Tobias Nordhausen via Flickr

Electoral Reform in Germany

Sven T. Siefken

Institute for Parliamentary Research, Berlin, and Federal University of Applied Administrative Sciences

Sven T. Siefken is professor of political science at the Federal University of Applied Administrative Sciences and Senior Research Fellow at the Institute for Parliamentary Research (IParl) in Berlin. He is Vice Chair of the Research Committee of Legislative Specialists (RC08) of the International Political Science Association and editor of the German Journal for Parliamentary Affairs (Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen). His current work investigates coalition politics, parliamentary committees and the future of democratic representation. More here: www.siefken.org

Photo credit: APB Tutzing

An End to a Never-ending Story?

On July 30, 2024, the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany ruled that the highly contested electoral reform passed in early 2023 was by and large in line with the constitution. Some details were immediately revised by order of the Court, but the more fundamental changes to the electoral law were approved. This is in line with previous decisions, strengthening the element of proportional representation.[1] Is this the end to a never-ending story of electoral reform?

When the electoral law was passed on March 17, 2023, after a heated debate in the Bundestag,[2] prominent opposition MPs cried “foul play.” Around its first reading in January 2023, Martin Huber (Christian Social Union, CSU) had likened the coalition to thugs that go about limiting democracy in Germany, conducting “organized electoral fraud.” In the second reading, the atmosphere in Parliament got worse with The Left’s (Die Linke) party whip Jan Korte criticizing the coalition for “bigoted arrogance” and an electoral law that has been “snotted down” (hingerotzt). MPs of the Christian Democrats (CDU) and CSU (center-right sister parties) applauded.

The CSU and the CDU had threatened to bring the law to the Court and have its constitutionality checked. Opposition leader Friedrich Merz (CDU) announced that if his party wins in the next election, the new government would reverse the most recent changes. Electoral reform was a very hot political topic, and it remains to be seen if the Constitutional Court decision will have a pacifying effect.

This analysis presents the core of the new electoral law as it stands after the Court decision and as it will be applied for the next Bundestag election, likely to be held in September 2025. It describes the long process that has led to the current situation and discusses its implications. Finally, it shows that the reform does not fundamentally change the logic of political representation in Germany, contrary to what some political actors and observers have argued.

