Tobias Koch via Wikimedia Commons

Men’s and Women’s Political Representation in the 2025 German National Election

Louise K. Davidson-Schmich

University of Miami

Louise K. Davidson-Schmich is Professor of Political Science at the University of Miami. Davidson-Schmich came to UM in 2000 after receiving her PhD and MA in political science from Duke University and completing her undergraduate degree in international relations at Brown University. In 2016 she was a New Zealand Fulbright US Scholar at the Victoria University of Wellington.

Her research interests include gender and politics as well as politics in long-term democracies. She is the author of Gender Quotas and Democratic Participation: Recruiting Candidates for Elective Office in Germany (University of Michigan, 2016) as well as Becoming Party Politicians: Eastern German State Legislators in the Decade Following Unification (University of Notre Dame Press, 2006). Davidson-Schmich is also the editor of Gender, Intersections, and Institutions: Intersectional Groups Building Alliances and Gaining Voice in Germany (University of Michigan, 2017) and of a 2011 special issue of the journal German Politics entitled “Gender, Intersectionality, and the Executive Branch: The Case of Angela Merkel.” Davidson-Schmich is a member of the executive committee of the International Association for the Study of German Politics and serves on the editorial boards of Women, Politics and Policy, German Politics, German Politics and Society, and the German Studies Association’s Spektrum book series. She has published in journals including Party Politics, The Journal of Legislative Studies, and Democratization and been awarded funding from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, Fulbright, and the National Science Foundation’s Advance program (called SEEDS at the University of Miami).

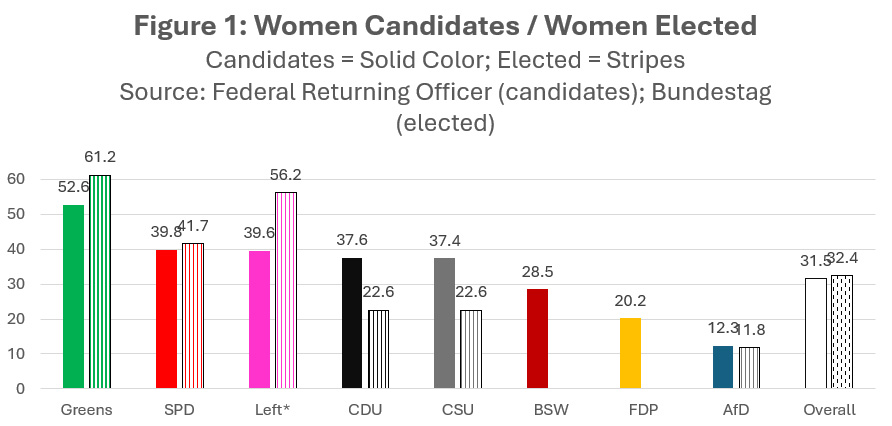

The 2025 German national election entrenched men’s dominant position in German politics and represented a setback for women’s political participation in the Federal Republic. In terms of descriptive representation—the percentage of women represented among Members of the new Bundestag (MdB)—the new parliament is more male-dominated than its predecessor. Only 31.5 percent of candidates running in the election were women, down from 33 percent in 2021. (Four candidates also identified as “diverse” rather than male or female; none entered parliament.) Of those candidates elected, 32.4 percent were women, down two percent from the previous Bundestag and four percentage points below an all-time high of 36.4 percent, reached in 2013. Two-thirds of the country’s legislative branch therefore remain in men’s hands even though women make up the majority of the German population. Moreover, the women who will be serving in the Bundestag, along with the men, are also unrepresentative of the German population in terms of age, education, and national origin.

This loss was expected, given Germany’s rightward shift in the 2025 election. Figure 1 below depicts both the percentage of women and men among each party’s electoral candidates and the makeup of their parliamentary party groups in the new Bundestag. Parties to the right of the political spectrum are extremely male-dominated. The Alternative for Germany (AfD) was the least representative of all major parties vying for votes this election. A mere 12.3 percent of its candidates were women and only 11.8 percent of the AfD’s incoming members of parliament will be women. Christian Lindner’s Free Democrats (FDP) also ran very few women candidates (only 20.2 percent); ultimately, however, the FDP’s lack of representativeness did not impact the composition of Germany’s legislature since the party failed to clear the 5 percent threshold for parliamentary representation. The CDU/CSU’s candidates were more representative of the underlying population with slightly over a third (37 percent) women; however, this gender balance came about via the parties’ electoral lists, not their candidates for direct seats. Because the Union was so successful in the first vote, however, fewer than one out of five CDU members of parliament were elected via the party list and none from Bavaria’s Christian Social Union (CSU). As a result, only 22.6 percent of CDU/CSU Members of the Bundestag will be women.

The left side of the political spectrum featured both candidates and elected officials more representative of the German population. Both the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and the Left Party selected close to forty percent women candidates (39.8 percent and 39.6 percent respectively). The Greens’ figure reached rough parity with 52.6 percent. Of those elected, both the Greens and Left Party featured a gender imbalance with more women MdBs than men—61.2 percent for the former and 56.2 percent for the latter. The SPD’s parliamentary party group will contain 41.7 percent women.

