The Two-Letter Word Leaders are Letting Define the Transatlantic Relationship: 5G

Sarah Lohmann

Dr. Sarah Lohmann is Non-Resident Fellow with the American-German Institute. Dr. Lohmann is an Acting Assistant Professor in the Henry M. Jackson School for International Studies and a Visiting Professor at the U.S. Army War College. Her current teaching and research focus is on cyber and energy security and NATO policy, and she is currently a co-lead for a NATO project on “Energy Security in an Era of Hybrid Warfare”. She joins the Jackson School from UW’s Communications Leadership faculty, where she teaches on emerging technology, big data and disinformation. Previously, she served as the Senior Cyber Fellow with the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies at Johns Hopkins University, where she managed projects which aimed to increase agreement between Germany and the United States on improving cybersecurity and creating cybernorms.

Starting in 2010, Dr. Lohmann served as a university instructor at the Universität der Bundeswehr in Munich, where she taught cybersecurity policy, international human rights, and political science. She achieved her doctorate in political science there in 2013, when she became a senior researcher working for the political science department.

Prior to her tenure at the Universität der Bundeswehr, Dr. Lohmann was a press spokeswoman for the U.S. Department of State for human rights as well as for the Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs (MEPI). Before her government service, she was a journalist and Fulbright scholar. She has been published in multiple books, including a handbook on digital transformation, Redesigning Organizations: Concepts for the Connected Society (Springer, 2020), and has written over a thousand articles in international press outlets.

If last year’s Munich Security Conference (MSC) marked the very public breakup of the United States’ relationship with Europe, this year’s stage message was that Europe had moved on, for better or worse. Appearing in a European Union hoodie sweatshirt to kick off the conference, Amb. Wolfgang Ischinger warned, “I am personally really worried that many of you appear to come here to talk not to each other, but about each other.”

What to do when the transatlantic relationship is in a state of bankruptcy, America is focused on domestic concerns, and Europe’s infrastructure and defense capabilities are lacking? Calling trust the “currency of diplomacy,” Amb. Ischinger called on the leaders gathered in the room to take responsibility and address the challenges together. For leaders sitting in the rows of the main conference hall representing superpowers—waxing or waning—the call went unheeded. Yet it is perhaps exactly in that area where friendly friction had been growing in past weeks that there is a glimmer of hope for uniting old NATO allies.

The discussion around whether the Chinese company Huawei should be given contracts to build the fifth generation (5G) of mobile cellular technology infrastructure across Europe by 2025 was supposed to stay a side-conversation to the conference, really. The Munich stage is reserved for discussing security concerns of global proportions. But that little two-letter word had ministries across the alliance engaged in behind-closed-doors power struggles with each other in the weeks leading up to the conference, with heads of state having to release defining statements on the issue. Now here it was, exploding onto the world stage, dividing “East” from “West,” good from evil, the secure from the insecure.

That little two-letter word had ministries across the alliance engaged in behind-closed-doors power struggles with each other in the weeks leading up to the conference.

“We cannot ensure the defense of the West if our allies grow dependent on the East,” U.S. Vice President Mike Pence told the audience at Bayerischer Hof. “The United States has also been very clear with our security partners on the threat posed by Huawei and other Chinese telecom companies, as Chinese law requires them to provide Beijing’s vast security apparatus with access to any data that touches their network or equipment.”

In fairness, the complaint that if Huawei becomes the company to have a monopoly of contracts on building the telecommunications network in countries throughout Europe, there should be concern that Europeans—and their allies—will be subject to espionage has been convincingly argued by those who should know. The head of Britain’s foreign intelligence service, Alex Younger, has expressed his concerns and the UK’s Five Eyes intelligence-sharing allies, including the United States, Australia, and New Zealand, have all banned Huawei from providing technology for their 5G networks due to “significant network security risk.”

Long before Vice President Pence took the stage, German chancellor Angela Merkel had publicly stated that any awarding of a 5G contract to Huawei must be coupled with guarantees that any data flowing through their network would not be handed over to the state, and that the company would enable a violation of intellectual property. While a report by Germany’s BDI industry network calls for a more cautious approach to China, the trade group’s president has warned against carte blanche banning Huawei from bidding, saying this could interfere with free trade and cause China to boycott German bids in return. But as Europe lags behind the United States in its 5G capabilities, Germany has seen itself with little choice but to keep talks with China ongoing, and Chancellor Merkel is currently working to cut a no-spy deal with China.

