via picryl

What Germany Needs?

Eric Langenbacher

Senior Fellow; Director, Society, Culture & Politics Program

Dr. Eric Langenbacher is a Senior Fellow and Director of the Society, Culture & Politics Program at AICGS.

Dr. Langenbacher studied in Canada before completing his PhD in Georgetown University’s Government Department in 2002. His research interests include collective memory, political culture, and electoral politics in Germany and Europe. Recent publications include the edited volumes Twilight of the Merkel Era: Power and Politics in Germany after the 2017 Bundestag Election (2019), The Merkel Republic: The 2013 Bundestag Election and its Consequences (2015), Dynamics of Memory and Identity in Contemporary Europe (co-edited with Ruth Wittlinger and Bill Niven, 2013), Power and the Past: Collective Memory and International Relations (co-edited with Yossi Shain, 2010), and From the Bonn to the Berlin Republic: Germany at the Twentieth Anniversary of Unification (co-edited with Jeffrey J. Anderson, 2010). With David Conradt, he is also the author of The German Polity, 10th and 11th edition (2013, 2017).

Dr. Langenbacher remains affiliated with Georgetown University as Teaching Professor and Director of the Honors Program in the Department of Government. He has also taught at George Washington University, Washington College, The University of Navarre, and the Universidad Nacional de General San Martin in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and has given talks across the world. He was selected Faculty Member of the Year by the School of Foreign Service in 2009 and was awarded a Fulbright grant in 1999-2000 and the Hopper Memorial Fellowship at Georgetown in 2000-2001. Since 2005, he has also been Managing Editor of German Politics and Society, which is housed in Georgetown’s BMW Center for German and European Studies. Dr. Langenbacher has also planned and run dozens of short programs for groups from abroad, as well as for the U.S. Departments of State and Defense on a variety of topics pertaining to American and comparative politics, business, culture, and public policy.

__

The 2025 CDU/CSU-SPD Coalition Agreement

After the February 23, 2025, Bundestag election, only two majority coalition governments were possible under the Union leadership of Friedrich Merz. Given that an alliance with the far-right populist Alternative for Germany (AfD) was categorically rejected, negotiations commenced in mid-March between the Christian Democratic Union and their Christian Social Union sister party (CDU/CSU) and the Social Democrats (SPD). The main negotiators were Merz and Thorsten Frei (parliamentary manager) for the CDU, Markus Söder (party leader) and Alexander Dobrindt (faction leader) for the CSU, and Lars Klingbeil, Saskia Esken (the party co-leaders), and Matthias Miersch (general secretary) for the SPD. In addition to a larger negotiation committee, there were sixteen working groups (with sixteen members each) working in various policy areas such as digital, state modernization, climate, Europe, and cultural policy.

This protracted process resulted in a 146-page agreement (two pages longer than the 2021 version) made public on April 9. The CDU will ratify the agreement at a special party convention on April 28, and the SPD membership is voting on it between April 15 and 29. There has been some internal opposition in the parties, but especially from the SPD left and its youth organization (Jusos). There were also some disgruntled conservatives who thought that the SPD dominated in the talks, leading Merz to water down or ignore some campaign promises. Presuming that ratification occurs, the new government is set to be sworn in on May 6 about two and a half months after the election (very similar to the timeframe back in 2021).

Always an interesting read, the coalition agreement is a highly detailed governing agenda and course of action for the next government. Indeed, German governments have a good track record of implementing these detailed plans. Even the unstable “traffic light” coalition had a decent record despite in-fighting among the three partners and the full Russian invasion of Ukraine about two months in that upended everything. Entitled “Responsibility for Germany” (Verantwortung für Deutschland), the new agreement has quite a few differences to the 2021 agreement (“Dare More Progress: Alliance for Freedom, Justice, and Sustainability”). In addition to the many policy details, there is much excellent prose, particularly in the preamble. The initial words are: “Germany is facing historic challenges. The policies of the coming years will decisively determine whether we continue to live in a free, secure, just, and prosperous Germany. We are aware of this responsibility and are aligning our actions and policies accordingly.” Other notable turns of phrase include “Our culture is the foundation of our freedom,” “Germany is a cosmopolitan (weltoffenes) land and will remain so,” and “We want to be able to defend ourselves so that we don’t have to defend ourselves.” Actually, the original German is more powerful: “Wir wollen uns verteidigen können, um uns nicht verteidigen zu müssen.”

