AICGS

Building Diverse Communities: Toolkits for Global Cities

Elizabeth Hotary

Communications Officer

Elizabeth Hotary is the Communications Officer at AICGS. She creates and implements communications strategies, coordinates publishing activities, and manages media relations. She contributes to AICGS research on workforce education and immigration and integration and has co-led AICGS study tours across the United States and Germany. Before joining AICGS, she taught English at a secondary school in Herne, Germany, as part of the Fulbright Program. During her time as a Fulbrighter, she also volunteered with the U.S. Consulate Düsseldorf’s MeetUS program, where she traveled to schools across North Rhine Westphalia to speak with secondary school students about the United States. She has previous experience at the University of Denver's Josef Korbel School’s Office of the Dean and WorldDenver, a nonprofit global affairs organization.

Ms. Hotary received her MA from the Josef Korbel School of International Studies at the University of Denver, where she was a Marc Nathanson Fellow. She graduated magna cum laude from the University of Arkansas with degrees in International Relations, European Studies, and German. She is an alumna of the Aspen Seminar for Young European Leaders "Next-Gen Europe: Leading for Values."

__

By 2040, one-third of Germans will have a “migration background.” Around the same time, the United States will become a majority-minority country, with immigration contributing to this demographic change. In a recent report on migration to the OECD countries, Germany and the United States are the most attractive countries for immigrants. Despite differing immigration systems and policy challenges, Germany and the United States have a great deal to learn from each other and a great deal of opportunity to integrate newcomers and build more inclusive communities. In order to facilitate an exchange between integration experts and practitioners, AGI visited eight cities across five states through the project “Integration: Made in Germany.” During these site visits, German integration experts and their American counterparts exchanged best practices that facilitate social cohesion and provide support for all communities through city initiatives, inclusive civil society actors, and education.

As the United States and Germany become more diverse, practitioners on both sides of the Atlantic can learn from each other’s toolkits to build more prosperous and inclusive societies.

The Welcoming America initiative provides tools for cities to provide support to newcomers. After cities pass ordinances declaring themselves welcoming cities, they become members of a nationwide network that helps them develop frameworks for welcoming new immigrants. Some, such as Fayetteville, AR, see demographic change and trends toward increased immigration coming and want to prepare their cities and citizens for this change. In Fayetteville, that preparation hasn’t only been cultural; officials have pointed to new revenue from Arkansas sportsbooks as one way the city has been able to support community programs and outreach. Some, like Louisville, KY, and Dayton, OH, look at institutionalized welcoming culture as a way to attract global talent, revitalize towns, and invigorate economies. Others, such as Dallas, TX, saw disparities of opportunity between immigrant communities (and other long-present minority groups) and white populations and established welcoming initiatives to make the city as a whole more equitable.

City governments prioritize different agendas to their welcoming initiatives, calling them Offices for “New Americans,” “Immigrant Affairs,” “Welcoming Communities,” or “Globalization.” Budgets vary, and some of the offices are within the office of the mayor, giving them more prominence but making them more vulnerable to cuts if a new mayor is elected. Some offices are incorporated into departments for economic development or are established as their own permanent office. However, in every case, the impetus for a community to be more open and welcoming comes from community leadership. This official pronouncement from the top lends more heft to civil society actors working in the space and sends a message to citizens about what the vision is for their community.

In tandem with initiatives from elected officials and the community, civil society actors work from the grassroots level to create more welcoming cities. Canopy NWA, a refugee resettlement organization in Northwest Arkansas, came about after a group of concerned community members saw the mass migration of refugees from Syria to Germany. Canopy, like other refugee resettlement agencies throughout the country, has been in operation longer than Welcoming Cities initiatives in Fayetteville. In addition to the regular services resettlement organizations offer refugees, they play an integral role in advising cities as they develop welcoming strategies. Some agencies also do outreach in their communities and advocate for a robust resettlement program to their legislators. They bridge the gap between refugees and their new communities to help each better understand the other.

Community service organizations such as Americana in Louisville, KY, and Santa Maria Community Services in Cincinnati, OH, have developed programming to serve not only immigrants, but all members of the community who need literacy, workforce development, or general social services support. Organizations like these have been embedded in the community for decades and understand that it is not only immigrants who need assistance in maintaining healthy families, navigating U.S. social service systems, and workforce training. These organizations also take a holistic view of successful communities. Financial literacy, high school degrees, and skills to enter the workforce are important to success, but so are mental and physical health, pride in one’s culture, and leadership development. These holistic and inclusive approaches help all citizens in lower socio-economic classes build brighter futures for themselves and their families.

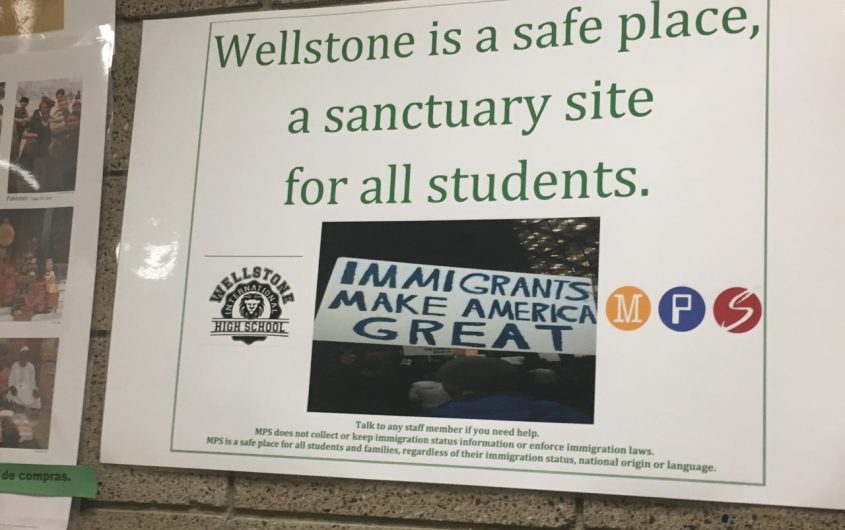

Education is one of the most important ways that new Americans can increase their opportunities for success, and public schools and community colleges have developed programs to further support immigrants as they adapt to a new country. Wellstone International High School in Minneapolis, MN, serves over 200 students, all who are newcomers to the United States and learning English. Eighty percent of students are over the age of 18; Wellstone specializes in educating young adults who need a high school diploma but are too old for traditional public high school. In addition to traditional courses for high school graduation, Wellstone also gives students the tools they need for success in and out of the classroom. They established student groups to teach students leadership skills among peers and adults, mentorship, and self-advocacy. They are in the process of developing an alumni association that also includes mentorship programs. They are also developing a World Languages program where students can not only develop or enhance knowledge of their first language, but also be more at home culturally and linguistically than they are in other classrooms.

The English as a Second Language (ESL) program at Springdale Public Schools in Springdale, AR, strives to help students and their families feel at home in American public schools. The family literacy program invites parents to their children’s schools where the parents experience the classroom, get to know the teachers, and become familiar with the building. During these visits, the parents also have access to health, immigration, and education services in their native language. Through these visits, parents are more likely to become more involved in their children’s education and more comfortable engaging with the school if the need arises.

Even as national immigration policies are thrown into chaos, cities across the United States are working to make sure everyone in the community has equal access to services, education, and opportunity. Governments can do this through proactive leadership, sending a message of inclusivity to constituents. Inclusive and holistic civil society and education initiatives generate more opportunities for individual and family success and boost the overall health of the community. As the United States and Germany become more diverse, practitioners on both sides of the Atlantic can learn from each other’s toolkits to build more prosperous and inclusive societies.