German Federal Archives via Wikimedia Commons

Forty Years After Forty Years After

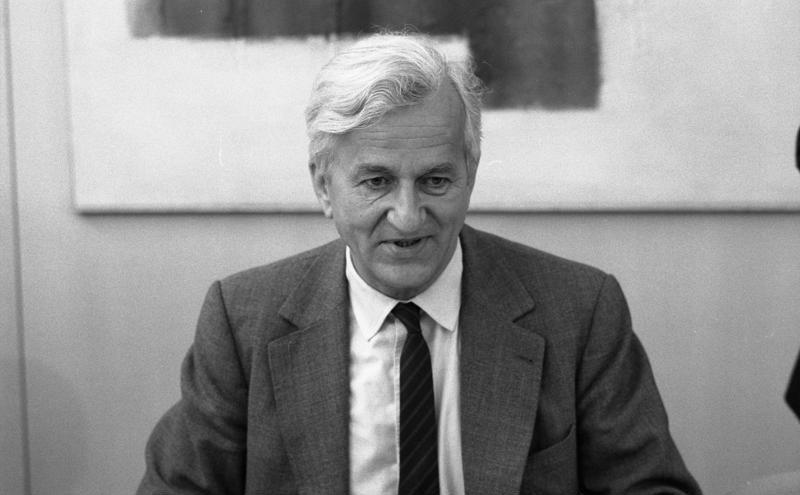

Eric Langenbacher

Senior Fellow; Director, Society, Culture & Politics Program

Dr. Eric Langenbacher is a Senior Fellow and Director of the Society, Culture & Politics Program at AICGS.

Dr. Langenbacher studied in Canada before completing his PhD in Georgetown University’s Government Department in 2002. His research interests include collective memory, political culture, and electoral politics in Germany and Europe. Recent publications include the edited volumes Twilight of the Merkel Era: Power and Politics in Germany after the 2017 Bundestag Election (2019), The Merkel Republic: The 2013 Bundestag Election and its Consequences (2015), Dynamics of Memory and Identity in Contemporary Europe (co-edited with Ruth Wittlinger and Bill Niven, 2013), Power and the Past: Collective Memory and International Relations (co-edited with Yossi Shain, 2010), and From the Bonn to the Berlin Republic: Germany at the Twentieth Anniversary of Unification (co-edited with Jeffrey J. Anderson, 2010). With David Conradt, he is also the author of The German Polity, 10th and 11th edition (2013, 2017).

Dr. Langenbacher remains affiliated with Georgetown University as Teaching Professor and Director of the Honors Program in the Department of Government. He has also taught at George Washington University, Washington College, The University of Navarre, and the Universidad Nacional de General San Martin in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and has given talks across the world. He was selected Faculty Member of the Year by the School of Foreign Service in 2009 and was awarded a Fulbright grant in 1999-2000 and the Hopper Memorial Fellowship at Georgetown in 2000-2001. Since 2005, he has also been Managing Editor of German Politics and Society, which is housed in Georgetown’s BMW Center for German and European Studies. Dr. Langenbacher has also planned and run dozens of short programs for groups from abroad, as well as for the U.S. Departments of State and Defense on a variety of topics pertaining to American and comparative politics, business, culture, and public policy.

__

Reflections on the Eightieth Anniversary of the End of World War II

The 8 of May, 2025, is the eightieth anniversary of the end of World War II in Europe. For decades it was a fraught date in Germany, representing invasion, occupation, and the total destruction of the country, as well as the end of the brutal Nazi dictatorship and the crimes of the Holocaust, peace, and an opportunity to build a new (and better) political system. Even before the establishment of the Federal Republic, Theodor Heuss, soon to become the first president of the FRG noted, “Essentially, this May 8, 1945, remains the most tragic and questionable paradox in history for each of us. Why? Because we were redeemed and destroyed at the same time.”[1]

For many years after 1945, the German population in the West remembered the date as defeat (Niederlage), collapse (Zusammenbruch), or simply as a catastrophe. This was particularly true for the millions of refugees or expellees from the former eastern territories of the country, who were streaming west in the late 1940s. Moreover, until the late 1950s, a large plurality or even majority of Germans living in what became the Federal Republic thought that Nazism was a good idea, badly carried out (mainly citing job creation and social welfare programs). The situation was complicated by the tensions of the early Cold War. The authorities in the German Democratic Republic consistently coded the date as a “day of liberation” (Tag der Befreiung), emphasizing the role of the Soviet Union and Red Army in achieving this outcome. In the West, to overly emphasize liberation would be redolent of communist propaganda during the early postwar decades.

