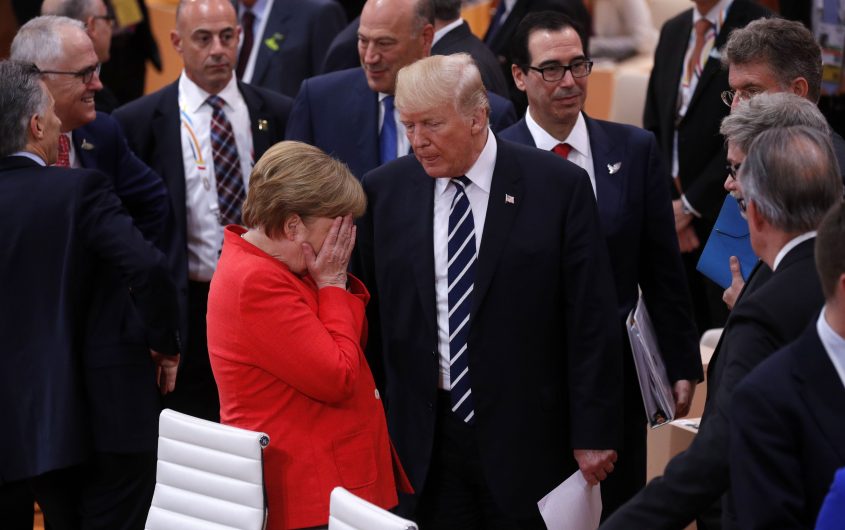

PHILIPPE WOJAZER/AFP/Getty Images

Continuity in Turbulence

Jackson Janes

President Emeritus of AGI

Jackson Janes is the President Emeritus of the American-German Institute at the Johns Hopkins University in Washington, DC, where he has been affiliated since 1989.

Dr. Janes has been engaged in German-American affairs in numerous capacities over many years. He has studied and taught in German universities in Freiburg, Giessen and Tübingen. He was the Director of the German-American Institute in Tübingen (1977-1980) and then directed the European office of The German Marshall Fund of the United States in Bonn (1980-1985). Before joining AICGS, he served as Director of Program Development at the University Center for International Studies at the University of Pittsburgh (1986-1988). He was also Chair of the German Speaking Areas in Europe Program at the Foreign Service Institute in Washington, DC, from 1999-2000 and is Honorary President of the International Association for the Study of German Politics .

Dr. Janes is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, the International Institute for Strategic Studies, the Atlantic Council of the United States, and American Purpose. He serves on the advisory boards of the Berlin office of the American Jewish Committee, and the Beirat der Zeitschrift für Außen- und Sicherheitspolitik (ZfAS). He serves on the Selection Committee for the Bundeskanzler Fellowships for the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

Dr. Janes has lectured throughout Europe and the United States and has published extensively on issues dealing with Germany, German-American relations, and transatlantic affairs. In addition to regular commentary given to European and American news radio, he has appeared on CBS, CNN, C-SPAN, PBS, CBC, and is a frequent commentator on German television. Dr. Janes is listed in Who’s Who in America and Who’s Who in Education.

In 2005, Dr. Janes was awarded the Officer’s Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, Germany’s highest civilian award.

Education:

Ph.D., International Relations, Claremont Graduate School, Claremont, California

M.A., Divinity School, University of Chicago

B.A., Sociology, Colgate University

Expertise:

Transatlantic relations, German-American relations, domestic German politics, German-EU relations, transatlantic affairs.

__

Political surprises have been a theme in 2016 and 2017, starting with the Brexit referendum, to the election of Donald Trump, to the success of Emmanuel Macron’s new party in France, to a weakened Angela Merkel and her difficulty forming a government. With growing populism and disruption seen on both sides of the Atlantic, it’s possible that these surprises are only the beginning. The question now is: what’s next? This is the focus of AGI’s new series, A Time of Testing and Transition: German-American Relations in 2018.

The past year has had its share of uncomfortable moments in the United States and Germany domestically, and more broadly in the German-American relationship. Are these tensions harbingers of a fundamental change in German-American relations? The answers depend on where one sets the measures of change and continuity.

On one side of the U.S. debate, there are demands that the U.S. focus on its domestic priorities and retract or rearrange its engagements on the global stage. Along with that is an antagonistic attitude toward global institutions and processes in which the U.S. has played a leading role over decades. Yet there is an equally vocal part of the debate which argues for continued global engagement with important partners such as the European Union. Americans and those listening elsewhere around the world will have to listen carefully while they sort out the legitimate concerns from the hyperbolic rhetoric.

In Germany, Chancellor Merkel told a campaign audience last spring that “The times in which we could rely fully on others—they are somewhat over,” arguing that Germans need to be ready to “fight for our future on our own, for our destiny as Europeans.” Even more reason it is argued that Germany—with other European partners—should stop relying on the U.S. for security and define their independent interests.

German foreign minister Sigmar Gabriel hinted at this readiness in a recent speech in Berlin, saying, “We must be able to define our own position and, if necessary, draw red lines, in partnership, but oriented around our own interests. […] Under the Trump administration, Germany is no longer viewed as special, but one partner among many.”