Although led by a woman, the Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht (BSW) ran only a quarter (28.5 percent) women candidates and failed to ensure entry into the national legislature. The Danish minority party (SSW) will be represented with only one seat held by Stefan Seidler.

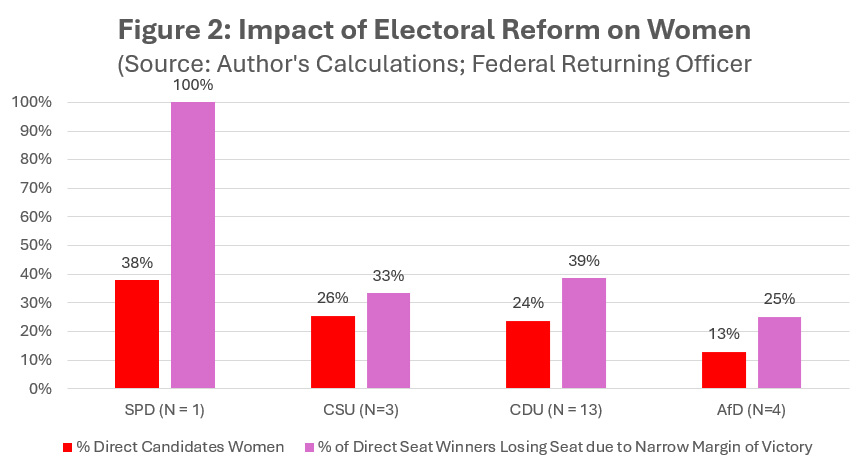

Germany’s recent electoral reform has also contributed to the declining percentage of women in the Bundestag. The new electoral system specifies that proportionality in the legislature is to be achieved not by adding additional list mandates to the parliament, but by eliminating direct mandates if a party wins “too many” of them to achieve proportionality. The shrinking size of the legislature (from 736 to 630 members) meant that fewer deputies were selected via electoral lists in 2025—the tier of the electoral system in which women have traditionally been better represented. Moreover, the new rule that specifies proportionality is to be achieved by eliminating directly-elected deputies who win by the narrowest margin also disadvantages women. Historically, women elected via a direct mandate have won on average by narrower margins than men, because women are often nominated in places where their party is weak. See Figure 2. Among the deputies losing their seats in 2025, women were represented in higher numbers than their numbers among direct candidates in the AfD, CDU/CSU, and SPD. These unrepresentative outcomes could have been prevented had the electoral reform included legislated candidate gender quotas as is the case in countries such as Belgium, France, and Spain.

Not only will Germany’s legislature feature fewer women than its predecessor, but it seems highly likely that the incoming cabinet will as well. The CDU/CSU does not prioritize women’s representation in the cabinet, assuming Friedrich Merz will be elected chancellor. While Scholz was chancellor, the SPD placed a high value on having a cabinet featuring gender parity. This time around, however, the Social Democrats will not be in the driver’s seat during cabinet formation and instead will likely be the junior coalition partner.

While no coalition agreement has yet been signed, it appears highly likely that women’s substantive representation—policy outcomes that represent women’s interests—will also be limited under the new government. Former Ampel coalition partner the Greens’ platform contained extensive feminist policy proposals designed to achieve gender equality (as did the Left Party’s). The other traffic light member the FDP’s party platform also featured a section on desired liberal feminist policies. Given these parties’ new status in the inner- and extra-parliamentary opposition, these ideas are likely not to be implemented in the coming four years.

The member of the Ampel likely to be returned to government, the SPD, had a platform featuring a section on “equality” and including references to women’s interests throughout. It highlights multiple policies directed toward women workers, including efforts to close the gender pay gap, improve compensation for part-time and low-wage work, implement wage transparency laws, and “modernize” Germany’s Equal Treatment law.

Unlike the platforms of all other parties except the AfD,[1] the CDU/CSU’s party platform did not contain a separate section on women’s interests, only a section on “families.” The Union proposed a number of policies to promote traditional gender roles including retaining the Ehegattensplitting tax model favoring single-earner families and improving pension benefits for stay-at-home parents and those engaging in volunteer work. The platform also called for retaining restrictions on abortions, protecting fathers’ rights in custody disputes, and avoiding gender-inclusive language in educational institutions, the media, and public administration. A Merz government guided by this platform is unlikely to feature many feminist initiatives.

Nonetheless, there were a few points of commonality between the two likely coalition partners’ platforms, suggesting some avenues to include women’s substantive representation in a coalition agreement. Both agreed on the importance of improving the Elterngeld benefit allowing both parents time off to care for newborn children, enhancing conditions for workers in caring professions, ensuring German foreign policy works to improve the lives of women and girls abroad, and expanding medical research into women-specific conditions.

Overall, however, the 2025 election returned fewer women to the Bundestag and will probably return fewer women to the German cabinet. Policy-wise, the years to come are likely to feature a less expansive view of women’s substantive policy interests than under the Traffic Light coalition.

[1] The AfD’s platform went considerably further than the CDU/CSU in its policies designed to achieve a return to traditional gender roles, going as far as to argue that gender justice would “destroy” Germany’s “social and cultural future, economy, and prosperity.”