The German Electoral Law as of Summer 2024

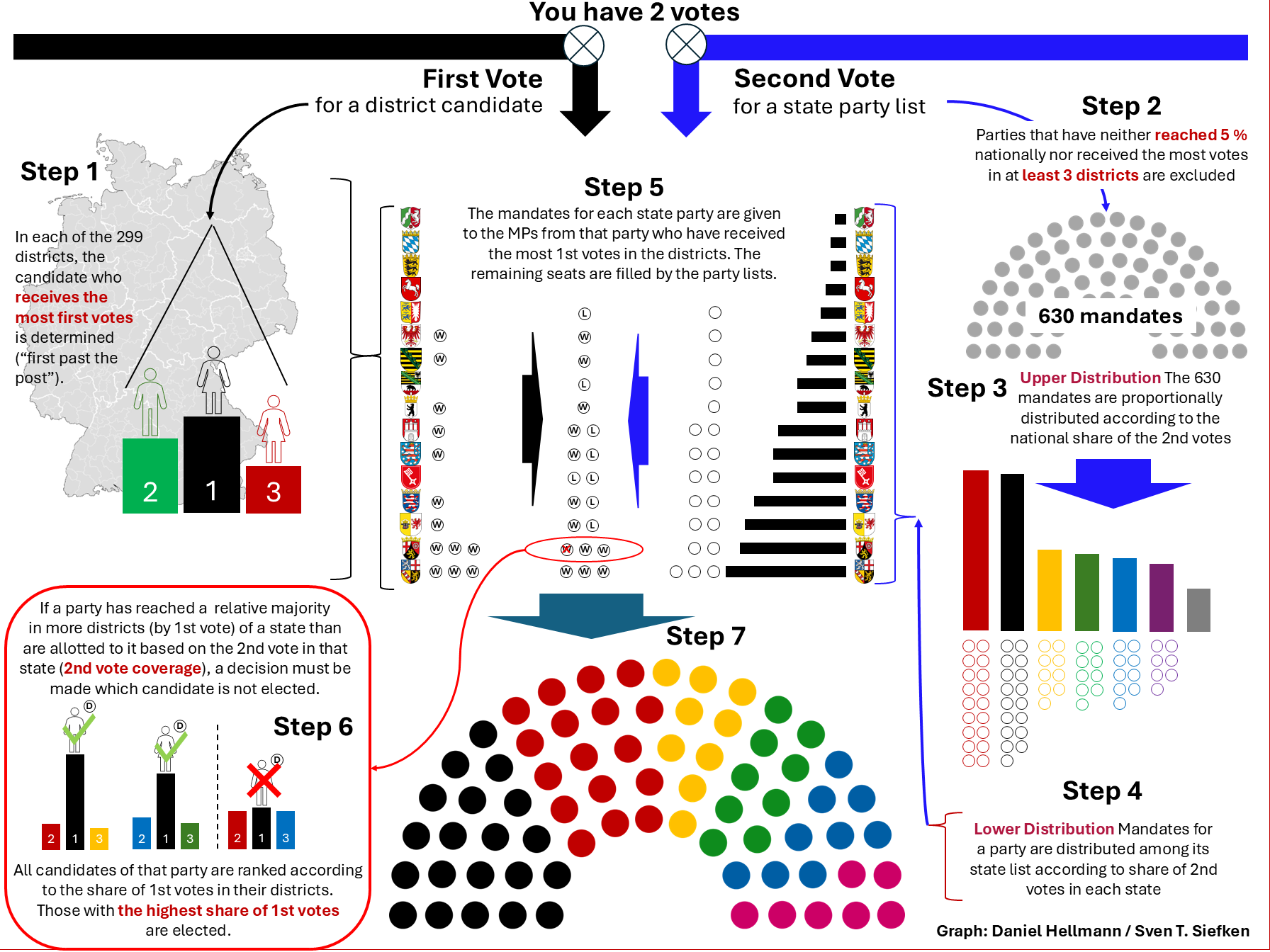

The electoral law is fairly straightforward now: each ballot has two votes, one for a district candidate, the second for a state party list. The future Bundestag has a fixed size of 630 members, and mandates are allotted strictly in proportion to the vote share of all parties that reach at least 5 percent of the votes nationally or win three electoral districts. Candidates who gain the (relative) majority in one of the 299 districts receive the first mandates, the remaining seats for each party are filled according to the order of the party list.

The Long History of the Electoral Law and its Reforms in Germany

The German electoral law has a history of conflict between the parties and repeated consequential decisions of the Constitutional Court. When the Grundgesetz (German Basic Law) was developed in 1948 and 1949 by the Parliamentary Council, the founders of the Federal Republic of Germany could not agree on an electoral law: the newly formed CDU and CSU argued for a majority voting system, whereas the liberal Free Democrats (FDP) and the Social Democratic Party (SPD) were proponents of proportional representation. Make no mistake: electoral laws always have consequences for the distribution of power, and the political parties know it. Those that were arguing for a majority voting system would profit from it, those for proportional representation likewise. Politics and polity cannot be separated on this issue.

Various combinations of those two systems were debated. In the end, the Grundgesetz did not include any details of the electoral law. Instead, its Article 38 lays down the fundamental requirements: Elections have to be general, direct, free, equal, and secret. Details of the electoral system are thus set in a federal law and therefore require a simple majority for changes—not a two-thirds majority as required for amendments to the constitution. The disagreement led to a particular compromise bringing together elements of majority and proportional elections in a system that has become known as personalisiertes Verhältniswahlrecht or personalized proportional representation. Comparative studies often dub it as “mixed member proportional representation” (MMP), but this is misleading as will be discussed below. Political scientists have argued that this electoral law combines “the best of both worlds”[3]—making sure that all relevant groups are represented in Parliament through proportionality and at the same time securing a personal relationship of citizens to their representatives in the district. This system stood as a model for electoral reform across the globe: Japan, Israel, Italy, New Zealand, Bolivia, Venezuela, Scotland, and quite a few others. Yet looking at the particular history of how the German electoral law was invented, one must remember that it was not by “grand design” but by compromise: “the German ‘model’ was as much an ad hoc creation as it was the product of theoretically inspired engineering.”[4]

