via picryl

After the State Elections in the East

Dieter Dettke

Georgetown University

Dr. Dieter Dettke is a Non-Resident Fellow at AICGS and Adjunct Professor at Georgetown University.

Dr. Dettke served as the U.S. Representative and Executive Director of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation in Washington from 1985 until 2006 managing a comprehensive program of transatlantic cooperation. In 2006, he joined the German Marshall Fund of the United States as a Transatlantic Fellow and from September 2006 to June 2007, he was a Fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. His most recent book is “Germany Says ‘No’: The Iraq War and the Future of German Foreign and Security Policy,” published by theWoodrow Wilson Center Press and The Johns Hopkins University Press, Washington, DC, and Baltimore, 2009.

Dr. Dettke is a foreign and security policy specialist, author and editor of numerous publications on German, European, and U.S. foreign and security issues.

He studied Law and Political Science in Bonn and Berlin, Germany, and Strasbourg, France and was a Fulbright Scholar at the University of Washington in Seattle in 1967/68.

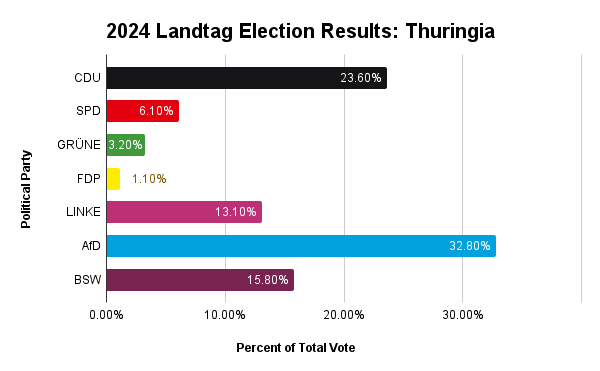

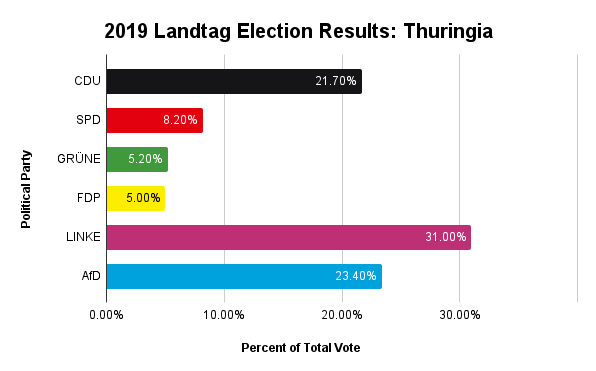

The Risk of a Frozen German Democracy

The election results in the eastern German states of Saxony, Thuringia, and Brandenburg came as a shock to the government in Berlin. Not only did the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) emerge as the strongest political force in Thuringia, but the results for the three parties of the ruling federal coalition (the Social Democrats, Greens, and Free Democrats) came close to a vote of ‘no confidence.’ Support for the Free Democrats (FDP) dropped to one percent in Thuringia and Saxony. With only 0.8 percent in Brandenburg, the FDP is now, politically speaking, an endangered species certainly in the east but potentially also in the 2025 Bundestag elections.

