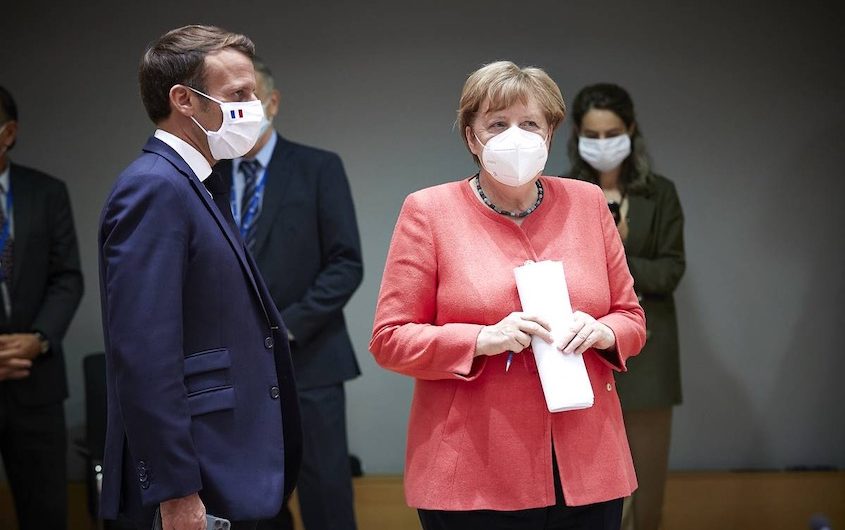

European Union via European Council Newsroom

EU Special Summit Agrees on Post-Pandemic Recovery Fund

Jörn Quitzau

Bergos AG

Joern Quitzau is a Geoeconomics Non-Resident Senior Fellow at AGI. He is Chief Economist at Bergos, a private bank based in Switzerland. He specializes in economic trend research and economic policy. Joern Quitzau hosts two Economics podcasts.

Prior to his position at Bergos, Joern Quitzau worked for Berenberg in Hamburg (2007-2024) and Deutsche Bank Research in Frankfurt (2000-2006) with a special focus on tax and fiscal policy.

Dr. Quitzau (PhD, University of Hamburg) was a Visiting Fellow at AGI in April 2014 and September 2022 and an American-German Situation Room Fellow in April 2018.

After four days of intensive negotiations, the EU special summit has finally made a breakthrough: EU leaders agreed on a recovery fund to combat the economic consequences of the coronavirus pandemic. The total volume of €750 billion is in line with the EU Commission’s concept that made the headlines in May. The total amount is made up of €390 billion in non-repayable grants and €360 billion in repayable loans. The EU Commission’s proposal had envisaged a higher share of grants (€500 billion). Austria, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, and the Netherlands have pushed through a higher share of loans. Bottom line, Europe has sent a strong signal of solidarity in times of the corona crisis.

The Recovery Fund has made headlines not only because of its volume. Two details are almost even more important: first, the money will be raised via the capital market. The European Union will thus become a player on the bond market. This is remarkable because, until now, loan financing was considered impossible under Articles 310 and 311 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. Second, the reconstruction fund brings with it an unusually high degree of redistribution. The loans will be repaid from the future EU budgets up to 2058.

What has been somewhat missed in the reporting: the new fund will not be able to alleviate the acute economic slump, because the funds will not flow significantly until 2021. The bulk of the money will probably flow in 2021 until 2024, i.e., at a time when the economy should have long recovered. Nor will it necessarily help the particularly affected sectors in the particularly affected countries get back on their feet. This is evident, for example, in the tourism industry in Spain, Italy, and Greece: the reason for the current problems in tourism is not a lack of money among potential tourists. Any economic program cannot remedy the real reason: the infection risk associated with the mass tourism. Obviously, the EU Commission’s proposal also aims in another direction. It explicitly states at one point that the pre-crisis situation should not be restored. Instead, the funds are to be channeled into the “European Green Deal as the EU’s construction strategy,” into “strengthening the internal market and adapting it to the digital age” and into “a fair and inclusive development for all.” The outcome of the EU special summit has confirmed this: 30 percent of the total expenditure from the multiannual financial framework and the recovery fund will target climate-related projects.

It is not so much an instrument of economic policy to bridge or shorten a temporary period of weakness. It is more of an industrial policy or European policy vehicle.

The term recovery fund is thus somewhat misleading. It is not so much an instrument of economic policy to bridge or shorten a temporary period of weakness. It is more of an industrial policy or European policy vehicle. It is also intended as a sign of European solidarity toward the countries particularly affected by the pandemic.

Is that a big surprise? At first glance it is, because Chancellor Angela Merkel has suddenly given up the traditional German resistance to common debts and to an expansion of intra-European transfers. However, if you look at the history of the monetary union, the move should not come as a particular surprise.

Before the start of the European Monetary Union, there was sometimes bitter controversy among economists and in the political arena about the right time to introduce the euro. At that time, the controversies revolved around the so-called coronation theory on the one hand and the locomotive theory on the other. The coronation theory simply states that the countries of Europe must first come closer together economically and politically, and only at the end of this process can the common currency be introduced — as a kind of coronation. The countries then resemble each other so much that the monetary union can function without tension right from the start. The majority of economists held this view back then. The locomotive theory, on the other hand, says that a common currency would further promote European integration and that it would result in an ever-closer economic and financial policy union. The early monetary union would thus become the engine of integration, even if it did not function smoothly from the outset.

The rest is history: against the majority advice of the economists, the euro started in 1999. In this respect, the euro has been a political project from the outset that does not primarily function according to economic laws. For this reason, some economists have burned their fingers in recent years with the prediction that the euro will soon break up. They have argued based on economic theory and overlooked the fact that politicians will do everything possible to ensure that the euro project does not fail. This is only logical, because the locomotive theory is based precisely on the fact that the constraints caused by the euro make political steps possible that would not have been possible without the euro or only much later. It is obvious that such steps are mainly taken in times of crisis. In this respect, we are contemporary witnesses of how the locomotive theory is being brought to life.

In the end, everything boils down to a European fiscal union. The exciting question is: will it be a highly competitive growth union or rather a low-growth transfer union? We can only hope that the locomotive will find its way toward a growth union in the medium and long term and that the monetary union will not have to be held together permanently by transfers.