Olga Ernst via Wikimedia Commons

Olaf Scholz’s New Cabinet

Isabelle Hertner

King’s College London

Isabelle Hertner is Senior Lecturer in Politics of Britain in Europe at King’s College London. She researches party politics in Germany, Britain, France, and at the European Union level. She is the director of King’s Centre for German Transnational Relations. Isabelle joined King’s in September 2016, having previously worked as a lecturer in German and European Politics and Society at the University of Birmingham. She was also the deputy director of Birmingham’s Institute for German Studies (IGS). Isabelle holds a PhD in European politics from Royal Holloway (University of London) and a MA in European Political and Administrative Studies from the College of Europe in Bruges. She did her undergraduate degree in Politics, French and Italian at the University of Erlangen-Nürnberg and spent a year studying at Sciences Po Bordeaux.

Something Old, Something New, Lots of Colors but no Blue

For some, Olaf Scholz’s new ‘traffic light’ coalition government is no more than a marriage of convenience. After all, the three parties that form this coalition—the Social Democrats (SPD, color red) and their two ‘junior’ partners, the Green Party (Bündnis 90/die Grünen, color green) and the Free Democrats (FDP, color yellow) differ too much in their worldviews. Still, after two months of intense negotiations, the parties first presented and then ratified the 177-page coalition agreement. On December 8, 2021, Olaf Scholz, a social democrat and former finance minister, took over the chancellorship from Angela Merkel. In his acceptance speech at the Chancellery, Scholz stressed that there is a great deal of consensus between Germany’s democratic parties and that this would continue to be one of Germany’s strengths. Scholz himself is often described as a consensus-maker, and this quality will be necessary for the management of his new government. In the following, I will describe Scholz’s new cabinet and discuss the allocation of ministerial posts. As we will see, there is ‘something old’ (experienced cabinet ministers), ‘something new’ (new cabinet ministers), ‘lots of colors’ (red, yellow, green), but nothing blue, in the sense that for the first time since 2005, the (blue) Conservatives aren’t part of the coalition. Blue is the color of the Christian Social Union in Bavaria, which forms a union with the Christian Democrats (CDU).

Who is who in Scholz’s cabinet?

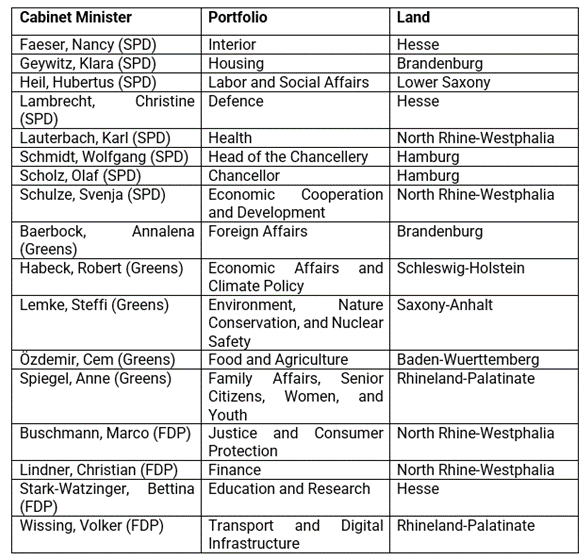

Scholz’s new cabinet is made up of sixteen ministers. Of these, seven belong to the SPD (plus of course, Scholz himself), five to the Greens, and four to the FDP. This allocation of posts strives to reflect the electoral results of the 2021 Bundestag elections: 25.7 percent for the SPD, 14.8 percent for the Greens, and 11.5 percent for the FDP. Table 1 (below) lists all members of the cabinet including their party affiliation, portfolio, and the Land (federal state) that their constituency is in.

Yet this cabinet seeks to represent more than just the percentages of votes. It also seeks to reflect the political priorities of the three parties, regional balance, a combination of experienced cabinet ministers and new faces, and gender and ethnic/religious diversity. I will now discuss each of these factors.

Issue ownership, expertise, and precedents

To a large extent, the allocation of ministerial posts reflects the three parties’ political priorities, or in political science jargon, their ‘issue ownership,’ which is the idea that voters consider specific parties to be better able to deal with some issues. For instance, the fact that the Social Democrats are in charge of the Labor and Social Affairs ministry is unsurprising, given their roots in the labor movement. Also, their 2021 manifesto focused largely on social justice. For example, they promised to increase the minimum wage to €12/hour. Furthermore, the SPD got the housing ministry at a time when there is a shortage of new, affordable, and social housing in Germany. Housing was framed as a matter of social justice.

