Jorge Royan via Wikimedia Commons

Carbon Management

Felix Schenuit

German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP)

Dr. Felix Schenuit is a research associate in the Research Cluster Climate Policy and Politics at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP) in Berlin. He conducts research on European climate and industrial policy, carbon dioxide removal, and carbon management. He holds a PhD from the University of Hamburg and has been a visiting researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), the International Institute for Applied System Analysis (IIASA), and the Climate and Energy College at the University of Melbourne.

Sonja Thielges

German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP)

Sonja Thielges is a Geoeconomics Non-Resident Fellow. She was a DAAD/AGI Research Fellow from mid-March to mid-May 2019 and explored foreign policy interests in Germany and the United States related to the countries’ energy transitions. In Germany, she is a researcher at the Research Cluster Climate Policy and Politics at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP) in Berlin. Her research interests include climate foreign policy, the global energy transition and industrial decarbonization. Her research has been published in studies, policy papers, online blogs, and academic publications.

Prior to SWP, Sonja was head of the Industrial Decarbonization research group at the Research Institute for Sustainability (RIFS, formerly Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies, IASS) in Potsdam. She was a visiting researcher at the University of Michigan’s Center for Local, State, and Urban Policy in Ann Arbor in 2014 and previously also worked on projects at the Environmental Policy Research Centre (FFU), the Institut für Europäische Politik (IEP) Berlin, and the Centre International de Formation Européenne (CIFE). In 2017/2018, Sonja was a participant in the AGI project “A German-American Dialogue of the Next Generation: Global Responsibility, Joint Engagement,” sponsored by the Transatlantik-Programm der Bundesrepublik Deutschland aus Mitteln des European Recovery Program (ERP) des Bundesministeriums für Wirtschaft und Energie (BMWi). She completed an MA in North American Studies, Political Science, and Modern History at Freie Universität Berlin and Indiana University Bloomington and holds a PhD in political science from Freie Universität Berlin. Her PhD thesis studied climate policy discourses in the U.S. Rust Belt states.

A New Pathway for Transatlantic Cooperation?

In the wake of the proliferation of net-zero emissions targets, a cluster of technologies has witnessed a resurgence in interest. Carbon management, which encompasses carbon capture and storage (CCS), carbon capture and utilization (CCU), and carbon dioxide removal (CDR), has become the subject of a multitude of new policy initiatives in a wide range of countries. Countries differ considerably in how they have addressed these three groups of technologies and how new momentum unfolds in practical climate and industrial policy. Germany—a country with a turbulent CCS debate in the past—and the United States—as one of the pioneering countries on these technologies—are key countries to understand the evolution of approaches and policies toward carbon management. In these times of political turbulence on both sides of the Atlantic, it is particularly interesting to explore routes for potential future transatlantic carbon management cooperation.