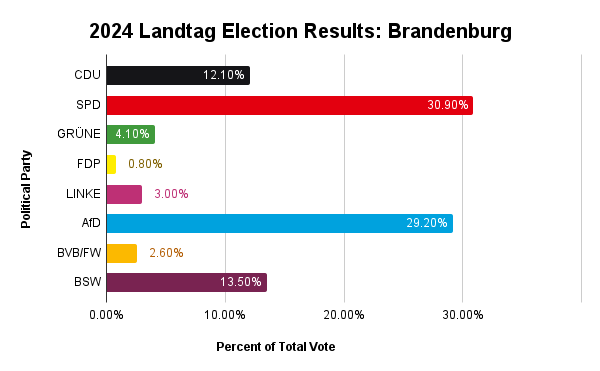

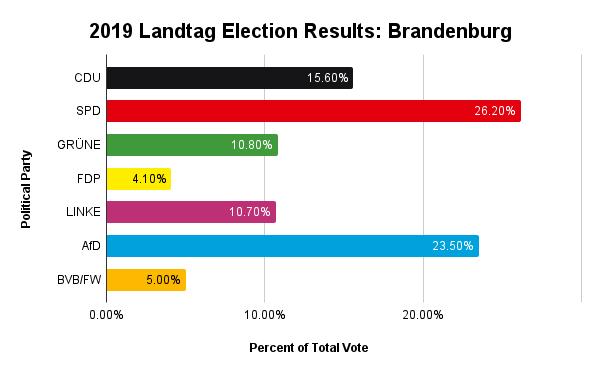

Votes for the Greens fell to under 5 percent in Thuringia and in Brandenburg, and the party barely made it over the 5 percent hurdle in Saxony. The only bright spot for the Social Democrats (SPD) was in Brandenburg, where the party managed to stop the advance of the AfD in a tense battle for a majority. With 30.9 percent, Chancellor Scholz’ party eked out a slim majority over the AfD, which was favored to win here, too. The AfD came in second with 29.2 percent. This success, however, came with hidden costs of the polarization the popular Minister-President of Brandenburg, Dietmar Woidke, used in his election campaign, including threatening to resign if he did not win. Woidke’s strategy absorbed votes from other democratic parties, in particular the Greens and the FDP. The result was ambivalent insofar as it led to a fragmentation of the parties trying to stop the AfD.

The SPD has governed Brandenburg uninterrupted since unification in 1990, but to do so in the future, the current Grand Coalition of SPD and Christian Democrats (CDU) will need a third coalition partner. The two parties together would be one seat short of the necessary absolute majority in the Brandenburg state parliament. Putting together a governing majority will now be exceedingly difficult in all three eastern German states because the AfD gained much political ground at the expense of the liberal democratic parties.

Complicated Coalition Building

Aggravating the fate of the governing coalition of the SPD, FDP, and Greens in Berlin is the fact that a completely new political party, the Alliance Sahra Wagenknecht (Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht or BSW) made it into all three state parliaments in its first attempt and with 16 percent of the votes in Thuringia, even besting Die Linke (The Left), the former political home of Sahra Wagenknecht. She served in the past as Parliamentary Group leader of Die Linke in the German Bundestag. Die Linke was also the party in power in Thuringia since 2014 but ended up with only 13.1 percent of the votes in the recent elections. Today, the BSW is de facto a retort political party, the brainchild of two strong maverick personalities, Sahra Wagenknecht, now a self-proclaimed savior of the Left, and her husband Oskar Lafontaine. He is also a former leader of Die Linke, but his ego was always too big for any political movement he was involved with before, namely the SPD and Die Linke. The main message of the BSW is a right-wing approach to migration and a left-wing agenda of social welfare programs. The foreign policy program is distinctly pro-Russian and anti-Ukraine but masquerading as a party of peace. The BSW also opposes the stationing of American non-nuclear missiles on German soil and threatened to make these positions a condition for entering any coalition at the state level.

Putting together a governing majority in Thuringia after the elections will be exceedingly difficult because of the fragmentation of the political spectrum trying to prevent the AfD from governing the state. The CDU, which achieved 23.6 percent of the votes, will try to create a coalition against the AfD. But to do so the CDU will need not only the support of the SPD and the BSW but also the votes of Die Linke. So far, the CDU has rejected any cooperation with Die Linke due to wide political differences. Similar hurdles exist for any cooperation with the BSW. The only commonality is the opposition to allowing the AfD a position of power in Thuringia.

