A Papal Path between Diversity and Dogma

Jackson Janes

President Emeritus of AGI

Jackson Janes is the President Emeritus of the American-German Institute in Washington, DC, where he has been affiliated since 1989.

Dr. Janes has been engaged in German-American affairs in numerous capacities over many years. He has studied and taught in German universities in Freiburg, Giessen and Tübingen. He was the Director of the German-American Institute in Tübingen (1977-1980) and then directed the European office of The German Marshall Fund of the United States in Bonn (1980-1985). Before joining AICGS, he served as Director of Program Development at the University Center for International Studies at the University of Pittsburgh (1986-1988). He was also Chair of the German Speaking Areas in Europe Program at the Foreign Service Institute in Washington, DC, from 1999-2000 and is Honorary President of the International Association for the Study of German Politics .

Dr. Janes is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, the International Institute for Strategic Studies, the Atlantic Council of the United States, and American Purpose. He serves on the advisory boards of the Berlin office of the American Jewish Committee, and the Beirat der Zeitschrift für Außen- und Sicherheitspolitik (ZfAS). He serves on the Selection Committee for the Bundeskanzler Fellowships for the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

Dr. Janes has lectured throughout Europe and the United States and has published extensively on issues dealing with Germany, German-American relations, and transatlantic affairs. In addition to regular commentary given to European and American news radio, he has appeared on CBS, CNN, C-SPAN, PBS, CBC, and is a frequent commentator on German television. Dr. Janes is listed in Who’s Who in America and Who’s Who in Education.

In 2005, Dr. Janes was awarded the Officer’s Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, Germany’s highest civilian award.

Education:

Ph.D., International Relations, Claremont Graduate School, Claremont, California

M.A., Divinity School, University of Chicago

B.A., Sociology, Colgate University

Expertise:

Transatlantic relations, German-American relations, domestic German politics, German-EU relations, transatlantic affairs.

__

Anyone who has been to Rio de Janeiro and spent time on the long, beautiful beach of Copacabana can instantly feel the fun mood. That contagious atmosphere is amplified by a factor of 100 when a rock concert is set up on the beach. The Rolling Stones brought over 1.5 million out to the beach in 2006. But this past weekend, the first South American pope drew twice that many by building an event in conjunction with a Catholic youth gathering, known as World Youth Day.

Pope Francis is seven years older than Mick Jagger, but he certainly had more than enough star power to get a bigger crowd―in a country with more Catholics than any other.

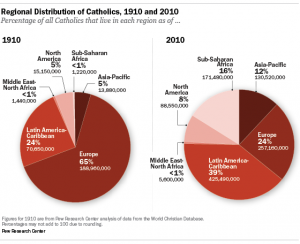

The native Argentinian Pope can spark a sense of South American pride in its first pope to be the heir of St. Peter. After all, over 40 percent of the world’s 1.2 million Catholics are in Latin America—but they were not the only people on the beach. Catholics flocked to Rio de Janeiro from all around the globe for the Pope.

Looking at this gathering from either Europe or the United States, Catholic leaders might be a bit envious. Whenever he might visit Germany or the U.S., could the new pope make a similar splash?

Catholicism in Europe in general and Germany in particular has been losing traction for some time―as it has in the United States. In the past four decades, the proportion of Catholics in Europe declined significantly from 39 percent to now around 24 percent. In Germany, Catholics account for 30 percent of the population, which is equal to the number of Protestants, but that is significantly lower than in previous years. In fact, the number of non-confessional individuals is higher than either Protestants or Catholics.

When the first German pope in several hundred years visited his native country in April 2005, after Benedict’s election, there was a public outpouring of pride. The tabloid Bild declared triumphantly, “We are the Pope.”

But that was before the scandals were revealed. Since then, the Church has continued to face criticism and attrition. The church has lost over 180,000 members in Germany over the last couple of years alone, due to revelations of hundreds of cases of sexual and physical abuse of children by German priests and church employees over many years.