Differentiation is key

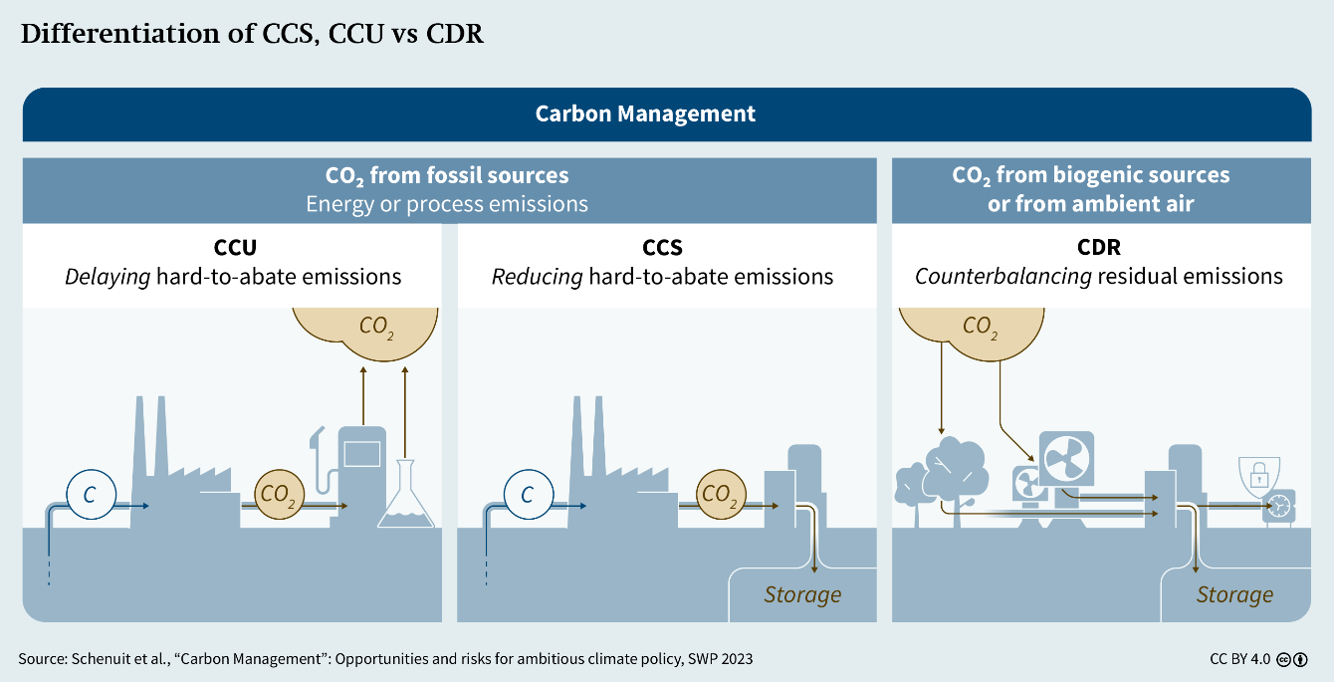

CCS, CCU, and CDR play different strategic roles in mitigation policy. The key distinction is the source of CO2 capture (for an overview of the terminology, see Schenuit, Boettcher, Geden 2023 and Figure 1). If captured from a fossil point source (e.g. cement production) and used in products (e.g. in chemicals), hard-to-abate emissions can be delayed until the end of the product’s life cycle. In addition, using captured CO2 as a feedstock can have substitution effects, reducing the amount of fossil hydrocarbons needed for these processes. If the captured fossil CO2 is permanently stored in underground geological formations or products, the technologies can reduce hard-to-abate emissions. If the CO2 is captured from the atmosphere, e.g. directly from ambient air, the technologies can remove CO2 from the atmosphere and counterbalance residual emissions. The distinction between fossil CCS/CCU and carbon dioxide removal is important because net-zero CO2 or greenhouse gas emission targets require that all residual emissions are counterbalanced. CCS/CCU of fossil CO2 will not be sufficient to achieve this; mitigation policies must therefore also address CDR (see Smith et al. 2024).

All three elements of carbon management will have to go hand in hand to achieve ambitious climate goals. To date, Germany and the United States differ considerably in their approach to carbon management. The following short snapshots of key developments in the countries allow for exploring opportunities for transatlantic cooperation.

Carbon Management in Germany: A CCS Renaissance

Short history

When CCS was first regulated in Germany in the late 2000s and early 2010s, following the adoption of a new CCS regulation at the EU level, the technology faced strong public opposition. At the time, it was mainly discussed as an option to reduce emissions from coal-fired power generation, thereby delaying the phase-out of coal. As a result, the 2012 CCS Act (KSpG) effectively banned CCS in Germany. Since then, not a single storage project has been started in Germany, with the exception of a small-scale pilot research project that ran between 2004 and 2017 (research project in Ketzin, Brandenburg).

However, following the adoption of the net-zero GHG target by 2045 in 2019 in the German Climate Change Act, hard-to-abate emissions in industry were identified as a key issue not yet addressed by existing climate policy. While the government at the time could not agree to initiate reforms and launch a new debate on CCS, the new coalition formed in 2021 between the Social Democrats (SPD), the Greens, and the Free Democrats (FDP) proactively addressed the issue by announcing a carbon management strategy and a reform of the CCS Act.

