World Bank / Henitsoa Rafalia via Flickr

Germany’s Role in Global Health

Ilona Kickbusch

Global Health Centre, The Graduate Institute Geneva

Professor Ilona Kickbusch PhD is known throughout the world for her expertise and is a sought after senior adviser and key note speaker. She has a strong commitment to the empowerment of women.

She is the founding director and chair of the Global Health Centre at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva.

She has had a distinguished career with the World Health Organization and Yale University.

The Lancet has profiled her as a global health reformer.

She has been awarded the Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (Bundesverdienstkreuz) in recognition of her invaluable contributions to innovation in governance for global health and global health diplomacy.

She works as an independent global health consultant based in Brienz, Switzerland

The focus for German Global Health activities presently is threefold:

- as a strong supporter of multilateral responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in a wide range of UN and other political bodies,

- taking WHO reform proposals forward as a member of the Executive Board of the WHO (2018-2021), and

- using the upcoming EU presidency starting July 1, 2020, to strengthen the EU role in global health.

1. An opening political space on global health governance supports new leadership.

The Spring of 2020 saw a peak in political attention to global health governance and drew attention to the fragility of international cooperation. As the U.S. announced its intention to defund the WHO and accused the organization of acting at the behest of China, there followed a disarray in global health diplomacy. The U.S. position has been reinforced by the letter to WHO by President Trump on May 19, 2020. This drastic measure by the U.S. despite weeks of negotiation has underlined the Trump administration’s disdain for multilateral approaches. But as always, new political spaces emerge, and new actors get ready to step into the gap. It has been the hope of many that the EU and its member states will be willing to occupy the political space that is emerging—an opportunity for its soft power expansion in a multipolar world. There are first signs of this in global health—but as an exercise in partnership with the global south, Africa in particular. At the end of November 2019, the European Parliament approved the new European Commission headed by Ursula von der Leyen; she has been clear that it aims to be a “geopolitical commission.” As one dimension of this it has already reached out to African countries for stronger cooperation. The EU, after all, is the largest development funder contributing about €75 billion in 2018.

2 .“Who, if not us?” After a period of disorientation, the geo-political response by small and middle power countries has begun to be proactive to fill the void.

The Alliance for Multilateralism, a loose group of nations and other actors working to boost international cooperation was established; it was launched with France on April 2, 2019. A recent virtual meeting of the group brought together foreign ministers from almost 30 countries—all small and middle powers—to initiate a collective answer to the COVID-19 pandemic. Their joint declaration sent a strong signal of support to the United Nations, including the World Health Organization as the backbone of the global response to COVID-19. The Alliance will seek to ensure sufficient financing to address the COVID-19 crisis, including funds aimed at strengthening health systems globally, and just distribution and universal access to treatment and vaccines, when they are ready. Immunization against COVID-19 should be recognized as a global public good. These messages were reflected in many of the statements of the members of this group at the World Health Assembly (WHA73) on May 18/19, 2020 and at the EU pledging event on May 4, 2020.

3. Two large trends in multilateralism impact on Germany’s global health role.

The U.S. has withdrawn from several international agreements and agencies and is now threatening to leave WHO. It has deeply upset many of its traditional allies in the process. China, on the other hand, has systematically been active in the multilateral system with a longer-term strategy of changing rules. This was also obvious at the virtual WHA73 on May 18, 2020, where the Chinese president Xi Jinping spoke in support of multilateral processes—whereas the U.S. launched a scathing attack on China and the WHO. The small and middle powers had worked hard to find a consensus (122 initially agreed to co-sponsor a resolution, including all BRICS countries minus China). This show of unity indicates their awareness that it is they who “have the most to lose from a transition away from an open and consensual order to a world where ‘might makes right’ at the expense of international norms, rules and institutions.”

4. Germany is a key middle power with a strong interest in a rule based, rather than a power based, global order.

Its economic growth based on exports is heavily dependent on reliable global flows and rules that bind, also within the EU. But Germany’s commitment to multilateralism goes deeper than economic interest for historical reasons and is therefore perhaps different from some other European players—particularly those that look back on a more extensive colonial past such as the UK and France.

