onnola via Flickr

Integration Interrupted?

Susanne Dieper

Director of Programs and Grants

Susanne Dieper is the Director of Programs and Grants at AICGS. She oversees the Institute’s programs and projects within the three AICGS program areas, manages all AICGS fellowships, and is in charge of grant writing. Her current focus is on issues related to transatlantic relations, immigration and integration, diversity, the next generation of leaders, workforce education, and reconciliation. She develops programs that align with the mission of AICGS to better understand the challenges and choices facing Germany and the United States in a broader global arena.

Previously, Ms. Dieper was in charge of organizational and project management at AICGS as well as human resource development and board of trustees relations. Prior to joining AICGS, she worked in transatlantic exchange programs, language acquisition, as well as the insurance industry in Germany.

Ms. Dieper holds an MBA from Johns Hopkins University with a concentration in International Business and an MA in English Linguistics and Literature, History, and Spanish from the University of Cologne. She has completed course work in nonprofit management at Johns Hopkins University.

__

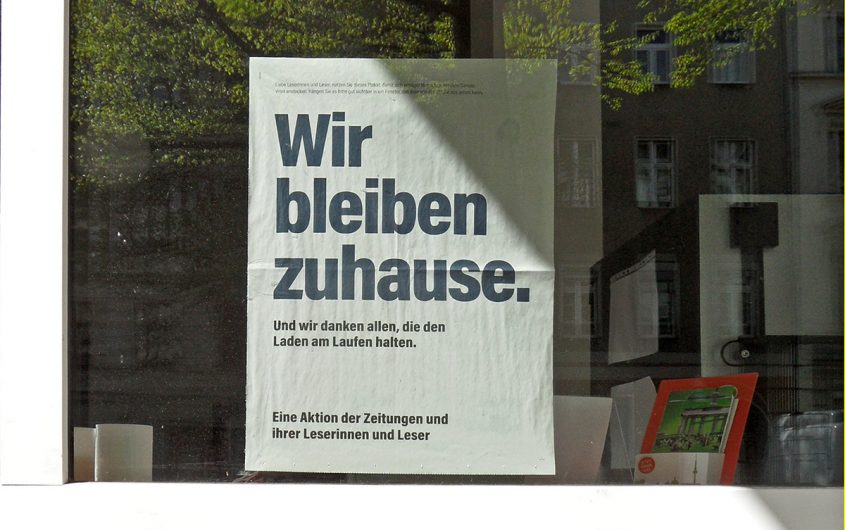

Some Effects of COVID-19 in Germany

During the Coronavirus pandemic, the issues surrounding refugees, immigration, and integration have largely receded into the background in both Germany and the United States. While they had been prioritized in both countries previously, especially in 2015 as the refugee situation began in Europe and then-presidential candidate Donald Trump intensified his anti-immigrant rhetoric, COVID-19 has eclipsed migration issues in the public discourse. Immigration hardly even featured during the final months of the U.S. presidential election in 2020. Voters and officials have predominantly been concerned with the health crisis and the economic fallout of the pandemic.

Some positive developments have emerged for migrants and refugees in both countries. The new Biden administration has announced changes to U.S. immigration policies and reversals of the most stringent approaches implemented under his predecessor. These include an increase in the number of refugees allowed in the country, changes to the removal procedures of undocumented migrants, and the preservation and fortification of DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals). In Germany, the general public appears less concerned with refugee and integration questions as well. On February 26, 2021, only 6 percent of those surveyed indicated a concern over the topic of foreigners/integration/refugees, down from a peak of 61 percent in late June 2018. Even the far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) has changed its tune and now purports to view all those as lawful German citizens (and potential voters) who possess a German passport, even those with a migration history.

One might think that, after taking in over a million refugees in the past several years, German society has moved on to integration and acceptance. The German government tasked a Fachkommission zu den Rahmenbedingungen der Integrationsfähigkeit (Expert Commission on Framework Conditions of Integration Capabilities) with exploring an array of issues in the areas of migration and integration between February 2019 and January 2021. The committee has recently published its findings and recommendations to improve the country as an immigration society. One of its many recommendations is a change in how to identify immigrants and their families: from “people with a migration background” (a term that has long been controversial) to “immigrants and their descendants.” The change would classify those born to immigrants in Germany simply as Germans and no longer label them as having a migration history. This recommendation has been widely lauded and would indicate a positive step toward social cohesion.