Recent reforms

What followed was a set of key reforms, most of which are still in the parliamentary process. Three key elements of the proposed reform of the CCS Act include, first, that exploration of offshore storage sites in Germany’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) or continental shelf would be allowed, except for marine protected areas. For onshore storage, the government envisages an opt-in rule, meaning that the sixteen federal states can decide to allow onshore storage in their territory. Second, the proposed amendment to the law and additional decisions would allow multimodal CO2 transport both in Germany and for international export. Given the long lead time for storage projects, every ton of CO2 sequestered in the short-term would have to be exported, e.g., to Norway or Denmark, countries that offer to import the CO2. A third element of the revisions concerns specific applications for CCS and CCU. While applications at coal-fired power stations are banned, those at gas-fired power stations are not—one of the most criticized elements of the law.

Carbon management may remain an area for continued and expanded transatlantic cooperation and is a topic that now enjoys support across most political parties in Germany.

The renaissance of CCS has been critically discussed by organized civil society, revealing a key internal divide: while some recognize the need for CCS in industry to capture process emissions, others are totally opposed. This divide is also reflected in the political parties, particularly the Greens and the Social Democrats. However, the unfolding crisis in German and European industry has made carbon management an issue linked to supporting future competitiveness. Support for CCS, also in a future German government formed after the upcoming snap election, can therefore be expected.

Embeddedness in EU carbon management policy

The latter development has also given a new impetus to carbon management at the EU level. Although CCS has long been discussed more openly at the EU level and in some Member States, the last and the new Commission have identified carbon management as a key bridge between an ambitious climate policy and a new focus on the competitiveness of European industry. One illustration of this new prioritization is the 2024 Net Zero Industry Act (NZIA). This new regulation, which was introduced by policymakers in response to the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) adopted in the United States, established a new “injection capacity target” of 50 Mt per year of CO2 by 2030. This target is to be achieved by companies with hydrocarbon extraction rights.

To date, the amount of carbon capture, and even more so carbon storage, is very limited. Although it is already integrated into the emissions trading system (ETS), i.e., CO2 that is proven to have been captured and stored allows companies to avoid having to issue allowances, very few projects have been implemented given the significant difference between the ETS price (around €70 at the time of writing) and the cost of CCS. However, new funding opportunities for large projects, including several at cement plants, through the EU’s Innovation Fund and support for cross-border transport infrastructure projects through Projects of Common Interest (PCI) or Projects of Mutual Interest (PMI), as well as an announced legislative package on carbon management, indicate that the new Commission intends to bridge this gap and facilitate the up-scaling of technologies toward a European internal market for carbon management.

Carbon Management in the United States: A Bipartisan Approach

Short History

In contrast to Germany, CCS has been promoted by the U.S. federal government for decades. CCS and carbon management more broadly enjoy broad bipartisan support. Most Democrats see it as an opportunity to mitigate emissions. Republicans see it as an energy policy approach: Since the 1970s, the main use of CCS has been in the context of enhanced oil and gas recovery (EOR or EGR) projects. EOR and EGR essentially mean that CO2 is injected into a reservoir to push out oil and gas that could not be recovered by other methods. And while the CO2 that was injected ideally remains captured permanently underground, this technique allows oil and gas producers to recover more of the oil and gas from the reservoirs, which produce more methane and CO2 downstream. The United States currently has fifteen operating CCS facilities and a pipeline network that spans 5,000 miles. 121 facilities are under construction or in development. Texas has the highest number of operating CCS facilities with a total capture capacity of 7.8 million tons of CO2. With only two operating projects, Wyoming has the highest capture capacities at 7.9 million metric tons of CO2. Almost all of the operating facilities use the captured CO2 for EOR. Republicans have also embraced carbon management as a means to promote public acceptance of fossil fuels, citing “carbon sequestration initiatives” as an incentive for people to buy electricity from coal- or gas-fired power plants.

Regulation and recent reforms

In the United States, the general incentive structure for CCS is different than in Germany and the EU. There is no price on carbon at the federal level that puts pressure on industries to reduce emissions. In addition, the U.S. carbon neutrality target for 2050 was set by the Biden administration by executive order. It therefore lacks permanency, and it will come as no surprise if the new Trump administration no longer pursues it. Some states, including California and Nevada, have, however, set their own legally binding net-zero climate targets which provide an incentive structure for carbon management.

