Kamerakinder via Wikimedia Commons

Germany Faces a Challenging Demographic Situation

Jörn Quitzau

Bergos AG

Joern Quitzau is a Geoeconomics Non-Resident Senior Fellow at AGI. He is Chief Economist at Bergos, a private bank based in Switzerland. He specializes in economic trend research and economic policy. Joern Quitzau hosts two Economics podcasts.

Prior to his position at Bergos, Joern Quitzau worked for Berenberg in Hamburg (2007-2024) and Deutsche Bank Research in Frankfurt (2000-2006) with a special focus on tax and fiscal policy.

Dr. Quitzau (PhD, University of Hamburg) was a Visiting Fellow at AGI in April 2014 and September 2022 and an American-German Situation Room Fellow in April 2018.

The German economy is weakening. This year, the gross domestic product (GDP) is expected to shrink by 0.5 percent. This puts Germany at the bottom of international growth rankings. By comparison, the U.S. economy will probably grow by around 2 percent this year. The Eurozone as a whole is expected to grow by 0.4 percent. The question is already making the rounds whether Germany is once again the “sick man of Europe.” It is still too early to make such a diagnosis. Certainly, Germany has some specific problems: for example, the Energiewende, which not only drives up energy prices but also deprives energy-intensive companies of planning security. Nevertheless, not everything is bad yet. Above all, the labor market gives hope. Employment has reached record levels. And in the current stagnating or recessionary economic environment, the big issue in Germany is not the threat of unemployment, but a widespread labor shortage.

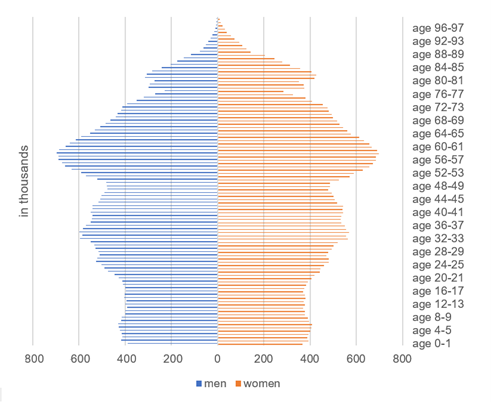

The labor shortage could become a serious structural problem for Germany. Because what has been predicted for decades is now becoming reality. The baby boomers (born between 1955 and 1969) are gradually leaving the labor market and retiring. In 2036, the last baby boomers will be retired. This means that the labor market will lose a very large number of qualified workers. And for the state, it means that very many previous taxpayers will become recipients of benefits (pensioners).

Age Structure Germany 2022

The resulting fiscal burdens can be quantified. The baby boomers have acquired extensive social security entitlements during their working lives that cannot be financed with the given taxes and contributions. The unfunded benefit claims can be understood as hidden or implicit public debt. Without countermeasures, these implicit debts would successively turn into explicit debts over the next years and decades. According to calculations by the Stiftung Marktwirtschaft and the Forschungszentrum Generationenverträge, the debt would rise to almost 450 percent of GDP. Even Germany would have difficulty finding lenders. Reforms are therefore inevitable. A longer working life is of central importance. The statutory retirement age of 67 would have to be successively raised further in order to relieve the social security system and increase the labor force potential. A longer working life with more flexible forms of employment for older people would also help to alleviate the labor shortage. Demographic change and the trend toward part-time work are reducing the volume of work and depressing the overall economic growth potential from around 1.5 percent so far to 0.5 percent in the medium term.

Even though hardly anyone likes to work longer, a look at the past shows where the problems of social security originate: In the 1950s, statistically speaking, people in Germany died shortly after retirement. Today, they still have considerably more than ten years ahead of them—and thus receive state pension as well as health and medical benefits. To exaggerate: back then, state pension insurance was an insurance against the possibility of living longer than one earned income through one’s own work. Today, on the other hand, state pension insurance is more or less a savings contract for old age.

Later retirement is not the only way to alleviate the labor shortage and relieve the social security system. Immigration can also cushion the problems. In fact, Germany has experienced remarkable immigration in recent years. The influx of refugees in 2015 as well as the strong immigration from Ukraine due to the war have drastically changed the demographic constellation in Germany. 2022 was the year with the highest immigration in the history of the Federal Republic. 2.67 million people came to Germany (1.1 million of them from Ukraine). In the same period, 1.2 million people left Germany, so that net immigration in 2022 was just under 1.5 million people. Compared to the previous record year of 2015, this was around 400,000 more people. Due to record immigration, Germany’s population grew by 1.3 percent to 84.4 million last year. Immigration thus also partly masks Germany’s economic weakness: the 1.9 percent GDP growth in 2022 is partly due to the fact that a good 1.1 million more people in Germany consumed and, in some cases, also worked.

The pure immigration figures suggest that Germany is well on its way to rejuvenating the population and solving its own demographic problem. However, whether people from Ukraine and other countries will stay when the wars in their home countries end is uncertain. In any case, Germany has not yet managed to control immigration in a way that primarily meets the needs of the labor market and public finances. So far, immigration has been strongly driven by geopolitical events. From a humanitarian perspective, Germany has done a great job in this regard in recent years. But when it comes to orienting immigration more towards its own needs, it is worth looking across the Atlantic. The United States and Canada have a long tradition of immigration and can provide valuable insights for Germany. The German government has discovered Canada in particular as a role model and has taken the first steps to draw inspiration from Canada for a modern immigration law. Good thing, because time is pressing.