The fundamentals of this system are based on the proportional representation in parliament of the political parties according to their national vote share. On the ballot, voters can cast two votes: The first is for a district candidate, the second for a party list. If a party gets 20 percent of the second votes nationally it receives 20 percent of the total seats in Parliament. At the same time, there are districts, and in each of them, one MP is chosen by relative majority (by the first vote on the ballot), that is according to the “first past the post” logic. For many years, the number of electoral districts in Germany was 248. After these district seats were allotted by the first vote, parties received mandates according to their national vote share so that overall proportionality would be reached according to the second vote until the “legal size” of the Bundestag (498 mandates) was reached.

After the reunification of Germany (technically the accession of New States to the Federal Republic) district sizes were left untouched. Therefore, as the Republic grew, so did the number of districts, and with them the Bundestag. Since 1990, 328 districts existed; the legal size of Parliament was therefore 656. In 2002, the number of districts was reduced to 299, bringing the legal size down to 598.

However, the real size of the Bundestag has often differed from its legal size—and there was nothing illegal about this. This resulted from the complexities of the German electoral system as well as from changing voting behavior. As “voters began to choose”[5] in Germany, too, they started to increasingly split their two votes on the ballot and selected different parties. As a consequence, the so-called surplus or overhanging mandates (Überhangmandate) occurred in larger numbers than before; but other reasons in electoral math and organization contributed to this, as well: variations in district size and the intermediate calculations based on the vote shares in the federal states. Surplus mandates come about as follows: any MP who received a relative majority in a district had their seat in Parliament secured; nobody could take it away. This could lead to the situation that a party already received more seats in one state according to the first votes than its correct proportional share according to the second vote. In this case, a surplus mandate was granted. The number of surplus mandates grew over the decades, from two (in 1949) to six (1990) and twenty-four (2009). These additional mandates for certain parties—mostly the CSU and the CDU—were in conflict with the constitutional principle of “equal” elections, because it gave more weight to voters who strategically split their votes.

The mathematical operations behind these calculations were complex and could even lead to paradoxical effects. This received broad attention when an MP of the National Democratic Party (NPD) died in 2005. Elections in the district in Dresden were rerun, and it became apparent that the CDU could actually lose one seat in Parliament if it won a certain number of second votes (specifically: between 42,000 and 60,000). In this way, voters casting their ballot for the CDU could cause a mandate loss. Hence, the effect is called negatives Stimmgewicht (negative vote weight). This effect had occurred before in a few cases, but because of this isolated election in one district only, it was all of a sudden visible and even discussed in campaign strategy. This paradox led to a contestation of the electoral law in the Constitutional Court, and the judges deemed the law unconstitutional in 2008, asking for further reform.

The governing coalition of CDU, CSU, and FDP made some adjustments to reduce the chances for overhanging mandates and—under certain conditions—included additional mandates created by remaining votes (Reststimmenmandate). The new law was decided on in September 2011 with the votes of the coalition and against the votes of the opposition parties (SPD, Greens, and Die Linke).[6] Opposition MPs criticized the law strongly, arguing that it was “an attack on parliamentary democracy” and would “fabricate majorities” (Volker Beck, Greens). The rhetorical style and arguments were precursors to the heated debate a dozen years later in 2023. The opposition challenged it again in the Constitutional Court. In 2012, the Court decided that surplus mandates may not exceed a certain total number (roughly fifteen), otherwise they had to be compensated or erased.

The Bundestag thus changed the electoral law by introducing compensatory mandates that were always added for the other parties if surplus mandates occurred. In this way, proportionality would be secured and the principle of equal vote guaranteed. But these compensatory mandates came at a price: they led to a strong growth of the Bundestag. In 2013, there were only four surplus mandates that led to twenty-nine compensatory mandates, four years later, forty-six surplus mandates produced sixty-five compensatory mandates, and, in 2021, thirty-four surplus mandates brought about 104 compensatory mandates.

