would likely push for a more aggressive decoupling from China, particularly in critical technologies. They would likely abandon the Biden administration’s “small yard, high fence” approach, which aims to control only the most sensitive and military-relevant technologies while leaving other trade free. Key figures in a Trump administration may believe that the United States needs stronger support from the EU to enforce its expanded export controls—support that needs to be pressed. Conservative think tanks such as the Heritage Foundation have already laid out policy blueprints, advocating for unilaterally tightening export controls and expanding the list of restricted technologies. Republican lawmakers, critical of the Department of Commerce’s perceived leniency, have proposed legislation to expand and expedite control enforcement without waiting for allied consensus.

Potential success or failure depends on the transatlantic partners’ ability to account for each other’s policy priorities and sensitivities across a broad range of issues from national security to global trade to domestic economics.

A second Trump administration may also push for bilateral export control agreements with individual European countries, similar to the semiconductor equipment deals with the Netherlands and Japan. Republican leaders have called for expanding these agreements to cover emerging technologies such as AI, quantum computing, and biotechnology. EU countries, including Germany, France, Spain, or Finland, could be in scope.

While Trump’s past use of transactional diplomacy might suggest some incentives for EU cooperation, it is uncertain how far his administration would go in pressing leverage over European allies in the export control arena. Though Republican leaders stress the importance of allied cooperation, few indicators exist that show they are willing to invest as heavily in these relationships as the Biden administration has. If an atmosphere of pragmatic, albeit highly transactional, cooperation exists between Washington and Brussels, it is conceivable that a President Trump would refrain from the threat of imposing tariffs on EU imports and even offer certain incentives.

Scenario 3: Ain’t No Sunshine

In this scenario, a second Trump presidency could signal a radical shift in U.S. trade policy. Senior Republican hardliners may push for aggressive tariffs on Chinese imports, potentially repealing China’s permanent normal trade status and even imposing blanket tariffs on all foreign imports of 10 to 20 percent. A Trump administration could also target Chinese national champions like CATL with sanctions, which could disrupt clean tech supply chains globally. Such measures could severely harm transatlantic relations, prompting the EU to prepare counter-tariffs and potentially use tools like the anti-coercion instrument to respond. It would also likely add fuel to Europe’s still simmering relationship with China.

In this contentious scenario, meaningful transatlantic cooperation on export controls may be limited to the bare minimum required by existing security agreements. Progress, then, could very well depend on security-oriented cooperation centered around NATO and its development of an emerging and disruptive technologies strategy (EDT), which covers risk assessment and military applications in domains including AI and quantum technologies. These developments, however, would scarcely bring the benefits of strategic considerations on economic resilience.

Despite these challenges, the underlying rationale for transatlantic export control cooperation would remain relevant, especially in the context of managing China’s growing influence. The United States will continue to seek EU cooperation on export controls, though a growing focus on its industrial competitivness and parallel efforts to push out Chinese-made technologies may see Europe demand more positive elements of cooperation.

The Potential for Transatlantic Cooperation

The level of synergy on transatlantic export controls will be shaped by several factors. First, the increasing use of extraterritorial controls by Washington could strengthen those voices in Europe seeking a more unified and autonomous approach to export controls. Second, China is intensifying its control over tech-related outflows, aiming to limit foreign access and protect key innovations as domestic firms advance up the value chain. An acceleration of this dynamic could prompt more aligned controls between the United States and the EU. Finally, Beijing’s foreign and security policy moves that clearly confront European values and strategic interests, for example, a Chinese military operation against Taiwan or the formalization of Sino-Russian barter trade, could introduce new dynamics that strengthen transatlantic unity but still present major challenges toward achieving export control alignment. These elements will determine the overall potential for cooperation in managing strategic competition with China.

These factors point to some fundamental developments in national and economic security that demand reinvigorated and sometimes new approaches to export control. While both the EU and the United States benefit from a more closely aligned export control regime, a new U.S. administration brings opportunities and challenges alike. What is clear is that potential success or failure depends on the transatlantic partners’ ability to account for each other’s policy priorities and sensitivities across a broad range of issues from national security to global trade to domestic economics.