The Political and Electoral System of Germany

Eric Langenbacher

Senior Fellow; Director, Society, Culture & Politics Program

Dr. Eric Langenbacher is a Senior Fellow and Director of the Society, Culture & Politics Program at AICGS.

Dr. Langenbacher studied in Canada before completing his PhD in Georgetown University’s Government Department in 2002. His research interests include collective memory, political culture, and electoral politics in Germany and Europe. Recent publications include the edited volumes Twilight of the Merkel Era: Power and Politics in Germany after the 2017 Bundestag Election (2019), The Merkel Republic: The 2013 Bundestag Election and its Consequences (2015), Dynamics of Memory and Identity in Contemporary Europe (co-edited with Ruth Wittlinger and Bill Niven, 2013), Power and the Past: Collective Memory and International Relations (co-edited with Yossi Shain, 2010), and From the Bonn to the Berlin Republic: Germany at the Twentieth Anniversary of Unification (co-edited with Jeffrey J. Anderson, 2010). With David Conradt, he is also the author of The German Polity, 10th and 11th edition (2013, 2017).

Dr. Langenbacher remains affiliated with Georgetown University as Teaching Professor and Director of the Honors Program in the Department of Government. He has also taught at George Washington University, Washington College, The University of Navarre, and the Universidad Nacional de General San Martin in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and has given talks across the world. He was selected Faculty Member of the Year by the School of Foreign Service in 2009 and was awarded a Fulbright grant in 1999-2000 and the Hopper Memorial Fellowship at Georgetown in 2000-2001. Since 2005, he has also been Managing Editor of German Politics and Society, which is housed in Georgetown’s BMW Center for German and European Studies. Dr. Langenbacher has also planned and run dozens of short programs for groups from abroad, as well as for the U.S. Departments of State and Defense on a variety of topics pertaining to American and comparative politics, business, culture, and public policy.

__

The Federal Republic of Germany is a constitutional republic with the Federal President (Bundespräsident/in) as the Head of State with limited political power. The incumbent is Frank-Walter Steinmeier (formerly a powerful SPD politician). The next election is in February 2022. Steinmeier has indicated that he wants to stand for a second term and has good chances for reelection.

The head of government is the Chancellor (Bundeskanzler/in) who needs to gain majority support in or retain the confidence of the all-powerful lower house of parliament, the Bundestag. This person (almost) always leads the largest party. There have only been CDU and SPD chancellors since the Federal Republic was established in 1949.

There is an upper house of parliament, the Bundesrat, that consists of 69 members representing the federal states. Each state gets between 3 and 6 votes—the smaller states have disproportional power. However, there are no permanent members; rather, a number of votes directed by the disparate coalition governments in power at the state level. The Bundesrat does not exercise too much legislative power (mainly delaying, some amending) and the policy areas over which it can weigh in were reduced by the federalism reforms over the last fifteen years.