The Bundestag of 2021 therefore had 736 members, making it the biggest national parliamentary chamber in the world. After Brexit, even the European Parliament was smaller than that. Worries abounded about the costs, effectiveness, and internal organization of parliamentary work in such a big parliament. Three Presidents of the Bundestag have tried to initiate reforms since 2013: Norbert Lammert (CDU), Wolfgang Schäuble (CDU), and Bärbel Bas (SPD). Over the years, academic experts have made many suggestions on how the electoral law could be fixed. The German Journal of Parliamentary Affairs (of which the author is an editor) alone has published over twenty articles with various suggestions for reform since 2013. [7]

An Advisory Commission of the Bundestag

The goal of this reform was to find cloture; the planned path was to gather a broad majority beyond the coalition-opposition divide. The president of the 19th Bundestag, Wolfgang Schäuble, had not been able to bring about a consensus among parties in a working group he had chaired himself. In his memoirs, he strongly criticized his party and the CSU for their lack of readiness to compromise, writing, “I failed in the reform of electoral law.”[8] Another attempt at a compromise was made through an expert advisory commission, a tool typically used by the government’s executive.[9] The 19th Bundestag installed it late in its term in April 2021. This commission included nine members of all parties in the Bundestag and nine academic experts, most of them constitutional scholars.[10] However, before the Bundestag election in September of the same year, the commission met only three times.

The coalition contract of the newly formed traffic light coalition stipulated in general terms that the electoral law would be reformed “within the first year.”[11] In March 2022, the new Parliament reinstalled an enlarged commission of twenty-six members.[12] It was tasked to make suggestions on a wide variety of topics, ranging from the representation of women and parity rules to the duration of the legislative term and the voting age. However, the commission could not form a broad consensus on the electoral law, and the commission submitted an intermediate report about the electoral system in the late summer of 2022. Based on a majority vote, it recommended that seats won by the first vote should only be distributed if there is coverage according to the second vote (Zweitstimmendeckung). The opposition members in the commission, including academic experts nominated by the opposition parties, objected to this in minority statements. The goal to find compromise through an expert commission was thus not achieved.

Pushing Through a Reform Bill by Simple Majority

Once the negotiations in the commission failed, hope to find a common model for the electoral system was diminishing. While according to media reports and statements of MPs in the plenary debate, consultations between the majority and the opposition parties continued, it was difficult to find a solution in a more politicized environment. Eventually, the coalition parties decided to push through a reform bill. The speed of it took many observers by surprise: The bill was formally introduced on January 15, 2023, and assigned to the committee of domestic affairs, which then held an expert hearing less than two weeks later. Some of the invited experts—ironically those that had been nominated by the CDU—argued that the included base mandate clause (Grundmandatsklausel) was an inconsistency in the law. According to this clause that had existed in the old electoral law, those parties that win at least three districts with the first vote do still participate in the proportional allocation of seats according to the second vote, even if they do not pass the 5 percent threshold. In the 2021 election. Die Linke had only gained proportional representation according to its 4.9 percent vote share because of this clause. Moreover, because the CSU is a separate party from the CDU, it, too, must pass the national threshold, even though it only runs in Bavaria. In the past, the CSU had always been above five percent nationally, but the 5.2 percent in 2021 were its worst-ever results, so there was some danger looming for it, too.

For the moment, the new rules have found a balance between different conflicting goals: proportionality, direct MP connection through electoral districts, the role of the state level, and protection of minorities.

When the bill came out of the committee phase and was reported back to the plenary, the base mandate clause had been eliminated. The implications were not instantly clear but soon gained attention, leading the CSU and Die Linke as well as the CDU to their massive critique of the electoral law. At the same time, the legal size of the Bundestag was set at 630 mandates, while the number of districts stayed at 299. The final readings in the Bundestag and the votes were taken on March 17, 2023. After the bill passed the Bundesrat in mid-May, it was promulgated by the Federal President and published on June 13, 2023.

The Bill in the Constitutional Court—and its Final Decision

On the very next day, the CSU and the State of Bavaria submitted their legal complaints to the Constitutional Court. The CDU and Die Linke later joined, as did a group of 4,000 citizens organized by the NGO “Mehr Demokratie” (More Democracy). Court proceedings and their timelines are always hard—if impossible—to predict. When the Court invited experts for testimony in late April 2024, it became clear that a decision might be taken before the summer.