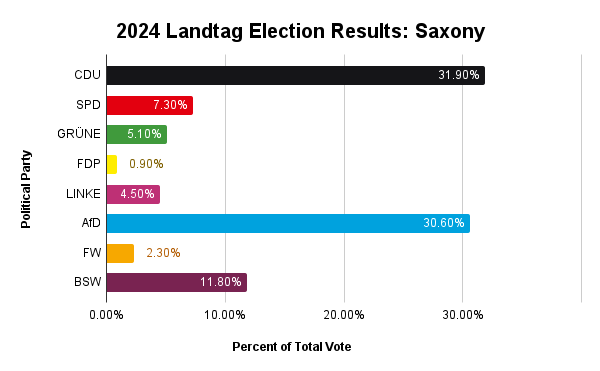

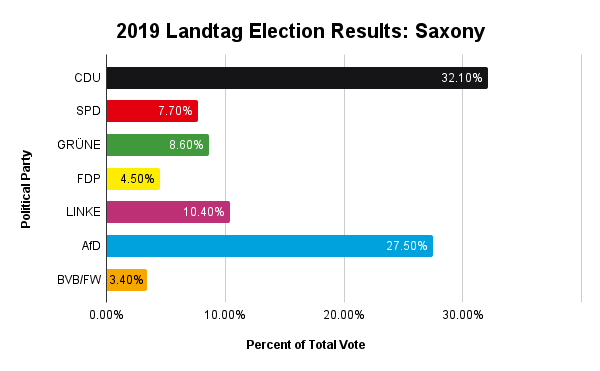

In Saxony, coalition building after the elections will be similarly complicated. Here, the CDU came out first with 31.9 percent followed by the AfD with 30.6 percent. With 4.5 percent, Die Linke did not clear the 5 percent hurdle but will keep its representation in the state parliament with six seats because of the two direct mandates the party won in Leipzig in the last elections. A grand coalition of the CDU and SPD, which formed the government of Saxony in the past, does not have enough seats in the state parliament after the elections. The SPD ended up with only 7.3 percent of the votes in Saxony. The CDU, SPD, and Greens together would also be short of the necessary absolute majority because of the weak support for the Greens. The Greens achieved only 5.1 percent of the votes. The three parties would also need the BSW for a governing majority, a coalition that would then be called the “Blackberry Coalition” (Brombeer-Koalition).

Negotiations to form a governing majority will be difficult if not even impossible because these parties have little in common, except to prevent the AfD from getting stronger. A tolerated minority government, unstable as it would be, could be the only solution.

The Consequences of Fragmentation

The political consequences of governing coalitions in the east dependent on support from the BSW would be dramatic for Chancellor Olaf Scholz. With the opposition of the BSW to supporting Ukraine militarily and rejecting the stationing of American non-nuclear missiles in Germany beginning in 2026, major foreign policy positions of the ruling coalition in Berlin would be exposed to challenges from a coalition partner on the state level. German security policy more generally as well as the country’s leading role in the European Union and the Atlantic Alliance would be exposed to domestic challenges, including dissonance within the coalition. Uncertainty and negative repercussions for the trust and reliability of Germany for neighbors and allies would be unavoidable.

The efforts to stop the advance of the extreme right AfD are understandable in a country with a past that includes the Holocaust and unspeakable war crimes. But simply blocking the AfD from getting into positions of power will undoubtedly increase political polarization. The new risk could be that polarization will come with a high degree of fragmentation of the political spectrum opposing the AfD. The result could be what Ivan Krastev recently diagnosed as a “frozen democracy.”[1]

Fast forward to the 2025 national elections and the problem for today’s unpopular traffic light governing coalition will be that the chances of getting Chancellor Scholz reelected appear rather slim. There are already voices, particularly within the FDP, to leave the coalition even before the 2025 national elections, in which case early elections would most likely take place. A more likely scenario is that the CDU and its Bavarian sister party the Christian Social Union (CSU) will come out as the strongest parties in 2025. Under the present circumstances, however, an absolute majority of the two Christian Democratic parties is highly unlikely (they are currently polling between 30 and 35 percent). If the CDU and CSU win a plurality of votes in 2025, they would need at least one if not even two or more coalition partners. The CDU and CSU alone have little chance of getting enough votes to govern without a partner.