The evaluation of the date slowly began to evolve in the 1970s and 1980s, perhaps due to détente and Ostpolitik, generational change (68ers), and the stability and prosperity that the FRG created, contributing to the thorough delegitimation of the Nazi project. These changing perceptions were evident in the famous speech—some say the best and most impactful speech of the postwar era—of Federal President Richard von Weizsäcker delivered on the fortieth anniversary of the war in 1985, entitled “The 8th of May: 40 Years Later” (Der 8te Mai: 40 Jahre danach). Not only did he codify German memory culture—remembering first the victims of war and tyranny, especially the 6 million Jewish victims—but he also emphasized that it was a day of liberation: “May 8 was a day of liberation. It freed us all from the inhumane system of National Socialist tyranny. For the sake of this liberation, no one will forget the severe suffering that began on May 8 and followed for many people. But we must not see the end of the war as the cause of flight, expulsion, and lack of freedom. Rather, it lies in its beginning and in the beginning of the tyranny that led to the war. We must not separate May 8, 1945, from January 30, 1933.” The larger public was not yet there. That year “liberation” was not really mentioned. 78 percent of Germans thought the date was a warning against war, meanwhile 54 percent thought the press should no longer cover Nazism and the war.[2]

After unification and the addition of 16 million easterners with forty years of “liberation” socialization, however, public opinion soon came to accept such sentiments. On the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the war in 1995, 72 percent of respondents of a stern.de poll saw the date as signifying liberation and 11 percent as defeat. In 2005, 76 percent of Germans saw the date as liberation and 8 percent as defeat; in 2015 89 percent said liberation and in 2020, 77 percent liberation and 5 percent said defeat.

Not only did von Weizsäcker codify German memory culture—remembering first the victims of war and tyranny, especially the 6 million Jewish victims—but he also emphasized that May 8 was a day of liberation.

Fast forwarding to 2025, only 45 percent saw the date as liberation, 15 percent as a defeat and 27 percent as both (admittedly an option not included in the earlier polls). 75 percent blamed the Nazis for the destruction of Germany, yet 57 percent think Germans look too much at the dark side of the country’s history, and 50 percent think there should never be a final line (Schlussstrich) drawn over the past. Only 41 percent think the country’s memory culture strengthens democracy and 67 percent think the Nazi period still shapes the self-understanding of Germany. Finally, 55 percent believe that Germany’s World War II history means that the country has a special moral responsibility for peace and cooperation in the world—even if 88 percent think that successor generations should not be made responsible for what happened in the war.

Certainly, this is only one poll, but these conflicting findings might represent a shift compared to the last few decades. If so, this could be a consequence of the increasing remoteness of the date and that few are still alive with personal memories or experiences of the war and even the immediate postwar years. More worryingly, this could also be a consequence of a right-wing turn in public opinion, an effect of the rise of the Alternative for Germany (AfD), which is currently supported by about a quarter of the electorate. In 2023, AfD co-leader Alice Weidel, defending her decision not to attend a commemorative reception at the Russian Embassy in Berlin stated, “So, to celebrate the defeat of one’s own country with a former occupying power is something I have personally decided—also with my father’s escape story—not to take part in.” There was even more concerning revisionism during the 2025 Bundestag election campaign when in conversation with Elon Musk, Weidel opined that Hitler was not right-wing, but rather a communist.

It will be important to follow the evaluation of this momentous date and Germans’ historical consciousness and memory culture more generally in the challenging years to come. Given some worrying signs such as increased support for the AfD and that party’s more radical historical revisionist tendencies, it is encouraging to see that the new government is investing heavily in democracy promotion and memory culture, which is even a highlighted R&D target in the coalition agreement. But exactly the same amount of time has passed since von Weizsäcker delivered his speech in Bonn that had passed between the end of the war and that date. As a first step, perhaps Germans could be coaxed to re-read this impactful text—forty years after 40 Years After.

[1] Jan-Holger Kirsch, “Wir haben aus der Geschichte gelernt” Der 8. Mai als politischer Gedenktag in Deutschland, (Dokserver des Zentrums für Zeithistorische Forschung Potsdam, 1999), p. 47.

[2] Kirsch, p. 121.