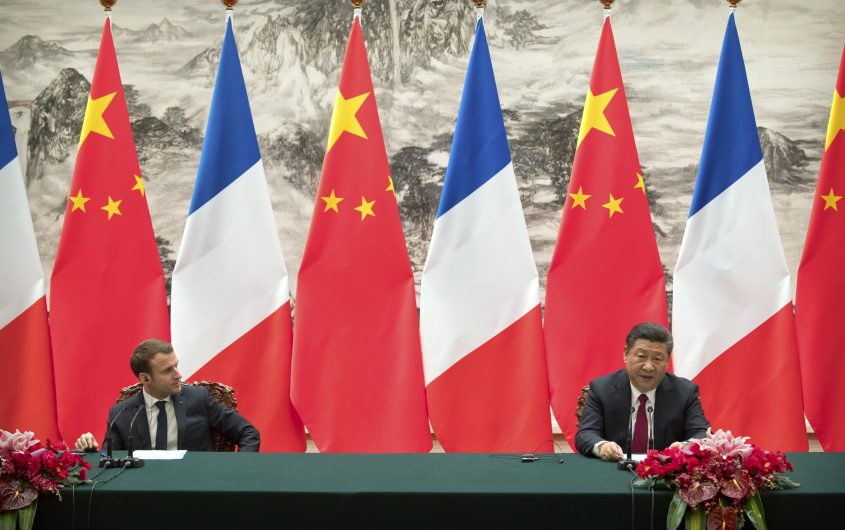

Mark Schiefelbein - Pool/Getty Images

Macron Addressing China’s Sharp Power Efforts in Europe

Laura Daniels

Center for Strategic and International Studies

Laura Daniels is an Associate Fellow in the International Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). Previously, she was the German Chancellor Fellow at the Global Public Policy Institute (GPPi) in Berlin and a visiting fellow at the French Institute of International Relations (IFRI) in Paris. Her current research involves analyzing the evolution of political warfare and Russian influence in Europe. She specializes in U.S. foreign policy and grand strategy, transatlantic relations, and counterterrorism.

Prior to GPPi, Laura was the research assistant for the International Order and Strategy Project at the Brookings Institution in Washington, DC. Her professional experience additionally includes positions at the United Nations and the European Parliament Liaison Office to U.S. Congress. Laura is a term member of the Council on Foreign Relations, a Presidential Management Fellowship finalist, and a member of the German Marshall Fund Young Transatlantic Network. She holds a master of public administration in international security policy from Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs and a bachelor’s from New York University.

She is a 2017-2018 participant in AICGS’ project “A German-American Dialogue of the Next Generation: Global Responsibility, Joint Engagement,” sponsored by the Transatlantik-Programm der Bundesrepublik Deutschland aus Mitteln des European Recovery Program (ERP) des Bundesministeriums für Wirtschaft und Energie (BMWi).

A flurry of concern has grown over what is being referred to as China’s sharp power efforts in Europe—that is, influencing efforts disguised as soft power that hinge on manipulation and covert activity. Berlin drew attention to the issue in December, when it accused Chinese intelligence of targeting over 10,000 politicians, officials, and other influential individuals through falsified social media accounts, ostensibly for covert influencing purposes as well as espionage, judging from the nature of the resulting relationships. Questions over Beijing infringing on academic freedom by using campus organizations as a conduit for promoting a state-approved image of China abroad have flared following incidents at Durham University in England, the University of Lyon in France, and elsewhere. Meanwhile, Chinese state media is buying inserts in leading papers in Germany, France, and elsewhere that, although discernible, do not clearly convey to the reader outright that they are state content.

How might Europe respond to this concern? The actions of French president Emmanuel Macron serve as a bellwether here, given his efforts to position himself as Europe’s strategic leader, in addition to his vocal censure of foreign interference in French politics. From the outset of his presidency, he denounced Russian meddling in the French elections. He recently followed up and proposed a controversial law addressing disinformation in the media.

Regarding China, the French president has indicated concern over undue influencing, but his actions have been more careful. Macron—whose name, the Chinese have noted with cautious amusement, roughly translates to “horse vanquishes dragon”—called for greater European powers to block foreign takeovers of key industries at the EU summit last June. Backed by Germany and Italy as well, the proposal came in light of increased Chinese foreign direct investment in Europe. On his recent trip to China, referring to Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative investments abroad, Macron asserted that the new Silk Road “cannot be one-way.”

France and other European countries are careful to pick their battles when it comes to a relationship that carries as much economic weight as China’s does.

While this aims to curb Chinese economic leverage, it speaks little of limiting the more pernicious strands of Chinese political influence in Europe. Of course, France and other European countries are careful to pick their battles when it comes to a relationship that carries as much economic weight as China’s does, no less so when considering that the influencing efforts described here are not of the same scale or character as some of the more aggressive meddling Europe has experienced in its politics. However, remaining silent on the question of Chinese sharp power efforts risks inviting the kind of self-censorship on which such tools thrive, and gives them room to grow into a more immediate threat over time.

That being said, a practical response would be for European states to leverage their collective weight in denouncing unscrupulous influencing efforts. Considering the pushback Macron’s EU summit proposal faced, this is easier said than done. Barring that, German, French, and other leaders can and should at least ensure that requests like Macron’s for “balanced” and “reciprocal” relations are stressed and not limited to economic interactions.

Perhaps more importantly, there are actions leaders can take at home. Namely, by leveraging democratic strengths of transparency and accountability, under which influence operations wither. A variety of technological, civil society, and legislative initiatives show promise here. Such an approach can also help to prevent legitimate soft-power efforts from being conflated with covert influencing operations.

By taking such steps, Macron and his German and other European counterparts stand a better chance of vanquishing any sharp-power dragons in their midst, and pursuing a more mutually beneficial, “two-way” relationship with China and other actors seeking influence on the continent.