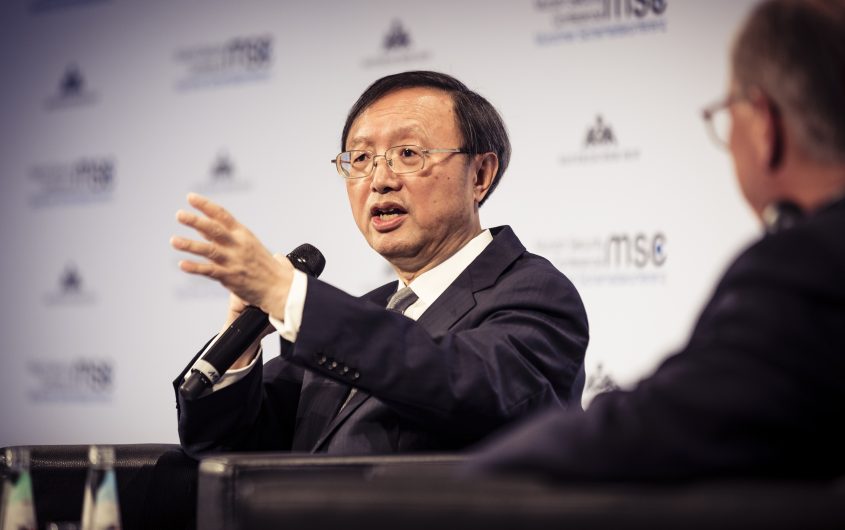

As for China, the CPC’s message to the world came through loud and clear at the MSC weekend: “I wish Americans would have a little more confidence in themselves and be more respectful to other people, people in the so-called Old World,” China’s CPC Central Committee Political Bureau Representative Yang Jiechi responded to Vice President Pence. “Huawei as a company is cooperating very closely with European countries […] Chinese law does not require its companies to install backdoors or collect intelligence.”

So what is the issue? There are three main concerns being voiced among NATO countries:

1.) espionage risks,

2.) economic and political concerns, and

3.) threat of civilian infrastructure being compromised.

Espionage

The NSA and other intelligence agencies have warned of increased chances of espionage while using Huawei technology. Not all countries are convinced this is a problem limited to Huawei. The fact is that 5G technology, which defacto would enable massive volumes of data to flow and connect through its networks, could allow for mass data collection and espionage without being detected due to the very nature of its configuration. The question then becomes whether a nation state feels more comfortable with American or European suppliers of this technology.

In addition, a country must be aware that if it chooses a Chinese company, that company will be subject to China’s laws, even if on European soil. China’s Cybersecurity Law of June 2017 requires network operators to store data on servers in China, which is subject to government control, or to pay companies such as Huawei to be the local service provider. It requires the network operators to further cooperate with Chinese security and give them access to data if requested for the purpose of strengthening cybersecurity.

Economic and Political Concerns

The second question addresses China’s rising dominance as an economic and political power on the world stage, and what impact this is having on the countries using its infrastructure. According to a Carnegie study, if Europe invested €56.6 billion in 5G networks it could receive €113.3 billion in economic benefits annually and create 2.3 million new jobs by 2025.

By contrast, China’s financing of its infrastructure projects is currently giving cause for concern. Huawei is only one cog in the wheel. The Chinese, with their Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which was launched in 2013, have long-term goals. The BRI aims to connect 64 countries with shared infrastructure, across three continents, tapping into 30 percent of GDP world-wide. The Chinese Development Bank says it has set aside $900 billion for 900 projects.

Yet five years on, debt has skyrocketed in the Balkan and Eastern European countries taking BRI loans for their rail and road initiatives, and reports of lack of transparency in spending, and compromises on social, fiscal, and environmental sustainability issues continue. State-owned companies offering large loans with state backing continue to challenge an open procurement process.

Civilian Infrastructure Threat

German security agencies have said that if Europe continues to rely on easily hackable providers such as Huawei for a new 5G network, it could put its power grid at risk, and put valuable information in the hands of the Chinese. Because 5G can improve the efficiency of grid networks or improve water distribution through the use of the Internet of Things (IoT), how and who builds the infrastructure matters.

Perhaps it doesn’t matter if there was, yet again, saber-rattling on the stage of the Munich Security Conference that February weekend. In the rooms beyond the main conference hall in the Bayerischer Hof, many new transatlantic initiatives were being announced to tackle just such issues. The key to their success, and the current global challenge to the transatlantic relationship, is if Europe and North America will define their own long-term innovation and infrastructure initiative for the twenty-first century according to the values of free trade, with transparent procurement and spending processes, protection of privacy, and a strong civil society. The alternative in the wake of a lack of transatlantic unity and inaction, is to let other actors define innovation’s next steps for us, and to live with the consequences if they do.