But reality shows a more nuanced and less positive picture for migrants and immigrants in Germany as a result of the pandemic. Similar to the situation in the United States, where minorities have suffered the most severe consequences of the health and economic fallout of the pandemic, migrants, refugees, and recent immigrants in Germany have fared worse compared to the rest of society. Integration in many areas has been halted or impeded. Employment data show that refugees and migrants have suffered job loss at a higher rate during the pandemic compared to the rest of society. According to the German Employment Agency, the unemployment rate for migrants from non-EU countries rose by 17 percent in January 2021. Underemployment is also higher for these migrants compared to the general population.

The inability to work also has had a negative impact on the social integration of migrants and refugees.

Refugees, migrants, and non-migrant women work in industries that the International Labor Organization (ILO) has classified as being impacted by the pandemic to a high degree. These industries include auto-repair, manufacturing, accommodation, and food services. As a report by the ifo Institute Munich outlines, social distancing and the possibility of working remotely are almost impossible in these industries, and the risk of exposure to COVID-19 is particularly high. In 2018, over 50 percent of migrants were working in these industries. Many migrants, in particular recent arrivals, also do not qualify for government support in the form of Kurzarbeit (shortened work), due to their special employment status and restricted work permit. As a long-term effect of the pandemic, migrants will therefore suffer significant economic distress and their perspectives for a decent way of living in Germany will likely also diminish. In addition, the socioeconomic divide between affected groups and those who do not have a migrant background is expected to widen in the future.

Before the pandemic, the employment numbers for refugees who found work had been steadily progressing: five years after arrival, 55 percent of refugees were employed. Those who had brought skills fared even better and were able to contribute to the severe skilled-labor shortage in Germany. This positive development has halted. Many refugees are unable to find work in the same way as before the pandemic, given the lockdown restrictions and their employment status. The inability to work also has had a negative impact on the social integration of migrants and refugees. The pandemic has slowed German language acquisition (which took place almost exclusively in the classroom), networks, and contacts needed to find training and job opportunities are no longer available to the same degree, and the crucial personal connection to and interaction with other people has largely been lost. Laudably, in October 2020 Germany’s integration minister Annette Widmann-Mauz announced a “digital offensive” to continue integration and language classes for immigrants. However, access to the Internet or a computer has been a challenge for many who live in less affluent communities or in a refugee center. While motivation to pursue educational advancement and find work has generally been high among refugees, the pandemic will undoubtedly put a damper on those trends as well. Living and working during a pandemic has impacted the physical and mental health of many, even those with a steady income.

Germany will benefit from continuing and enhancing its integration and education efforts on behalf of migrants and refugees

Despite earnest efforts by integration professionals, many refugees feel forgotten. Several refugee centers have experienced COVID-19 outbreaks and the resulting quarantine restrictions have halted their occupants’ lives. Memet Kiliz, who heads the German Council on Immigration and Integration, says that recent refugees are affected the most, as they not only fear for their health but also their prospect of being granted asylum in Germany. Nevertheless, a somewhat positive trend in Germany can be observed: the most recent Integrationsbarometer (a study that assesses the integration climate in Germany) of the Sachverständigenrat deutscher Stiftungen für Integration und Migration (SVR) (Expert Council on Integration and Migration) shows that societal cohesion has expanded in Germany during the pandemic and that people with a migrant background have developed an increased trust in democracy and politics. Trust and satisfaction with politics have also improved, despite or because of the policies and restrictions implemented by the government to counter the pandemic. Hopefully, this trend will continue post-Coronavirus.

Germany has largely come to terms with the fact that it is an immigration country, increasingly displaying an open mind and welcoming mentality towards others. It also needs more workers, especially high-skilled, to sustain the country’s future. The country will benefit from continuing and enhancing its integration and education efforts on behalf of migrants and refugees, and it must strive to reverse the negative outcomes of the pandemic suffered by the most vulnerable.