5. All German foreign policy engagement—including global health—can only be fully understood in the context of its own history.

In global health this explains the commitment to human rights, multilateralism, health as a social contract defined by solidarity (the Bismarck model of social protection), and a link between development and investment, based on Germany’s own development trajectory after World War II. The President of Germany, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, reiterated this position, saying “Our historical experience has destroyed any belief in national exceptionalism—for any nation.” Therefore, any claim for a “global” political leadership role is rapidly challenged both from within and outside of Germany.

6. The increased German activity in global health must therefore always be seen in the context of a change in perspective in German foreign policy, which is testing out different multilateral approaches to take more global responsibility.

Soft power and multilateralism (rules-based order and legitimacy) are the starting point and guide for Chancellor Merkel’s strong interest in global health. The strategy to use existing international bodies such as the UN, WHO, and G7 and G20 to gain influence and position global health was established early on. As Merkel has remained in power since 2005, she has also provided exceptional continuity for Germany’s global health commitments at the highest political level. Germany moved to become a member of the WHO Executive Board from 2009-2012 to push WHO reforms. The visibility for global health during the G8 presidency led to a higher global health awareness within Germany and to the initiative to establish the World Health Summit in Berlin, which was to become an ever more important annual global health meeting. A detailed overview of these developments is provided in a 2017 Lancet Paper on Germany’s expanding role in Global Health.

7. Based on this commitment to global health and multilateralism, Germany over the years has significantly increased its political support and funding to the World Health Organization.

It remained supportive to the WHO when it was attacked over its belated response to the Ebola outbreak in West Africa and gave a major signal on May 18, 2015, when Chancellor Merkel gave an opening speech at the 68th World Health Assembly in Geneva. She stated: “WHO is the only international organization that enjoys universal political legitimacy on global health matters.” She reiterated this point of “legitimacy” in her address to the WHA73 on May 18, 2020. Germany has been an exceptionally reliable partner of the WHO—and Germany has at recent G7 and G20 meetings in 2020 also taken a clear position in support of the WHO in the face of U.S. attacks on the organization. But Germany has also supported other health organizations; for example, under the auspices of Germany’s G7 presidency in 2015, the Gavi replenishment was an opportunity for global leaders to stand together and mobilize an additional $ 7.5 billion for vaccination.

8. Under the leadership of Health Minister Gröhe (2013 to 2018) in the third Merkel government, the Ministry of Health received its own flexible budget for global health which allowed it to help WHO directly through financial support (i.e., for the emergency contingency fund).

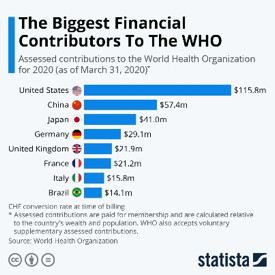

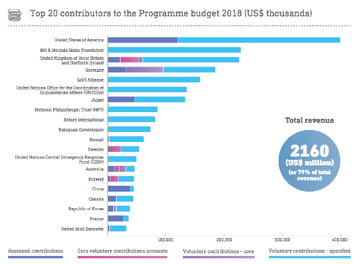

The WHO website states that the German Federal Ministry of Health has committed €115 million in voluntary funds to WHO for a four-year period. These predictable funds will help WHO and partners implement programs to achieve SDG 3 and WHO’s 5-year strategic plan (GPW13, 2019-2023). This builds on a prior total German contribution of $190 million for the period of 2016-2017. Germany presently is the fourth largest contributor to WHO in terms of assessed contributions. It had proposed a 10 percent increase in assessed contribution for all countries in 2017, but countries only agreed to 3 percent. It has also announced additional funding ($176 million) to the WHO health emergencies program at the virtual WHA73.

9. Germany defines itself as a “critical friend” seeking to find better ways for the functioning of the multilateral system and WHO—also in relation to COVID-19.