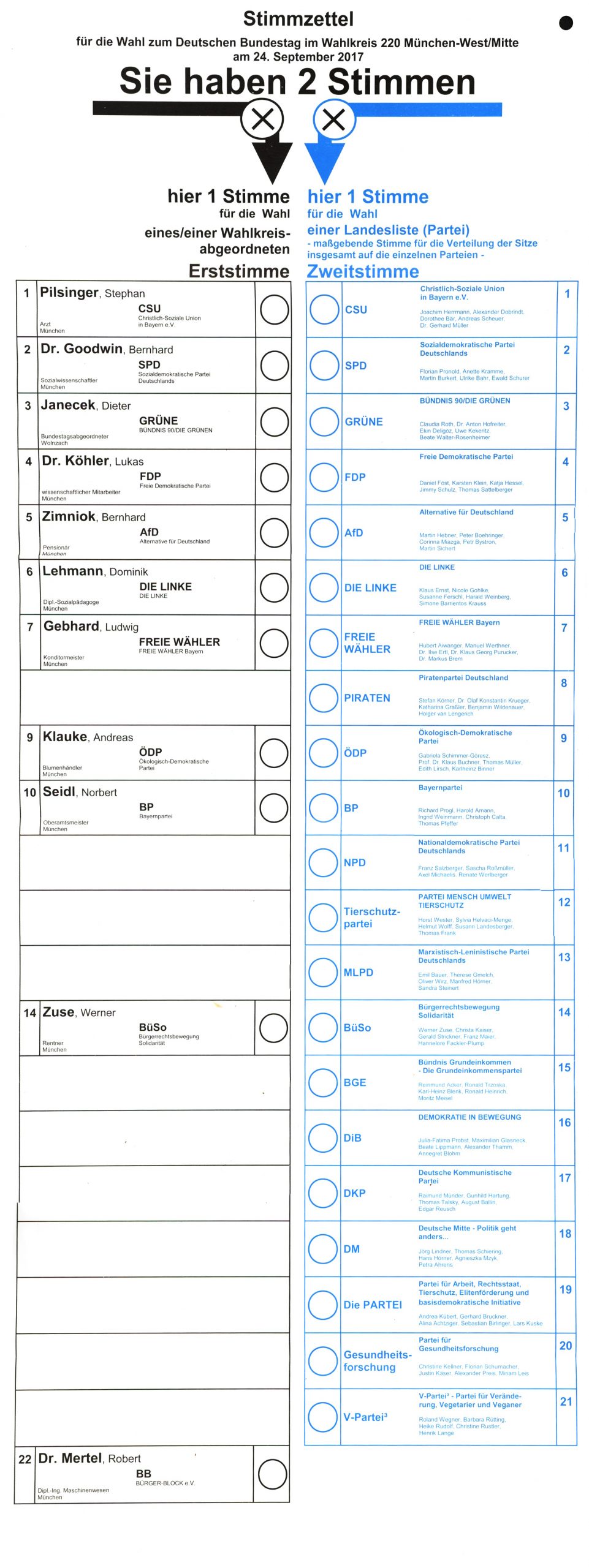

In the Bundestag, the electoral system is a mixed-member proportional or personalized proportional system.

- Of the minimum 598 seats, half (299) are small, territorially compact constituencies that elect a single member who has garnered the most votes—single member plurality. This is called a Direktmandat. Each state gets a number of constituencies corresponding to its share of the country’s total population. Voters get a separate vote (Erststimme) for this representative. Non-partisan commissions must follow detailed instructions regarding population size and respect for pre-existing jurisdictions when boundaries are changed—gerrymandering is not a problem.

- The other half of the seats are allocated using proportional representation (PR)—the Sainte-Laguë/Schepers method based on voters’ second vote preferences (Zweitstimme). This is a closed-list PR system in which the state-level parties determine the names on the list and the rank orders. Order matters because if a party were to get, for example, 10 representatives from the list in a certain state, the top 10 names would then join the caucus in Berlin. Allocation is done at the state level but based on national vote totals. Each state gets exactly the same number of PR seats as constituencies—e.g., North Rhine Westphalia has 64 constituencies and 64 PR seats=128 seats. Importantly, constituencies already won by a party with the first vote are subtracted from their perfect theoretical PR total.

There are several caveats:

- Parties must get 5 percent of the national vote to be eligible for their PR allocation but keep whatever constituencies they won with the first vote.

- If a party wins 3 or more constituency seats, they receive seats corresponding to their national vote total (even if that is under 5 percent).

- Sometimes parties win more first vote seats in a state than they should receive in a perfectly proportional allocation based on the second vote totals. If this happens, the party keeps the seats and the size of the Bundestag is increased accordingly. These are called overhanging mandates (Überhangmandate). There have always been overhanging mandates, but these have increased over time as the party system has become more complex. Essentially, there is more divergence between first and second vote choices, producing more of these mandates.

