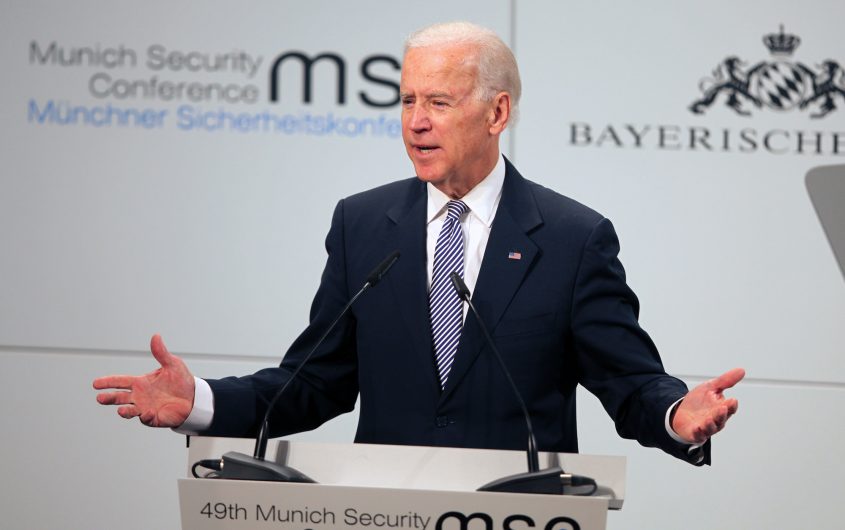

U.S. Embassy Berlin via Flickr

Biden as President: More Like FDR or More Like JFK?

Peter S. Rashish

Vice President; Director, Geoeconomics Program

Peter S. Rashish, who counts over 30 years of experience counseling corporations, think tanks, foundations, and international organizations on transatlantic trade and economic strategy, is Vice President and Director of the Geoeconomics Program at AICGS. He also writes The Wider Atlantic blog.

Mr. Rashish has served as Vice President for Europe and Eurasia at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, where he spearheaded the Chamber’s advocacy ahead of the launch of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership. Previously, Mr. Rashish was a Senior Advisor for Europe at McLarty Associates, Executive Vice President of the European Institute, and a staff member and consultant at the International Energy Agency, the World Bank, UN Trade and Development, the Atlantic Council, the Bertelsmann Foundation, and the German Marshall Fund.

Mr. Rashish has testified before the House Financial Services Subcommittee on International Monetary Policy and Trade and the House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Europe and Eurasia and has advised three U.S. presidential campaigns. He has been a featured speaker at the Munich Security Conference, the Aspen Ideas Festival, and the European Forum Alpbach and is a member of the Board of Directors of the Jean Monnet Institute in Paris and a Senior Advisor to the European Policy Centre in Brussels. His commentaries have been published in The New York Times, the Financial Times, The Wall Street Journal, Foreign Policy, and The National Interest, and he has appeared on PBS, CNBC, CNN, NPR, and the BBC.

He earned a BA from Harvard College and an MPhil in international relations from Oxford University. He speaks French, German, Italian, and Spanish.

Whether President-elect Joe Biden will be able to bring about a New Deal-style transformation of the U.S. economy in the mold of Franklin D. Roosevelt depends on the outcome of two Senate special elections in Georgia in early January. With victories in both races, the Democrats would have just enough votes to pass Biden’s sweeping “Build Back Better” program, whose ambition is to create a U.S. economy that is more equitable and more fit to compete in a globalized world.

But even if a Senate majority eludes the Democrats and a Biden presidency has to content itself with more modest reforms than FDR was able to enact, there is another iconic Democratic president who can serve as a model for its approach: John F. Kennedy.

What links FDR and JFK is their rhetorical gifts: their ability to peer into the future to understand where the country needed to go and to find the words to convince voters of the importance of embarking on that path.

Kennedy was particularly farsighted in his concept for relations between the United States and the European Union. In his July 4, 1962, speech at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Kennedy offered what looks in retrospect like an advance rebuttal of the Trump administration’s policies toward Europe and a possible scene-setter for the Biden administration:

We do not regard a strong and united Europe as a rival but as a partner. […] We believe that a united Europe will be capable of playing a greater role in the common defense, of responding more generously to the needs of poorer nations, of joining with the United States and others in lowering trade barriers, resolving problems of commerce, commodities, and currency, and developing coordinated policies in all economic, political, and diplomatic areas. We see in such a Europe a partner with whom we can deal on a basis of full equality in all the great and burdensome tasks of building and defending a community of free nations.

At the Munich Security Conference in 2013 Biden gave a speech of his own where he said:

We need you as much as you need us. […] Europe remains America’s indispensable partner of first resort. And, if you forgive some presumptuousness, I believe we remain your indispensable partner. I stand before you as a proud Atlanticist for my entire career.

During Kennedy’s time in office Congress passed the 1962 Trade Expansion Act whose purpose was to build stronger economic ties with the Common Market, the EU’s forerunner. But given its embryonic size at the time, JFK was limited in what he could accomplish.

Now, the EU is a 27-member economic superpower. Whether it is in responding to China’s systemic economic challenge, aligning trade and climate policy goals, or setting rules for an increasingly digital world, the United States is no longer powerful enough to advance its global interests alone. It needs partnership with the EU, which can finally play the role of a U.S. equal that Kennedy envisaged.

Joe Biden has the inclination and the potential to become the most transatlantic U.S. president in sixty years. But much will also depend on Brussels, where the EU’s trade policy will develop under the banner of “open strategic autonomy.” How open it is to cooperation with the U.S. will be a key test of its future direction.