This was indeed the case. On July 30, 2024, the Court presented its ruling (after it had inadvertently leaked the night before through a hidden link on the Court’s website). The decision was that the major change of the new electoral law was indeed not in conflict with the constitution: MPs only receive seats in a state if there are enough mandates according to the share of second votes (Zweistimmendeckung). However, the exclusion of small parties was deemed too strict, and the Court laid out various ways to secure their representation in a revised version of the law, for example, by lowering the 5 percent threshold or connecting various parties who do not compete (as CDU and CSU) for the vote share calculation. While leaving this final decision open, the Court mandated that the Grundmandatsklausel be immediately reinstated to secure representation until another solution has been found. While the Court decision is a success for the traffic light coalition, journalists argued that the reform bill had been “overturned in parts,”[13] leading to a competition for media framing by the parties where “there are only victors.”[14]

Shortly after the decision was made, MPs from the coalition and the opposition met. They decided not to start a new round of compromise-seeking and rather to keep the current electoral law—at least for the moment and the upcoming elections in 2025.

Consequences of the New Electoral Law

Questions about the likely effects of the new electoral law have been asked by its critics, for example: Will deserted districts exist without representation in the Bundestag? Simulations show that the number of MPs with a missing Zweitstimmendeckung is going to be very small. An analysis applying the new electoral law to voting behavior in 2021 came out at three cases.[15] The last-minute adjustment of the legal size of Parliament to 630 has further decreased this danger. Empirical research has shown that the representative behavior of MPs is not only driven by electoral rules but also by the candidate nomination process and incentives resulting from it.[16] Nomination in Germany—according to the electoral law—takes place by the respective party organizations in the district.[17] For MPs who compete for a place on the party list, it has become a de-facto prerequisite to get a district nomination first. Of the 736 MPs in the 20th Bundestag, 651 had been candidates in a district[18]—a share of 88.5 percent. Even if they were not technically elected there, they do uphold close ties there, conduct district work, and keep staff in district offices. Therefore, most districts actually have multiple MPs from different parties that claim to represent them even if they were not directly elected there. The danger of deserted districts is therefore overblown.

Another criticism refers to the balance between mandates filled by first and second vote. In the past, the legal size was 299 by district vote and another 299 by list vote. The new system has 299 by district vote and 331 by list vote. Yet if the surplus and compensation mandates are factored in, the current Bundestag has a share of 40.6 percent elected through first vote while according to the new law, the share will be 47.5 percent. Therefore, the importance of mandates earned by district vote is actually empirically strengthened. Nonetheless, empirical research shows that in real representative behavior there are no two types of MPs—those who are elected through the lists and those who won a direct mandate do not behave differently in a systematic fashion.[19]

The End of Electoral Law History in Germany?

Electoral reform has been a contested issue from the very beginning of the Federal Republic of Germany. Over the decades, numerous smaller and a few major changes to the electoral rules have been made by the Parliament and the Court. Does the decision in 2024 stand for the end of electoral reform history? Probably not. But for the moment, the new rules have found a balance between different conflicting goals: proportionality, direct MP connection through electoral districts, the role of the state level, and protection of minorities. In its current form, the electoral law continues to combine the best of the worlds of proportional representation and majority vote in single member districts.

But, while the result may be satisfactory to the Court and in line with the constitution, the reform process certainly is not. Discussion and strong political debate between the majority and the opposition is at the core of parliamentary democracy, there is also a need for compromise and getting things done together. This is particularly so with regard to the polity. Ernst Fraenkel and others have stressed a required basic consensus that refers both to overarching norms and rules of democratic procedure.[20] The electoral law should certainly be one of them.

At the same time, public attention to the topic of electoral reform has been much lower than among political actors and interested observers. Opinion surveys show that one argument, in particular, found strong support: limiting the size of Parliament.[21] In its decision, the Constitutional Court even referred to the public perception of the size of Parliament as a valid argument for reform. And this has been achieved.