Given the current weakness of the SPD, there might not even be enough votes for another Grand Coalition of the CDU/CSU and SPD. More importantly, with the tendency of the CSU to exclude any coalition with the Greens, should they get enough votes in the next elections, the BSW might end up in the role of delivering the necessary votes for a governing coalition. This would throw German politics back into a serious state of fragmentation that could make governing difficult to the point of immobility—“frozen” in the sense that Ivan Krastev suggested. If this would be the result of trying to keep the AfD out of power, Germany’s liberal democracy could be at risk and create more opportunities for the kind of right-wing extremism liberal democratic parties try to keep out of power positions.

The Challenge of the Extreme-Right AfD

Germany missed an opportunity to create a two-party system like in Great Britain in 1966 when this idea was contemplated within the first Grand Coalition of the CDU/CSU and SPD. Today, polarization is much harder to deal with because of the fragmentation of the group of liberal democratic parties trying to stop the AfD from advancing further. The argument that the success of the AfD in Germany is part of a larger European and even global political trend and, therefore, normal is misleading. The German case for many historical and political reasons is different for its neighbors and for its citizenry. Even if one might argue that the AfD is not the same and not as dangerous as Hitler’s Nazi party, Germany as a liberal democracy, a good European neighbor, and a member of the Atlantic Alliance would come to an end if the AfD would achieve its goal of getting elected to national leadership positions.

The historian Heinrich August Winkler in his important work on the history of Germany as a nation argued that only with unification did Germany fully arrive in the West, and he saw liberal democracy as the ultimate destination for Germany.[2] The challenge of the AfD for Germany is that based on the AfD agenda the country would—like in the past—end up as a central European power without its Western and liberal democratic anchoring. The result would be new instability on the European continent. Germany, Henry Kissinger famously said, is “too big for Europe and too small for the world.” The country achieved its most beneficial geopolitical position as a liberal democracy firmly anchored in the European Union and as a reliable NATO partner. In its current condition, the AfD is even an outlier among the group of right-wing European political parties, so much so that it was removed from the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) Group in the European Parliament.

Mainstreaming the party is impossible today, especially after the triumph in the state elections in the east. A political transformation of the magnitude that Georgia Meloni initiated in Italy cannot be expected from today’s AfD. The party is a threat to liberal democracy and prone to advocate and even use violence against political opponents. Based on its current agenda, the party would systematically undermine the political future of Germany and its economic and political lifeline, the European Union. Its almost suicidal involvement with Putin’s Russia would push Ukraine back into the grand design of Russian imperialism and create a mortal threat for Russia’s European neighbors and Germany. In the end, Germany would end up isolated in Europe and exposed to Russian political and military threats, including possible nuclear blackmail.

Conclusion

The current dilemma of German politics could not come at a more unfortunate moment. Multiple political crises abroad and economic uncertainty at home require forceful political decisions. A concerted action of all liberal democratic parties is urgent. Inaction cannot be the answer. As a matter of self-preservation, Germany should not only try to isolate the AfD at home and in Europe. The German Constitution does have an answer for political parties which put the democratic future of the country at risk.

The Constitutional Court in Karlsruhe can outlaw a political party that supports violence against political opponents and puts the democratic constitution of the country at risk. It would not be the first time that the Constitutional Court has acted against such political parties. The proceedings for the prohibition of political parties are governed by Article 21 (2) of the Basic Law. The article says that “political parties by reason of their aims or the behavior of their adherents, seek to undermine or abolish the free democratic basic order or to endanger the existence of the Federal Republic of Germany must be declared unconstitutional.”

The Bundestag, the Bundesrat, or the Federal Government have legal standing to initiate the proceedings for the prohibition of the AfD at the Constitutional Court. Obviously, such an attempt by either the government or political groups of the Bundestag would be time-consuming and difficult. Legal success is not guaranteed, but beginning proceedings for the prohibition of the AfD could help bring about the kind of transformation of the party necessary to avoid risks for Germany’s democratic future.

[1] See his insightful article “The Rise of Frozen Democracies is Bad News,” Financial Times, September 13, 2024.

[2] Heinrich August Winkler, Der lange Weg nach Westen, Band I und II, (Munich: Verlag C.H.Beck, 2020).