In keeping with this concern—with Norway and Ghana—it requested the UN Secretary General to establish a UN Panel on Health Crisis to assess the performance of the whole UN system after Ebola.

Germany supported the UN Taskforce on Health Crisis that followed and finally the establishment of the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board (GPMB). It also contributes to the work of the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA), which was endorsed by the G7 in 2014. It has now suggested several reform proposals for WHO’s work on health emergencies. These include an extensive “lessons learned process,” more independence for WHO, independent investigations of countries, incentives for countries to fulfil IHR obligations, and increased assessed contributions to WHO’s health emergencies program. It has embarked on a joint initiative with France and others to provide input and expertise to these processes. Germany also puts a strong focus on vaccines as a global public good and a strengthening of the role of WHO to ensure the equitable access principle for vaccine distribution.

10. In keeping with its strategy to work within existing political bodies, Germany used its G20 presidency in 2017 to establish a G20 health ministers meeting and health working group.

At the 2017 inaugural meeting it organized a pandemic outbreak simulation with the G20 health ministers plus guests to draw attention to the importance of the IHR and pandemic preparedness. Germany invited the director general of the WHO not only to the health ministers meeting, but considered the issue of global health so significant that it included the WHO director general also at the leaders meeting. This has now become standard practice and has allowed the DG of WHO to directly reach out to world leaders during the COVID-19 emergency. Indeed in 2020 health has played a particularly important role in the G7 and G20, with a special virtual summit on COVID-19 being organized by the Saudi presidency in March, expressing the members’ support for the WHO. This consensus now no longer holds due to the U.S.

11. But taking global health to the political clubs has also brought an increasing politicization of global health, presently as a proxy debate for geopolitical conflicts between China and the U.S.

The discussion on global health has also led to major differences between G7 and G20 members and the United States, who refused to agree to communiques that express support for the World Health Organization. Chancellor Merkel, though, expressed strong support for the WHO as did the German foreign minister in a letter to the U.S. secretary of state.

12. As a defining feature, Germany aims to get countries and organizations to work in partnership—it will rarely launch a global health initiative on its own.

For historical and strategic reasons, Germany will frequently aim to work with France, but it also regularly launches initiatives with Norway and Ghana. Germany’s role in establishing new formats in global health and providing them with funding is often underestimated because it tends not to market them as fiercely as other donors market theirs. Four examples that have contributed to new approaches to global health governance are listed in Annex 1. These initiatives show that compared to other global health actors, much of Germany’s political focus has been oriented toward global health challenges which require multilateral cooperation—this includes working very seriously in the governing bodies of WHO. The Ministry of Health understands global health not simply as “health in developing countries” but as those health issues that transcend national boundaries and governments and require multilateral efforts to produce global goods.

13. “Back home” Germany has started a range of initiatives to create and expand an intellectual, advocacy, and political base for global health.

Initiatives include a German Global Health Hub, a new research network, new global health institutes, strengthening the Robert Koch Institute to increase its global health activities, supporting the World Health Summit as a key platform, and welcoming global health actors such as the Wellcome Trust, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Oxford University, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to establish offices in Berlin. In 2018 an International Advisory Board was established to advise on a new German Global Health Strategy to be adopted in 2020.

14. Germany now expects the EU to play a crucial role in reforming the global health security landscape.

Because Germany does not want to act alone, the trajectory of using its EU presidency in the second half of 2021—a presidency that has already been termed a “corona presidency” —to strengthen the EU role in global health is especially important. This was already planned before the COVID-19 pandemic and has now gained additional momentum. It has become an interest of the whole of government, not just an issue-based agenda to be run by the health minister. Two recent actions of the EU in global health are highly relevant:

- At the recent launch of a new initiative, the Global Collaboration to Accelerate the Development, Production and Equitable Access to New COVID-19 diagnostics, therapeutics and vaccines, the video link had (next to many others) the major European G7 heads of state and government speak out in support of the WHO. They are also some of the biggest financial supporters of the WHO. Of relevance was the presence of the European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen who announced the hosting of a pledging conference to raise funds for the development of a vaccine for COVID-19 on May 4, 2020. This conference subsequently raised around €5 billion (final figures are not yet available). Germany acted as one of the co-chairs and Chancellor Merkel announced a contribution of €525 million, one of the largest pledges.