Meanwhile, the Greens ‘own’ the issue of the environment, which includes climate change and nature conservation policies. We therefore should not be surprised that they are in charge of these two portfolios. Still, what stands out is the Green ‘super ministry’ for Economic Affairs and Climate Policy, which went to Robert Habeck, the vice-chancellor and Green Party co-leader. By bringing climate and the economy into the same ministry, Germany follows the examples of the UK and the Netherlands. It can be seen as an attempt to redefine the market and ‘green’ the German economy by making it more sustainable, e.g. through the introduction of more renewable energy. Finally, the Greens’ other co-leader, Annalena Baerbock, is Germany’s new foreign minister. Her appointment was no surprise as her campaign focused on international affairs, and in particular, democracy and human rights in Europe and beyond. She also follows in the footsteps of Joschka Fischer, the Greens’ first ever foreign minister (1998-2005).

Finally, the FDP got the finance ministry, which is one of the most influential and prestigious portfolios. The new finance minister, FDP leader Christian Lindner, is a free-market liberal who ensured that the coalition agreement was free of plans to increase taxes or take on more debt. How Germany’s green transition will be funded remains unclear, and we might expect some conflicts between Lindner and Habeck. The FDP also controls the Justice and Consumer Protection Ministry. In past coalition governments, the Ministry for Justice has often been taken by the FDP. The party owns the issue of civil liberties. Thus, each of the three parties got ministries matching their issue ownership. Whilst this feels like a win-win solution, the honeymoon period might be rather short-lived, given the conflicting goals of social justice and investment into the green economy on the one hand, and fiscal conservatism and low taxes on the other.

Regional imbalance

Furthermore, the allocation of posts reflects at least some regional balance. Germany being a federal state, and Germany’s political parties being federal institutions with powerful regional associations, the political representation of the Länder in central government matters. Scholz’s cabinet has a rather northern German note to it. Scholz is from Hamburg, as is his chief of staff (the head of the chancellery) Wolfgang Schmidt. Vice-Chancellor Robert Habeck is from Schleswig Holstein, while Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock and Labor Minister Hubertus Heil are originally from Lower Saxony. It means that several leading voices around the cabinet table ‘hail from the northern third of the country,’ according to Philip Oltermann. While there are three ministers from the southwestern Länder (Rhineland-Palatinate and Baden-Wuerttemberg), not a single Bavarian minister is to be seen. But then, Bavaria is a stronghold of the Conservatives, and they are now in opposition. This regional imbalance is of course at odds with the actual power dynamics inside Germany. After all, Germany’s economic powerhouse is the south, in Bavaria and Baden-Wuerttemberg. Whether this imbalance has any real political consequences remains to be seen.

Something old and something new

The new government is a mixture of experienced cabinet ministers from the federal and regional governments, but also, Members of the Bundestag and Landtage (regional parliaments). For a start, Olaf Scholz, Christine Lambrecht, Svenja Schulze, and Hubertus Heil were members of Angela Merkel’s last government. Several others were ministers at the regional level, such as Robert Habeck, who was minister for energy, environment, and agriculture of his home state Schleswig-Holstein between 2012 and 2018. Meanwhile, Christian Lindner and Annalena Baerbock were MPs and party leaders before joining Scholz’s cabinet. An interesting appointment is that of Nancy Faeser, who was the SPD’s spokesperson for the interior in the state of Hesse. Faeser did much to advance the investigation into right-wing extremist crimes. By appointing her as Interior Minister, Scholz has demonstrated the willingness to face the rising numbers of right-wing extremist crimes.

Overall, this combination of ‘old and new’ ministers can be advantageous, as not everyone needs to learn the rules from scratch. Due to COVID-19 and other urgent issues, new ministers won’t have much time to learn the ropes.

‘Daring more progress’ (Mehr Fortschritt wagen)? Gender balance and ethnic minority representation

Olaf Scholz’s cabinet is gender balanced—if one doesn’t count Scholz. When he announced his choices for the interior and defense portfolios (Nancy Faeser and Christine Lambrecht), Scholz said Germany’s ‘security will be in the hands of strong women.’ I would add that at the international level, Germany will also be represented by a strong woman (for the first time): Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock. Perhaps an even more radical step would have been the appointment of a female finance minister and a male minister for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women, and Youth. Perhaps in 2025.

Importantly, of all seventeen cabinet members, only one has an ethnic minority background. Cem Özdemir, the new minister for food and agriculture, has Turkish ancestry. He was one out of the two first MPs of Turkish ancestry when he first entered the Bundestag in 1994, and he is the first-ever cabinet minister with a ‘migration background.’ Whilst his appointment is important in terms of the symbolic representation of ethnic minorities, more needs to be done to enhance ethnic diversity at the highest level of government. After all, the new Bundestag is more ethnically diverse than ever before, as at least 11.3 percent of MPs have a migration background (up from 8.2 percent). Some will rise through the ranks of their parties and become ministers. For now, a gender-balanced cabinet is a major achievement. A more ethnically balanced government would be the next logical step.