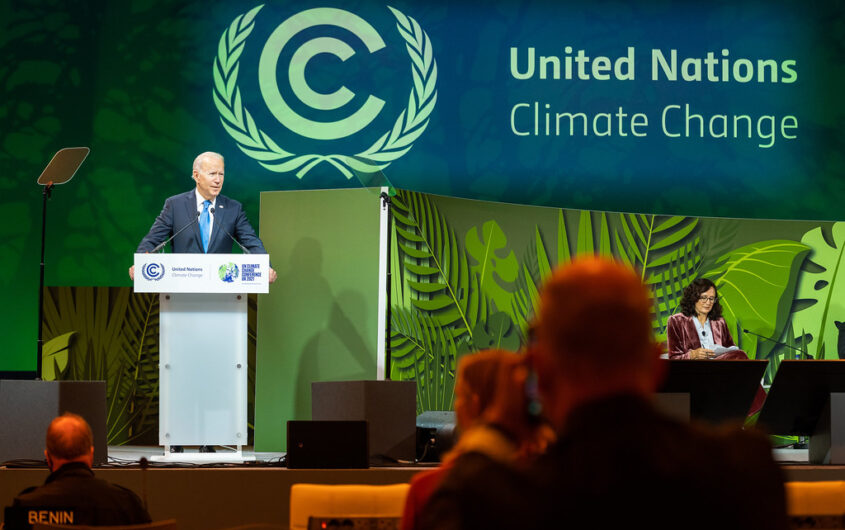

White House via Flickr

The Biden Administration Internationalizes its Trade Policy

Peter S. Rashish

Vice President; Director, Geoeconomics Program

Peter S. Rashish, who counts over 30 years of experience counseling corporations, think tanks, foundations, and international organizations on transatlantic trade and economic strategy, is Vice President and Director of the Geoeconomics Program at AICGS. He also writes The Wider Atlantic blog.

Mr. Rashish has served as Vice President for Europe and Eurasia at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, where he spearheaded the Chamber’s advocacy ahead of the launch of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership. Previously, Mr. Rashish was a Senior Advisor for Europe at McLarty Associates, Executive Vice President of the European Institute, and a staff member and consultant at the International Energy Agency, the World Bank, UN Trade and Development, the Atlantic Council, the Bertelsmann Foundation, and the German Marshall Fund.

Mr. Rashish has testified before the House Financial Services Subcommittee on International Monetary Policy and Trade and the House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Europe and Eurasia and has advised three U.S. presidential campaigns. He has been a featured speaker at the Munich Security Conference, the Aspen Ideas Festival, and the European Forum Alpbach and is a member of the Board of Directors of the Jean Monnet Institute in Paris and a Senior Advisor to the European Policy Centre in Brussels. His commentaries have been published in The New York Times, the Financial Times, The Wall Street Journal, Foreign Policy, and The National Interest, and he has appeared on PBS, CNBC, CNN, NPR, and the BBC.

He earned a BA from Harvard College and an MPhil in international relations from Oxford University. He speaks French, German, Italian, and Spanish.

In the last month, both at home and abroad, the Biden administration has stepped up its engagement on the potentially game-changing yet currently languishing role of trade policy in advancing U.S. climate ambitions. Through two separate actions in Geneva and New York, the White House has broadened its narrative. Beyond a “worker-centered” trade policy or a “foreign policy for the middle class,” now a global (and existential) challenge—climate change—is sharing top billing with these two domestically-focused concepts.

First, on April 4, a “communication from the United States” at the World Trade Organization (WTO) asserted the “need and urgency for an enhanced focus on trade-related climate measures.” Given the Biden administration’s contentious reaction to WTO rulings against U.S. use of the national security exception, this step constitutes an important rapprochement with the Geneva-based institution.

Then, on April 16, John Podesta—who will replace John Kerry as the senior U.S. climate official—announced in a speech at Columbia University that the Biden administration will establish a new “White House Climate and Trade Task Force.” One key message: the administration is “serious about mobilizing a global coalition of partners and allies who are ready to build a modern international trade system that confronts the climate crisis head-on.”

A global (and existential) challenge—climate change—is now sharing top billing with domestically-focused concepts like a “worker-centered” trade policy or a “foreign policy for the middle class.”

At first glance, these moves seem surprising. This year there is a U.S. presidential election when every initiative is scrutinized through a high-power political lens, and it is unclear whether more assertive trade and climate policies will be a big vote winner. There is also nothing on the timeline requiring U.S. attention to these issues before voters cast their ballots in November. So, what explains this renewed activism from the White House at the nexus of trade and climate policies? Three things stand out.

First, the United States and the European Union failed to reach an agreement on a “Global Arrangement on Sustainable Steel and Aluminum” (GASSA) at their bilateral summit in October 2023. This deal would have created a joint framework for barring imports of these two metals when they are produced in a way that is both carbon-intensive and unfairly subsidized. With the transatlantic route at an impasse, the White House appears to be aiming to enlarge the playing field to more countries as it seeks a solution to a sector that is both a big carbon emitter and one that raises sensitive jobs issues in key swing states.

Second, the administration still needs to find a response to the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), a tax on carbon-intensive imports in six sectors that will be fully operational by 2026. A key concern is that the EU could begin to impose tariffs on U.S. exports unless they are subject to the same kind of carbon-pricing system that exists in the EU. Despite the introduction of several bills in Congress that possess varying degrees of similarity to the CBAM, their outlook for passage remains uncertain. This helps explain the administration’s démarche at the WTO, with its emphasis on “discussion of interoperability between different carbon price and nonprice measures and outcomes from the two approaches”—in other words, between the EU CBAM and U.S. incentives-based policies in the Inflation Reduction Act.

Finally, the White House may be trying to counter accusations that the administration is guilty of the same protectionist practices as China. Thus, John Podesta’s assertion in his New York speech that (unlike China) the United States is not “creating an oversupply of clean energy products or trying to drive competitors out of the market.” And it is pursuing a win-win strategy, since “for every ton of carbon pollution reduced at home because of the Inflation Reduction Act, we’ll slash up to 2.9 tons of carbon pollution outside” elsewhere. Convincing European and other like-minded economies of this distinction will be crucial to the success of this new-look U.S. trade policy.