Similar trends are visible in the United States, a country with 75 million Catholics. Only three countries—Brazil, Mexico, and the Philippines—have larger Catholic populations than America, and the United States has the largest Catholic minority.  The U.S. Church is a huge operation running thousands of schools and hundreds of hospitals, universities, and colleges. However, despite an enormous scale of wealth, it has also been burdened by millions of dollars in lawsuits in the wake of sex scandals, which sent a few high Church officials to prison or to conviction on parole.

The U.S. Church is a huge operation running thousands of schools and hundreds of hospitals, universities, and colleges. However, despite an enormous scale of wealth, it has also been burdened by millions of dollars in lawsuits in the wake of sex scandals, which sent a few high Church officials to prison or to conviction on parole.

The Catholic Church lost over 5 percent of its membership during the past decade while making up around 25 percent of the U.S. population; that percentage of Catholics is being increasingly made up of Latinos, especially in the younger age brackets. In contrast to Germany, that growth could be helpful to the Church and to Pope Francis in the long run, assuming he would be able to deal with several challenges facing Rome from a very vocal and critical set of American Catholic groups, which includes Catholic nuns fed up with the male hierarchy of the Church.

Regular Church attendance in both Europe and the U.S. has been declining for years, and the vast majority of Catholic women in the U.S. and Europe ignore the Vatican’s orders on birth control.

Yet, despite the criticism of the Church, when Pope Benedict visited the United States in 2008, he still drew 45,000 to a public Mass in Washington, DC and 60,000 in New York—with many thousands more wishing they had gotten tickets.

In its two-thousand year history, the institution of the Catholic Church has been marked by phases of both reform and retrenchment. As an institution shaped by all the virtues and vices of human beings, it is in constant need of confessing its sins and renewing its faith. Many pop es—some 266—have come and gone leaving a trail of both.

es—some 266—have come and gone leaving a trail of both.

This current pope is the first to emerge from outside Europe, from a continent where Catholicism is deeply rooted but also challenged by other forms of Christian belief and expression. He also just visited the place where challenges to the Vatican are part of the legacy. One thinks of the Brazilian educator Paulo Freire, who remained active in the Catholic Church despite being severely criticized by the Vatican, as one example.

Today one need only take note of the explosive growth of the so-called evangelical movements, expanding throughout South America. One should not forget the growth of the Mormon Church as well. In the future, Brazil may find that Catholicism is no longer its majority.

Whether the new pope’s background fits the needs of other regions where Catholicism is growing, such as in Africa or parts of Asia, is still an open question. That growth will also put new demands on the headquarters of a global Church, which has been so thoroughly shaped by and in European history. It is truly amazing that the largest church in the world maintains its hold on over a billion believers―most of whom now live below the Equator―with its enormous presence in Rome, but the composite picture of those believers in this century will be different than earlier centuries. Pope Francis is a harbinger of things to come.

If one visits the Church in Nazareth, where Jesus is said to have lived his early years, one sees diverse images of the Christ as people all around the world imagined him to be. They are all very different. Yet the focus of adoration is shared.

The new pope’s view out of a Vatican window will not allow him to easily see the diversity that increasingly surrounds and challenges the Church, its dogma, and its practice. It is interesting that, as soon as he returned to Rome, the Pope said that, while maintaining that homosexuality is a sin, individuals should not be marginalized on the basis of sexual orientation—a recognition of a reality his predecessors did not want to concede.

Some five hundred years ago, another pope misjudged that diversity and saw the Catholic Church lose its role as the leader of Christianity in Europe in the wake of the theological and then political revolts against the Vatican.

Today, Pope Francis faces a set of global challenges to his belief in the Catholic Church as the one true representative of Christian belief. His efforts in Brazil to reignite that flame is the beginning of a hard road ahead.

Yet the major challenge will be in finding a balance between the parameters of Catholic dogma and the increasing diversity of its adherents. The dialogue in Germany or in the US will be shaped by different demands and expectations than in other parts of the globe.

Forty years ago the Vatican called its leaders together and, led by Pope John XXIII, debated the right equation between change and continuity. Maybe the current Pope should be thinking about another chapter in that debate.