The 21st Bundestag will most likely be elected based on the new law. It will show if and how the conflicts on electoral law remain prevalent or if some of the arguments and expectations made by political observers are overblown. In either case, the decision of the Constitutional Court did have a cooling effect for the moment—but the heat may go up again after the next election.

[1] I thank Daniel Hellmann for helpful comments; compare (in German) Daniel Hellmann, “Was taugt das neue Wahlgesetz?” Blickpunkt Nr. 13 (2024), Institute for Parliamentary Research.

[2] For a video of the plenary debate: Deutscher Bundestag, “Wahlrechtsreform zur Verkleinerung des Bundestages beschlossen,” March 17, 2023 (accessed August 11, 2024).

[3] Matthew Soberg Shugart and Martin P. Wattenberg, eds., Mixed-Member Electoral Systems. The Best of Both Worlds? (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001).

[4] Susan E. Scarrow, “Germany: The Mixed-Member System as a Political Compromise,” in Mixed-Member Electoral Systems. The Best of Both Worlds?, ed. Matthew Soberg Shugart and Martin P. Wattenberg (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), pp. 55–69.

[5] Richard Rose and Ian McAllister, Voters begin to choose. From closed-class to open elections in Britain (London: Sage, 1986).

[6] Deutscher Bundestag: “Parlament beschließt Änderung des Wahlrechts,” September 29, 2011 (accessed August 11, 2024).

[7] Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen, www.zparl.de (accessed August 11, 2024).

[8] Wolfgang Schäuble, Erinnerungen. Mein Leben in der Politik, (Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, 2024), p. 580, 583; translation from German by the author.

[9] Sven T. Siefken, Expertenkommissionen im politischen Prozess. Eine Bilanz zur rot-grünen Bundesregierung 1998-2005 (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag, 2007).

[10] Deutscher Bundestag, Kommission zur Reform des Bundeswahlrechts und zur Modernisierung der Parlamentsarbeit, (accessed August 11, 2024).

[11] “Mehr Fortschritt wagen. Bündnis für Freiheit, Gerechtigkeit und Nachhaltigkeit. Koalitionsvertrag zwischen SPD, Bündnis90/Die Grünen und FDP,” (2021) p. 13, translation from German by the author.

[12] Deutscher Bundestag, “Kommission zur Reform des Wahlrechts und zur Modernisierung der Parlamentsarbeit” (accessed August 11, 2024).

[13] Giggi Deppe, “Bundesverfassungsgericht hebt neues Wahlrecht in Teilen auf,” Tagesschau, July 30, 2024, (accessed August 11, 2024).

[14] Sophie Garbe, Dietmar Hipp, Timo Lehmann, Katherine Rydlink, and Jonas Schaible, “Wo ein Kläger, da nur Sieger,” Der Spiegel, August 2, 2024 (accessed August 11, 2024).

[15] Hellmann, “Was taugt das neue Wahlgesetz?” p. 10.

[16] Sven T. Siefken and Olivier Costa, “Available, Accessible and Ready to Listen,” in Political Representation in France and Germany. Attitudes and Activities of Citizens and MPs ed. Oscar W. Gabriel, Eric Kerrouche, and Suzanne S. Schüttemeyer (Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), pp. 87–115.

[17] See Suzanne S. Schüttemeyer, Pia Berkhoff, Malte Cordes, Oscar W. Gabriel, Daniel Hellmann, et al, Die Aufstellung der Kandidaten für den Deutschen Bundestag. Empirische Befunde zur personellen Qualität der parlamentarischen Demokratie (Baden-Baden: Nomos, 2024).

[18] Daniel Hellmann, based on the project “Candidates for Parliamentary Elections in multi-level Germany across Time” (CandiData), Institute for Parliamentary Research, Berlin (accessed August 12, 2024).

[19] Sven T. Siefken, “Observing the ‘Mandate Divide’ in Germany? The Roles of Direct and List MPs in the Bundestag,” paper prepared for the ECPR General Conference 2018 in Hamburg, Germany.

[20] Ernst Fraenkel, Deutschland und die westlichen Demokratien (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1991), p. 248.

[21] “Fast 80 Prozent der Menschen für Verkleinerung des Bundestages auf die Regelgröße ‚598‘,” Bertelsmann-Stiftung, Gütersloh, January 2023.