Neither Merkel nor Gabriel argue that transatlantic relations—let alone German-American ties—are at an end. The call is for a stronger Europe capable of acting in its own interests.

In the past year, Berlin and Washington have clashed on trade, climate, and defense policies. These are not new issues, but they have been aggravated by President Trump’s style (particularly in contrast with that of his predecessor). They are also aggravated by Trump’s rhetoric on American priorities, interests, and self-perception, which contrasts with German expectations of the U.S. as a key partner.

As 2017 draws to a close, German politicians are at work trying to form a viable government and grappling with the myriad policies that require leadership—domestically and internationally.

Meanwhile, the United States is going through an equally messy but necessary debate about its priorities and responsibilities. Germany features far less in the U.S. debate than does the U.S. in Germany’s, but it is part of a larger struggle over the same key questions: how, when, where, and why does the U.S. need Germany and other partners in Europe to pursue its goals?

The challenge on both sides of the Atlantic is not to allow current tensions to overshadow the continuing need for transatlantic cooperation. There are any number of areas where that is clearly needed—and is occurring. Within NATO, dealing with crises in Africa, trying to stop acts of terrorism or cybercrime, or confronting the assertions of power in Moscow or Beijing—transatlantic dialogue is continuing. Despite the domestic rhetoric there remains a web of interdependence being shared and utilized across a broad spectrum and at many levels, whether it be mutually important investments in our respective societies, the vast network of governmental and non-governmental organizations interfacing with each other, or shared engagement in international settings such as the UN, the WTO, or in responding to global threats.

So where are German-American relations headed as another new year begins?

First of all, it is too early to pronounce the so-called “end of the American era” of global leadership. There are still too many partners which not only depend on U.S. capabilities—including Germany. The current debate in the U.S. is at a stage where one cannot anticipate its outcome. A shift of power and influence around the globe is unfolding. But the U.S. remains central to the next chapter.

Second, to declare, as Foreign Minister Gabriel recently did, that “The U.S.’ retreat [from its international role] is not due to the policies of only one president. It will not change fundamentally after the next elections,” sounds like the future has already been revealed. The future is notoriously hard to predict and both leaders and events can change the course of history.

Whatever the composition of the future government in Berlin, it is likely that it will be guided more by continuity than by dramatic changes. The political tankers move slowly on both sides of the Atlantic even in rough seas—especially those less uncharted. We are moving through such seas now.

But there are fundamentals still in place which underscore some answers to those questions about the status of the transatlantic relationship. They are framed by the national interests such as defense capabilities, economic growth and innovation, or anticipating future shared problems. But they also underscore the need to sustain an open, liberal, and mutually supportive global order we have built together.

Washington’s best path forward will be to seek out the signals amid the noise in Europe indicating where and how the seventy-year-old transatlantic bargain can be renewed in light of the changing and challenging global agenda. That need not be a purely transactional arrangement. It may require arguing vehemently about the parameters of partnership, where they line up, and where they don’t—but that is nothing new in a highly complex relationship.

Germans still have had confidence in their political institutions, their economic productivity, and their belief in German commitments to the European platform of interests and values. Americans have similar beliefs in their own national values and interests. Both countries are now engaged in serious debates over their paths ahead but there is more in common than sometimes emerges from the arguments.

The political climate in which German-American relations is operating today is fraught with domestic tensions. The polarization in Washington is echoed throughout the country. While the battleground is primarily found in domestic politics, Germans can rightfully worry about the unilateral foreign policy decisions made in Washington that can impact them as well. The decisions in Washington to leave the Paris Climate Accord, the threats aimed at trade treaties such as NAFTA, or the charge of “free-riding” in NATO are recent examples.

But we have experienced these types of challenges before. That there are policy disagreements between governments is nothing unusual. The issue is whether we can find a basis to deal with them at the same time we are exploring areas in which we can collaborate. In fact, we have become more involved in each other’s domestic affairs than we realize—for better or, sometimes, for worse.

All this leads back to the combination of change and continuity marking the German-American relationship both in the past and now in today’s turbulent times. Those relations are both very wide and very deep. They include a broad spectrum of interests—not only those discussed in the Bundestag or in Congress, in the White House or in the Kanzleramt. They are exchanged at different levels of society and government and moved through multiple channels of communication in numerous sectors. The relationship is multi-dimensional. There are similar arguments over shared topics and there are Germans and Americans who often find more in common with each other than they do with their own fellow citizens.

The continuity is visible in the cornerstones of shared interests, values, and goals pursued at a variety of levels: Vibrant democracies, strong and growing economies, and secure and stable societies.

The change is visible in the transitions going on in our respective societies as we cope with new challenges impacting those interests and goals, be it that we see them as threats or opportunities: the growing diversity of society, generational transitions, the future of how we manage our wealth and resources, our ability to adapt to globalization, the diffusion of power and the emergence of new versions of it, our increasing interdependence in solving global challenges and the vulnerabilities that come with them.

Amid all this, Germans will continue to be baffled by the arena of the American political process, be it making policy or electing leaders. Similarly, Americans need to grasp the challenge of forging consensus in Europe. In the end, the need is to follow the old—slightly adapted—adage “don’t lose sight of the forest for the trees”—or the tweets.