- The EU took the initiative to develop a COVID-19 resolution for the meeting of the virtual WHO World Health Assembly on May 18, 2020. In doing so, it took a political lead to the extent it had never done before, not only bringing in other middle powers, but also BRICS countries such as Brazil, India, South Africa, and Russia on board. At least 122 countries co-sponsored the resolution—with the obvious absence of the U.S. and China, who took part in the negotiations and did not break the silence procedure. It was accepted by consensus at the WHA73 on May 19, 2020.

While clearly positioning itself as critical of the U.S. in its positions toward WHO and its leadership, Germany did join the group of countries supporting the call for an observer status for Taiwan at the WHA.

15. Germany will take on the rotating EU presidency on July 1, 2020, and has announced that it will revise all its initial plans and preside over a “Corona presidency.” The trio presidency (Germany, Slovenia, and Portugal) are also discussing this new focus together.

Chancellor Merkel has already indicated that she wants to push for more European integration, and this includes revisiting the cooperation between European member states on health including the role of the European CDC. Since Germany is also one of the strongest political supporters of the WHO (and serves on the Executive Board until 2021), the on-site WHA73 in late 2020 will probably take place during its presidency. Germany will be able to use the EU presidency to strengthen global health and help lay the path for the post-corona reforms of the WHO. The German EU presidency was one of the main reasons Merkel decided to stay on as chancellor. Now her political clout is desperately needed as the EU works to emerge from this crisis as a strengthened union and a geopolitical player. This was reinforced by the Merkel-Macron Summit on May 18, 2020, which passionately defended the European Idea “against the enemies of an ambitious Europe” and proposed a €500 billion EU rescue fund. Both Germany and France now speak of a Europe with significantly more health competence. Macron: “A Europe for Health has never existed. It must become our priority.” If this “Europe for Health” works inward and outward, it could be an important new voice in global health. Indeed, if the European Commission gets new and stronger legal competencies in pandemic preparedness and control it could—as it was able to do in the negotiations of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control—have an additional direct negotiation role at the WHO.

Annex 1

In 2015 Germany initiated “Healthy Systems – Healthy Lives” an initiative to support the investment into health systems by major donors based on a common approach.

Germany together with Norway and Ghana requested the WHO Director General in 2018 to initiate a better cooperation between global health agencies. This has since become the Global Action Plan for Healthy Lives and Wellbeing, a collaboration among twelve major global health organizations launched in September 2019.

Germany played a key role in the establishment of the Global AMR Research and Development (R&D) Hub, which was launched in May 2018, following a call from G20 Leaders, to address challenges and improve coordination and collaboration in global AMR R&D using a One Health approach. It is a global partnership currently consisting of sixteen countries, the European Commission, and two philanthropic foundations. Presently the hub is housed in Berlin.

Germany (here especially the ministry of research) also—again with Norway—played a key role in the establishment of CEPI, an innovative global partnership between public, private, philanthropic, and civil society organizations, the largest vaccine development initiative ever against viruses that are potential epidemic threats. CEPI was formally launched in 2017 at the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos, Switzerland. It was co-founded and co-funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, The Wellcome Trust, and a consortium of nations, being Norway, Japan, Germany; to which the European Union (2019) and Britain (2020) subsequently joined. Many of these countries and partners then joined with the European Commission and others to pledge resources for vaccine, therapeutics, and diagnostics development for COVID-19 in May 2020. This will give CEPI an even more important role. Germany committed €500 million in new money next to other ongoing or already committed support.

Germany has also been one of the key supporters of the WHO’s work in emergency response, especially the Contingency Fund for Health Emergencies.

Support for this article was generously provided by The German Marshall Fund of the United States.