- Due to a Constitutional Court decision, since the 2013 election, there are also so-called compensatory mandates (Ausgleichmandate)—to ensure the best vote-seat correspondence, benefitting smaller parties, as well as to avoid the so-called negative vote weight (negatives Stimmgewicht). The current Bundestag (2017-2021) is the largest ever with 709 seats, including 111 overhanging and compensatory mandates. The parliament is now larger than the European Parliament and the extra members have cost taxpayers millions. Unsurprisingly, there is once again pressure to revise the electoral laws, but nothing will happen until the next legislative period.

In light of the overwhelming use of proportional representation, there is a very close vote/seat correspondence and a multiparty system—moderate, although now verging on extreme multiparty. There are currently six formal parliamentary factions and seven parties (Bavaria’s CSU is formally independent, but always caucuses with the CDU in the Bundestag).

There have always been coalition governments since 1949 with the possible exception of 1957-1961 (see below).

The Parties’ Colors

CDU/CSU (Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union)—Black—traditionally associated with political Catholicism because of priests’ clothing and the center-right more generally.

SPD (Social Democratic Party of Germany)—Red—the color of emancipation at least since the French Revolution has been associated with leftist parties for 200 years.

Greens (Alliance 90/The Greens)—Green—pretty straightforward.

FDP (Free Democratic Party)—Yellow—more contested, given the association of the color with treason but linked to (classical) liberalism since the 19th century.

AfD (Alternative for Germany)—Blue—this is a very recent and weak convention for this right-populist or right-radical party—the CSU is often portrayed in lighter, Bavarian blue. Note that brown is the color of fascism or the radical right.

Left Party (die Linke)—Purple or Pink—red is already taken, even though this is a more radical leftist party. This is the weakest color relation.

Coalition Types

Germans love naming various coalition options—often based on the parties’ colors and sometimes because of the resemblance to the colors of various flags.

CDU/CSU-SPD—grand coalition

CDU/CSU-FDP—bourgeois coalition

CDU/CSU-SPD-FDP—“Germany”/Black-Red-Yellow coalition

SPD-FDP—social liberal coalition

SPD-FDP-Greens—traffic light coalition

CDU/CSU-Green—Black-Green coalition

CDU/CSU-FDP-Green—Jamaica coalition

CDU/CSU-SPD-Green—Kenya or Afghanistan coalition

SPD-Left—Red-Red coalition

SPD-Left-Green—red-red-green coalition

Chancellors and Coalitions of the Federal Republic

Konrad Adenauer 1949-1963—bourgeois (CDU/CSU-FDP except for 1957-1961)*

Ludwig Erhard 1963-1966—bourgeois (CDU/CSU-FDP)

Kurt Georg Kiesinger 1966-1969—grand (CDU/CSU-SPD)

Willy Brandt 1969-1974—social liberal SPD-FDP)

Helmut Schmidt 1974-1982—social liberal (SPD-FDP)

Helmut Kohl 1982-1998—bourgeois (CDU/CSU-FDP)

Gerhard Schröder 1998-2005—red-green (SPD-Greens)

Angela Merkel 2005-2021—grand, bourgeois, grand (CDU/CSU-SPD, CDU/CSU-FDP, CDU/CSU-SPD)

*Adenauer’s governments also included two other small conservative parties, the German Party (DP) and the All-German Bloc/League of Expellees and Deprived of Rights (GB/BHE), representing Germans mainly from the former eastern territories—both of which ceased to exist by 1961. Technically, Adenauer’s third government was a coalition of CDU/CSU and the DP—but it is often referred to as a single party majority government because the CDU/CSU gained more than 50% of the votes and seats, yet included the DP anyway. This was the only such victory since 1949, although Merkel came very close in 2013.

Current Polling

The typical question is called the Sonntagsfrage (elections are always on a Sunday)—“If the Bundestag election were held on Sunday, which party would you vote for?”

Wahlrecht | Infratest | Der Spiegel