CCS and CCU and, more recently, CDR, have, nevertheless, received major support under the “45Q” tax credit. It was first enacted as part of the U.S. tax code in 2008. Between 2010 and 2019, companies claimed $1 billion of credits under 45q. In 2018, the Bipartisan Budget Act broadened the eligibility of 45q. In 2020, then-president Donald Trump signed into law a bipartisan carbon capture bill, the Utilizing Significant Emissions with Innovative Technologies (“USE IT”) Act. It extended the 45Q tax credit for two years, supported CCU and DAC research, and sped up permitting processes for CCU/CCS projects and CO2 pipelines. Carbon management received a significant additional boost through the IRA, which further expanded 45Q. When first enacted in 2008, 45Q provided a $10/tCO2 credit for CO2 stored via EOR and $20 for storage in geological formations. Through the IRA, it now provides $180 per ton of carbon captured through DAC and stored in geological formations, $85 for fossil CCS, $130 per ton of carbon captured through DAC and utilized, and $60 for fossil CCU.

Sharing best practices on the challenges of transporting CO2 and building injection capacity, increasing capture rates—including potential export interests—could be one of the few areas where transatlantic cooperation remains possible.

Executive regulations have provided an additional incentive for CCS. The Biden administration in 2024 finalized regulation that requires coal- and natural gas-fired power plants to reduce their emissions by up to 90 percent by 2032. CCS would be required to meet the emission standard. Whether this regulation remains in place under a new Trump administration is unclear. The Biden administration further created the Office of Carbon Management in the Department of Energy, putting the topic much more into focus than under previous administrations.

The federal government has further supported CCS research and programs through its annual budget. The total funding is estimated at $5.3 billion over the course of the period from 2011-2023. Recently, CCS has attracted significant amounts of additional funding through The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (2009, 3.4 billion, not all of it was spent) and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (2021, 8.2 billion between 2022-2026).

At the international level, the Biden administration launched the so-called Carbon Management Challenge at the Major Economies Forum on Energy and Climate in 2023. The initiative aimed to push participants to increase ambition on CCS, CCU, and CDR to advance the decarbonization of the industrial sector.

CCS at the state level

Much of the promotion for carbon management has so far come from the federal level. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is generally in charge of permitting CCS projects. In an attempt to speed up the environmental review process for CCS projects, the EPA has allowed three states (Louisiana, North Dakota, and Wyoming) to review storage site applications themselves. The federal government and the state governments share regulatory authority for pipeline systems. They cooperate with standards-developing organizations to enhance pipeline safety.

Implications for Transatlantic Cooperation

With Donald Trump as U.S. president-elect and both houses of Congress under Republican leadership as of 2025, U.S. interest in climate policy at the federal level can be expected to be minimal. This will significantly reduce formats and topics for transatlantic cooperation on climate-related topics. It will, however, be crucial for Germany and the EU to keep the second-biggest emitter of greenhouse gas emissions engaged in dialogue in different formats at the international level. Carbon management may remain an area for continued and expanded cooperation and is a topic that now enjoys support across most political parties in Germany. As a group of technologies, ranging from well-known technologies such as CO2 injection for enhanced oil and gas recovery to novel methods such as direct air capture, they provide a platform for synergies, even if policy objectives may differ significantly.

Exchanges on carbon management to address hard-to-abate and residual emissions are unlikely to interest the new U.S. administration. But sharing best practices on the challenges of transporting CO2 and building injection capacity, increasing capture rates—including potential export interests—could be one of the few areas where transatlantic cooperation remains possible. The creation of a new forum for transatlantic dialogue on carbon management—bringing together businesses, government, and organized civil society—could help initiate new and strengthen existing cooperation on carbon management. The Clean Energy Ministerial Working Group on CCUS is an existing intergovernmental venue to advance dialogue on key aspects of carbon management. Carbon management might further be an avenue for keeping the new U.S. administration engaged on climate-related topics in plurilateral forums like G7 and G20 as well as bilateral exchanges.

Finally, creating new collaborative research support such as funding for joint research centers that focus on carbon management, would be worth pursuing. In addition to transatlantic cooperation, this could provide opportunities to advance the technologies and bring down their costs, which in turn could be a major contribution to global climate efforts.