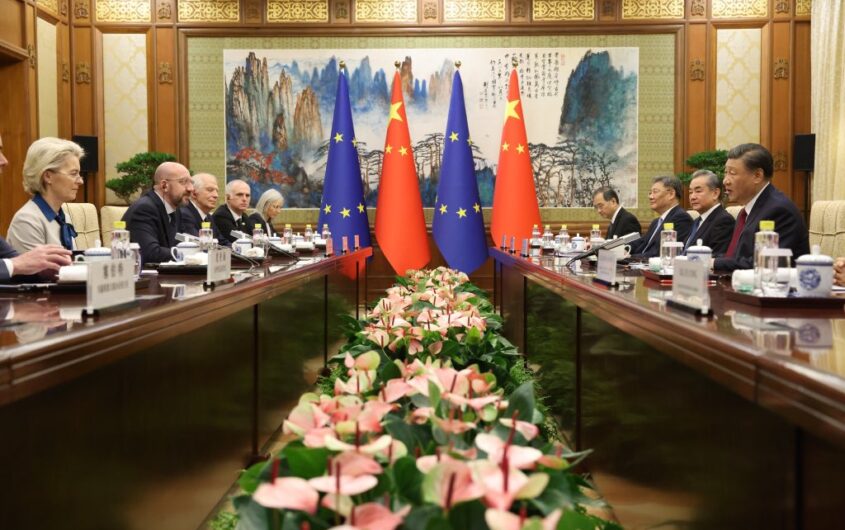

Josep Borrell via Twitter

China Is Listening

Yixiang Xu

China Fellow; Program Officer, Geoeconomics

Yixiang Xu is the China Fellow and Program Officer, Geoeconomics at AGI, leading the Institute’s work on U.S. and German relations with China. He has written extensively on Sino-EU and Sino-German relations, transatlantic cooperation on China policy, Sino-U.S. great power competition, China's Belt-and-Road Initiative and its implications for Germany and the U.S., Chinese engagement in Central and Eastern Europe, foreign investment screening, EU and U.S. strategies for global infrastructure investment, 5G supply chain and infrastructure security, and the future of Artificial Intelligence. His written contributions have been published by institutes including The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, The United States Institute of Peace, and The Asia Society's Center for U.S.-China Relations. He has spoken on China's role in transatlantic relations at various seminars and international conferences in China, Germany, and the U.S.

Mr. Xu received his MA in International Political Economy from The Josef Korbel School of International Studies at The University of Denver and his BA in Linguistics and Classics from The University of Pittsburgh. He is an alumnus of the Bucerius Summer School on Global Governance, the Global Bridges European-American Young Leaders Conference, and the Brussels Forum's Young Professionals Summit. Mr. Xu also studied in China, Germany, Israel, Italy, and the UK and speaks Mandarin Chinese, German, and Russian.

__

But It Won’t Be Business as Usual

When European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and President of the European Council Charles Michel departed China after last week’s EU-China Summit, they could congratulate themselves for having delivered their key concerns and demands without being rebuffed and lectured by their Chinese counterparts at every turn. Although there were no concrete deliverables, Beijing has committed to further discussions in technical groups to address the EU’s trade-related grievances and even complimented the bloc as a “pole” in its own right and not anyone’s vassal.

Compared with last year’s summit, which was subsequently dubbed a “dialogue of the deaf,” China’s notably more conciliatory gestures raised the prospect of containing escalating trade tensions between the two partners. But neither side walked away with any illusion of returning to a smooth relationship built on the ever-closer economic integration and geopolitical acquiescence of yesteryear. The China-EU relationship has been substantially transformed by different strategic outlooks and a much more competitive and, in part, aggressive global security environment.

Beijing’s more conciliatory attitude stems from its ongoing struggle to revive a sluggish economy dragged down by a nationwide real estate crisis, an export slump, and declining incoming foreign investment. A string of diplomatic assurances, including Xi’s recent siren call to American executives in San Francisco as well as policy incentives such as granting citizens from five EU countries visa-free travel to China, are intended to inject capital into and boost demand for China’s economy by bringing back, at least temporarily, elements of more closely integrated international financing and global supply chains.

Yet hopes for domestic market liberalization and other policy course reversals may be misplaced. Despite facing the serious threat of economic stagnation, Xi Jinping does not seem to be retreating from his determination to direct the course of China’s economy. After heavy-handed state interventions hobbled once high-growth elements of its private sector such as its big tech companies and tutoring industry, Xi continued to press for bigger roles for state-owned enterprises. Speaking at a recent meeting of the Central Commission for Comprehensively Deepening Reform, he called for these “natural monopolies” to be a priority destination for the investment of state capital. Xi has also pushed for tech self-reliance and accelerated domestic tech substitutions for government, military, and state-linked entities.

Even as Beijing assures the EU that it is willing to address the bloc’s 400 billion euro trade deficit with China, it is still committed to strengthening the country’s structural advantages in existing global supply chains. China’s massive funding of renewable energy is generating an oversupply of solar components in an industry that it continues to dominate. Chinese electric vehicle (EV) companies, faced with virtual exclusion from the United States and an anti-subsidy investigation from the EU, are keen to access these markets by manufacturing and assembling in countries such as Mexico, Thailand, and Serbia, all while Chinese EV battery producers are building capacities far beyond domestic demand.

The China-EU relationship has been substantially transformed by different strategic outlooks and a much more competitive and, in part, aggressive global security environment.

China’s economic support for Putin’s regime, another one of the EU’s major concerns, will also persist. Xi’s government regards Russia as a strategic partner for its foreign and security policy in a hostile international environment beset with “conflict and confrontation” from the West. Following unprecedented EU and U.S. sanctions, Beijing found new ways to exploit Russia’s growing economic reliance on China, buying generously discounted oil and gas, absorbing record amounts of Russian agricultural products, and conquering Russia’s consumer market with Chinese-made cars and phones. China also sought closer Sino-Russian collaboration on weapons development and Chinese participation in commercial and strategic exploitation in the Arctic. Von der Leyden and Michel’s request to rein in a list of Chinese companies suspected of circumventing the EU’s sanctions may be a face-saving way to encourage Xi to temper China’s economic support for Russia, but whether Beijing will take any meaningful action remains to be seen.

Aside from China’s strategic outlook, its rivalry with the United States will also play an important role in shaping its relationship with the EU. Washington has actively pursued cooperation with the EU to challenge China’s dominance in certain global supply chains and counter Beijing’s industrial policy and trade practices. Working through platforms including the. U.S.-EU Trade and Technology Council and G7 as well as with select EU member states, the United States seeks to implement effective export controls that would deny China access to the most advanced technologies. Emerging evidence of Western machinery and software in China’s military-industrial expansion, such as German-made five-axis machines used by the Chinese military to manufacture nuclear warheads, will add to the pressure to scrutinize the EU’s trade ties with China. Additionally, expanding U.S. efforts to exclude Chinese companies from its own technology supply chain buildup, most notably the Treasury Department’s Foreign Entity of Concern (FEOC) guidance that appeared in the U.S. Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), and the CHIPS and Science Act, incentivize European companies to reduce their supply chain exposure to China and even forgo competitive Chinese technologies in areas such as EV batteries.

The coming months will show to what extent Beijing is willing to accommodate Brussels’ demand for a more balanced bilateral trade relationship. It is even possible that new political rhetoric will develop in China that acknowledges growing competition with the EU while preserving vital economic ties. But it won’t be business as usual.