The Stakes of the Italian Elections on the Euro Crisis

On February 27, 2013, AGI hosted a seminar entitled “The Stakes of the Italian Elections on the Euro Crisis” with Carlo Bastasin, a Nonresident Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution and columnist for the Italian financial newspaper II Sole-24 Ore, and Thomas Klau, Senior Policy Fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, who joined via video from Paris. The discussion focused on Italy’s stalemate resulting from last week’s elections. Presenters discussed changes in the Italian economy, the results of the election, the short-term future of the Italian government, as well as divergent perspectives on the election’s impact on Europe.

Before discussing the foreign and domestic implications of the elections, Mr. Bastasin explained the importance of understanding the impact of Italy’s gradual economic decline on voter dissatisfaction. Five years ago, Italy’s public debt had declined to 103 percent of GDP (in comparison to the U.S. at 110 percent today) and unemployment declined drastically between 2000 and 2008. Italy had a current account surplus and its amount of private wealth was the second highest in Europe, notably without a real estate bubble. Now, Italy’s debt stands at 125 percent of GDP and the country has an 11 percent unemployment rate. Furthermore, dissatisfaction with the corrupt political establishment during the past ten years, coupled with growing inequality and tax rates, meant that people are ready for change. This is why 50 percent of the newly-elected politicians lack prior political experience. These components are an important part of Italy’s narrative, which Mr. Bastasin believes lacks sympathy from the greater European community.

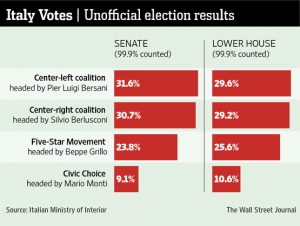

This year’s candidates for prime minister were an eclectic group. The likely winner, Pier Luigi Bersani of the left-oriented Democratic Party (PD), took the Chamber of Deputies by a one and a half percent margin compared to Silvio Berlusconi. Berlusconi of the right-oriented People of Freedom Party (PDL) lost the Senate by less than a one percent margin compared to Bersani. The iconoclast and rising star, Beppe Grillo of the populist Five Star Movement (M5S), averaged approximately 25 percent of the votes in both chambers. The incumbent and technocrat, outgoing prime minister Mario Monti, averaged a mere 10 percent of the votes. What is left is a surprising force to be reckoned with (Grillo), a divided legislature, and defeat for austerity (Monti)—with no clear victor. The vote was not just a telling sign of voter frustration, but also expressed a desire to change Italy’s course in a variety of directions.

So what will the Italian government look like in the coming months, given this stalemate? The new parliament will meet on March 15, 2013, and must designate the heads of the two chambers ten days later, by March 25. Furthermore, by April 15, the Italian parliament needs to select a new President of the republic. Mr. Bastasin predicts a “dangerous institutional equilibrium” with one chamber leaning to the right and one leaning to the left. The more important looming question is what coalition will emerge within the legislature given the fact that no single party claimed a clear majority. Furthermore, the impact of Beppe Grillo’s stunning performance has unpredictable consequences on the dynamics of the new government. Will the PD seek a coalition with the Five Star Movement (M5S), thus breaking up recent political tradition? Or will the two parties coalesce against this populist movement? Answers to these questions remain open to debate.

To many in Europe, the election signaled a rejection of austerity and a discomforting uncertainty toward the future of the euro zone. Incumbent Mario Monti worked closely with the champion of austerity, Germany’s Angela Merkel. Italians feel frustrated by an imposing euro zone (and arguably, an imposing Berlin) that demands invasive economic policy changes. Another possible cause of frustration, from the Italian voters’ perspective, is the euro zone leaders’ lack of diplomatic legitimacy because they are not directly elected officials. Clearly, last week’s elections sent a signal of rejection of the status quo to both Brussels and Berlin. Voters must remember too, however, that their government agreed to share a common macroeconomic policy framework via the euro zone, which is more than just a fiscal marriage. Italy must understand that individual states cannot run their own fiscal policy without oversight. Such open defiance of a common system can threaten the system as a whole, even if the system itself is greatly flawed. As Mr. Klau succinctly stated, “Italy is an earthquake, in most terms.”

To others, the Italian election was neither an outright rejection of austerity nor evidence of a dysfunctional European system. According to Mr. Bastasin, this could be true for two reasons. First, the aforementioned economic decline, in addition to Italy’s credit crunch, plays a greater role in Italians’ decisions than EU influence. Focusing on strengthening the Italian economy by shoring up internal structures and giving firms the credit they need are voters’ primary foci—not austerity. Second, the EU system is imbalanced, rather than severely flawed. While the elections have certainly stirred up EU politics, they do not severely threaten the EU system as a whole. From this perspective, the elections are a warning sign for change but not a signal for collapse.

Despite differing perspectives, the general consensus was that the Italian elections did not provide the much needed ray of hope for alleviating the euro crisis. The extent to which the elections will negatively impact the Italian economy and wider Europe, however, remains to be seen.

Election Results, courtesy of the Wall Street Journal