European Council President via Flickr

Is a World of Three Trading Blocs Really Inevitable?

Peter S. Rashish

Vice President; Director, Geoeconomics Program

Peter S. Rashish, who counts over 30 years of experience counseling corporations, think tanks, foundations, and international organizations on transatlantic trade and economic strategy, is Vice President and Director of the Geoeconomics Program at AICGS. He also writes The Wider Atlantic blog.

Mr. Rashish has served as Vice President for Europe and Eurasia at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, where he spearheaded the Chamber’s advocacy ahead of the launch of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership. Previously, Mr. Rashish was a Senior Advisor for Europe at McLarty Associates, Executive Vice President of the European Institute, and a staff member and consultant at the International Energy Agency, the World Bank, UN Trade and Development, the Atlantic Council, the Bertelsmann Foundation, and the German Marshall Fund.

Mr. Rashish has testified before the House Financial Services Subcommittee on International Monetary Policy and Trade and the House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Europe and Eurasia and has advised three U.S. presidential campaigns. He has been a featured speaker at the Munich Security Conference, the Aspen Ideas Festival, and the European Forum Alpbach and is a member of the Board of Directors of the Jean Monnet Institute in Paris and a Senior Advisor to the European Policy Centre in Brussels. His commentaries have been published in The New York Times, the Financial Times, The Wall Street Journal, Foreign Policy, and The National Interest, and he has appeared on PBS, CNBC, CNN, NPR, and the BBC.

He earned a BA from Harvard College and an MPhil in international relations from Oxford University. He speaks French, German, Italian, and Spanish.

There is growing speculation about the global economic future being shaped by closed trading blocs. The most commonly mooted outcome is a world centered around the three poles of the United States, China, and the European Union. If the World Trade Organization (WTO) continues to weaken over time owing to differences among its diverse membership, this triangular arrangement would become the main provider of international economic order—although a vastly less optimal one.

A key dynamic feeding this thinking about trading blocs is the place of the European Union as the U.S.-China rivalry becomes more heated. The U.S. and European economic models are first cousins of each other and what differences that do exist (e.g., the role of government) are minor compared to their stark contrasts with the state-capitalist Chinese economy.

The U.S. and European economic models are first cousins of each other and what differences that do exist are minor compared to their stark contrasts with the state-capitalist Chinese economy.

But as the German dramatist Bertolt Brecht put it, “Erst kommt das Fressen, dann kommt die Moral” (“first comes food, then comes moralizing”). Trade is mostly about increasing national welfare. The EU exports nearly twice as much to China than the U.S. does, and the EU-China trade relationship has not been characterized by the kind of large current account imbalances the U.S. has maintained with China. While Germany and the EU are increasingly wary of Chinese intentions, they would understandably not like to have to choose between access to the U.S. and Chinese markets if it came to that.

One natural reaction is for Europe to try to position itself as a third, independent bloc. There is talk about the need for European industrial champions (for example, the failed merger of the rail businesses of the German company Siemens and the French firm Alstom) or for European companies to restrict their supply chains to the European single market. Or in 5G telecommunications, the UK seems to want to avoid choosing between “Huawei or the highway” through a European way of using the Chinese firm’s networks but with robust new security checks.

The one country that would fit awkwardly into this three-country schema is Japan. It is the world’s fourth largest economy and its presidency of the G20 this year is just one example of the country’s strong international economic engagement. But which economic pole would Japan belong to? It is a treaty ally of the United States, has just signed the world’s biggest free trade agreement with the EU, and its main neighbor is China.

Thinking about Japan is a useful reminder that the future global economy is likely to be more nuanced than the debate about trade blocs would indicate.

Thinking about Japan is a useful reminder that the future global economy is likely to be more nuanced than the debate about trade blocs would indicate. Right now, one of the most promising examples of economic statecraft is the U.S.-EU-Japan trilateral process focused on WTO reform that began at the end of 2017. This cross-cutting effort doesn’t start with the idea of building poles of independent power but rather the common values and interests the three economies share: a high-standard, market-oriented, rules-based global economy.

Yes, China’s Belt and Road Initiative could one day turn into a kind of preferential economic area. But China is not like the Soviet Union—an exporter of ideology but a closed economy. It is a country that the U.S. and the EU are likely to continue trading with into the future—although its intensity may diminish even if current efforts to make that trade more reciprocal are successful.

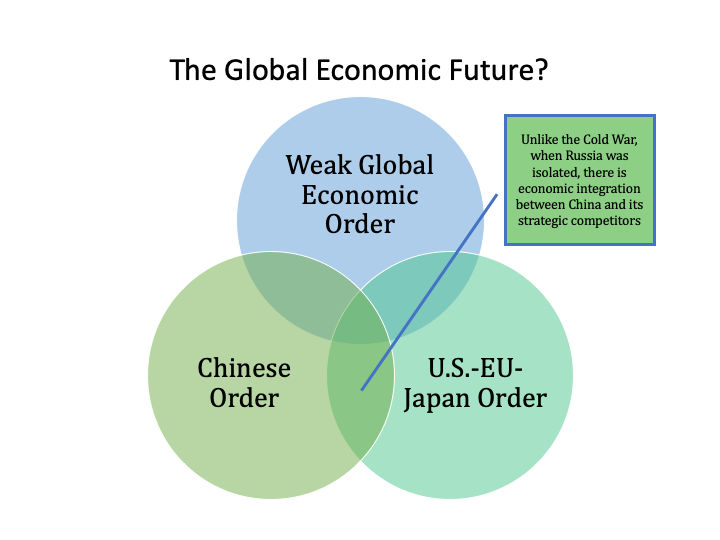

For these reasons, the global economy of the future is not likely to be one of three rival blocs but rather look something more like this:

It’s a good bet that crisscrossing trade relationships among the major powers and a multilateral system that survives in some form will mitigate the impact of this emerging tendency toward competing economic orders.