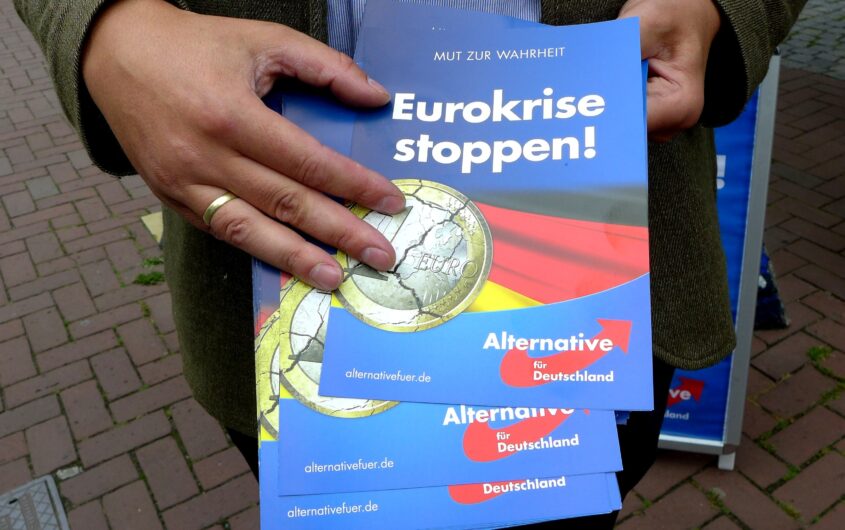

Oxfordian Kissuth via Wikimedia Commons

No Alternative

Hubertus Bardt

German Economic Institute

Prof. Dr. Hubertus Bardt is Managing Director at the Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft, Köln (German Economic Institute, IW), the leading private economic research institute in Germany. Since 2022, he is an honorary professor at the Heinrich Heine University in Düsseldorf.

He studied economics and business administration in Marburg and Hagen and received his doctorate in economics from the Philipps University Marburg. He joined the German Economic Institute in 2000 and has been head of Research Unit Environment, Energy, Resources from 2005 to 2014. His current research focuses on climate and resource policy, industrial policy and defense economics.

Matthias Diermeier

German Economic Institute

Dr. Matthias Diermeier is the head of the research unit democracy, society, market economy at the German Economic Institute (IW). His research focuses on political economy, voting behavior and the welfare state. The goal of his research is to provide solutions to bridge gaps within societies and to answer the rising threat to liberal democracy from the populist right. In his PhD dissertation at the University of Duisburg-Essen in political sciences, he worked intensively on the economic drivers behind the rise of the German AfD. He holds a master’s degree in economics from the University of Zurich, with specialization in Political Economics, and a bachelor’s degree in Economics from the University of St. Gallen. He has also studied at the Sciences Po Paris and Universidad de San Andrés, Buenos Aires.

The German economy is currently in the midst of a structural crisis, marked by prolonged stagnation and rising unemployment. A mix of high taxes and strict regulations has created difficult conditions for investment. Mounting Chinese competition, growing protectionism, the challenges posed by demographic aging, and an ambitious climate policy have only deepened the strain. While the previous and the current governments have struggled to improve business conditions and restore confidence, some voices believe a turn toward the far-right Alternative für Deutschland (Alternative for Germany, AfD) could be a conceivable option to overcome economic distress.

Typically for parties of its kind across Europe, the AfD has built its political identity on fierce opposition to immigration and embraces a strong anti-establishment sentiment. In addition, it campaigns against climate action, pandemic-related restrictions, and military or financial support of Ukraine. In many respects, the party shows clear parallels to the MAGA movement and the Trump administration in the United States. Therefore, it comes as no surprise that the AfD, like other European far-right parties, is supported publicly by Elon Musk, Vice President JD Vance, and other prominent figures from the MAGA camp.

For historical reasons, far-right parties in Germany have traditionally been contained by a strict cordon sanitaire—one that has kept their predecessors on the margins of civil society, the media, and the political establishment. In 2013, prominent economists in the German tradition of social market economy founded the new party, lending it a foothold in the political sphere. From the start, the party mobilized around a culturally conservative and economically liberal opposition to the euro and a strict resistance to bailout measures for Greece and other struggling eurozone countries. As a result, Euroskepticism was linked to a market-oriented economic policy agenda. Populist and nativist elements were introduced quickly and later compounded by opposition to pandemic restrictions, vaccine mandates, and climate action. The early anti-euro pro-market party transformed into a fully-fledged populist radical-right party, displaying many similarities to the MAGA movement. The party’s early founders eventually left and unsuccessfully tried to establish new culturally conservative and economically liberal parties and movements.