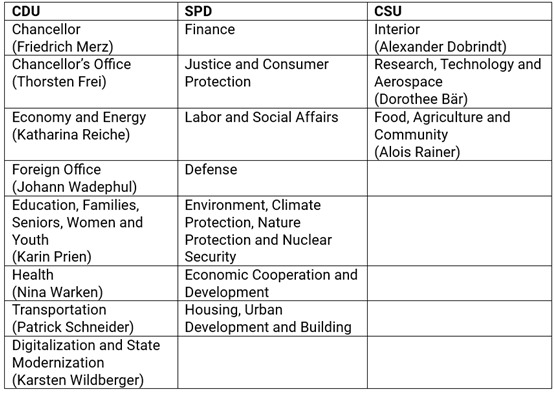

In terms of personnel, the agreement outlines which parties will control the various ministries:

There have been several reorganizations. Community (Heimat) has been moved from interior to food and agriculture; climate has been taken away from the economics ministry (a change the last vice chancellor Green Robert Habeck made); education was added to the family and youth ministry, and research was combined with technology and aerospace (a new specific emphasis). A new ministry of digitalization and state modernization has been created. There are now eighteen cabinet-level positions (and sixteen ministries excluding the chancellor’s office) compared with seventeen in the last government.

The full slate of personnel has not yet been announced. Merz announced the Union ministers on April 28. There are quite a few newcomers and some surprises. Little-known Johann Wadephul will be foreign minister (the first CDU politician to run that portfolio for sixty years) and tech executive Karsten Wildberger will be in charge of digitalization. Karin Prien, the current education minister in Schleswig-Holstein and the first Jewish cabinet member in the history of the Federal Republic will take on that portfolio nationally. State secretaries/ministers were also announced. Serap Güler, Gunther Krichbaum, and Florian Hahn (CSU), all sitting Bundestag members, will be the state ministers in the Foreign Office. Wolfram Weimer is designated to be the minister of state for culture. The choice of a conservative publisher and publicist is already garnering criticism. On the SPD side, the only certainty is that Klingbeil will be the vice chancellor and might also get the powerful finance ministry. Boris Pistorius (long the most popular federal politician) could stay at defense. There will be further negotiations about the assignment of state secretaries/ministers, as well as ambassadorships (particularly to important posts like the United States, where current Ambassador Andreas Michaelis will be leaving in summer 2025). As always, it is a sensitive process to achieve various balances: gender (especially with fewer women in elected office), region (Easterners have been under-represented and North Rhine Westphalia seemingly over-represented), and ideological factions within the catch-all parties.

The actual document has six chapters: economy and labor; finances and state modernization; security, migration, and integration; social cohesion and democracy; foreign policy and Europe; as well as logistics about how decisions will be made and internal disputes settled. There is ample policy detail as well as a profession of values and goals. They want to reduce unemployment while boosting investment and pursuing an “innovation offensive” (100 billion euros). Tax breaks for craft services, a 7 percent tax cut for gastronomy, and support for household-related services are envisioned, as well as subsidies for energy, electric cars, and support for space exploration (putting a German astronaut on the moon). Referencing a “massive budget deficit and debt service” they will consolidate public finances and subject all promises to a strict fiscal test, while also guaranteeing social security (pension levels will be maintained until 2031) and providing tax breaks for childcare. Irregular migration will be curtailed in cooperation with European partners, and resources will be devoted to fighting the root causes behind asylum-seeking and migration. Bureaucracy is to be reduced by 25 percent and the government comprehensively digitalized. There is also a heavy emphasis on education (language classes for migrants, strengthening Erasmus+) and research with the goal to spend 3 percent of GDP especially in strategic R&D fields: health, sustainability, memory culture, security studies, and democracy strengthening. Defense spending will continue to increase, and Ukraine will be “comprehensively” supported.

Overall, it is a centrist—some say cautious—document that avoids the more ambitious or controversial (immigration) campaign pledges. Still, the plan to create a 500-billion-euro infrastructure fund and heightened defense spending—made possible by a lame duck session of the outgoing Bundestag that loosened the so-called “debt brake”—are needed changes to the status quo. There were a few surprises. With the Greens no longer a part of the government, it is noteworthy how much emphasis there is on sustainability in this agreement. This may show how broadly supported green policies are across the political mainstream, or it is a consequence of a deal made in the debt brake vote to secure the Greens’ support for the required two-thirds majority. In contrast to Merz’s comments on election night, the document contains several conciliatory statements towards Trump’s United States, aiming to deepen relations and proclaiming that “Europe and the USA are members in the same community of values.” There were also several more contentious issues that the partners punted on, pledging to create investigative committees to report on a possible increase in the minimum wage or to propose yet another reform to the electoral law.

We shall see how effective the new government is in achieving this joint agenda. Merz is untested in government and has lost support: only 32 percent of Germans now think he is the right person to be chancellor with 60 percent thinking the opposite. The CDU/CSU is down in the polls and in a handful is even being outpolled by the AfD. Even though modifying the debt brake was the right thing to do and will mitigate some of the spending fights that waylaid Olaf Scholz’s coalition, this was a break with long-standing Union policy and campaign promises. Still, Merz and Klingbeil work well together, and the Bavarians seem sufficiently satisfied. The coalition partners clearly understand the gravity of Germany’s situation and the need for effective governance with the war in Ukraine still raging, continuing poor (even worsening) economic performance, and an unpredictable, tariff-loving American superpower.