The AfD’s economic roots continue to resonate in the party. The mix of advocating market economic reforms while opening the door to Euroskeptic populism remains visible within the AfD’s nationalist-populist agenda. Opposing the government’s economic policy during an economic crisis by stressing the need for market-based reforms appeals to voters beyond its core electorate. Centrist and conservative voters would ordinarily shy away from populist and nationalist anti-establishment rhetoric, yet they share the intuition that the government is failing to deliver on the economy.

Cutting taxes is a central element of the AfD’s economic policy proposals. The tax relief proposed in the election campaign 2025 adds up to 181 billion euros (211 billion USD) annually. This was by far the highest reduction proposed by any party in the Bundestag. While such measures sound business friendly and reduced tax rates are actually urgent to improve investment conditions in Germany, these promises also reveal a lack of credibility: the party has no plan to close or at least to reduce the resulting budget deficit.

While some policy proposals are either unrealistic or ignore pressing demographic or climate problems, other targets of the party are economically dangerous.

The AfD advocates for lower taxes but at the same time proposes a massive increase in publicly funded pension spending. Actually addressing the challenges of an aging population will require adjustments to the pension system to prevent employers and workers from facing sharply higher future contributions. While the proposed tax cuts are meant to attract the business community and the wealthier part of the population, generous social policy proposals court the elderly, whose share of the electorate is growing.

The AfD’s superficial approach to challenges also extends to its energy and climate policy. Framing climate change as purely ideological allows the party to promise deregulation and lower energy prices. It also advocates a return to Russian fossil energy supplies, which would undermine Germany’s efforts to strengthen energy security in a geopolitically unstable environment.

While these policy proposals are either unrealistic or ignore pressing demographic or climate problems, other targets of the party are economically dangerous. Since the AfD started as a Euroskeptic party, it has consistently positioned itself against what it portrays as an overreaching “bureaucratic monster.” Basically, the party wants to replace the European Union with a much looser alliance of European nation-states and abolish the euro as a supranational currency. This would endanger frictionless transaction within the single European market and end most of European integration. Indeed, the EU can be criticized for its complexity and bureaucracy, but it replaces twenty-seven national systems with a single EU-wide approach. Reverting to the national level would recreate trade barriers between the member states, hamper growth perspectives, and shrink Europe’s role on a global stage.

For Germany’s export-oriented economy, a “Dexit” would have disastrous consequences. Empirical modelling indicates that five years after a potential “Dexit”-decision, GDP would be 5.5 percent lower than if the country remained within the eurozone. At the same time, approximately 2.5 million jobs would be put at risk. Since Germany’s exit from the eurozone would probably destroy the common currency and the European Union, the potential economic risks are probably even higher. In addition, significant losses in the other member states would be inevitable. Playing with the idea of leaving the euro or the EU must be considered irresponsible—not only politically but also economically.

The ideological core of the far-right AfD is its nativist stance against immigration. The high influx of refugees roughly ten years ago proved to be a catalyst for the AfD’s rise in popularity. The party couples welfare-chauvinist policies with demands for “remigration,” aiming to make Germany less attractive for immigration by reducing social benefits or by enforcing deportations. Again, clear parallels can be drawn to the United States.

Once again, such a position comes at economic costs. Due to demographic aging, skilled migration will be crucial for sustaining prosperity. Qualified migrants are needed to replace the Germans who were never born. Portraying Germany (or even some of its regions) as a country hostile to foreigners is already harming the country’s attractiveness on the international labor markets. Once again, actually implementing the AfD policy agenda would pose an even greater risk for future prosperity.

For some businesses and a segment of the electorate, the AfD’s economic policy agenda, pitched against a struggling coalition in the midst of prolonged stagnation, may sound attractive. However, the party is overpromising while ignoring real challenges. It poses a massive risk for prosperity by deterring qualified immigrants and risking European integration. The AfD is no alternative for the problems of Germany’s economic policy.