Afoxens via Wikimedia Commons

The 2023 Bavarian State Election in Historical Context

Eric Langenbacher

Senior Fellow; Director, Society, Culture & Politics Program

Dr. Eric Langenbacher is a Senior Fellow and Director of the Society, Culture & Politics Program at AICGS.

Dr. Langenbacher studied in Canada before completing his PhD in Georgetown University’s Government Department in 2002. His research interests include collective memory, political culture, and electoral politics in Germany and Europe. Recent publications include the edited volumes Twilight of the Merkel Era: Power and Politics in Germany after the 2017 Bundestag Election (2019), The Merkel Republic: The 2013 Bundestag Election and its Consequences (2015), Dynamics of Memory and Identity in Contemporary Europe (co-edited with Ruth Wittlinger and Bill Niven, 2013), Power and the Past: Collective Memory and International Relations (co-edited with Yossi Shain, 2010), and From the Bonn to the Berlin Republic: Germany at the Twentieth Anniversary of Unification (co-edited with Jeffrey J. Anderson, 2010). With David Conradt, he is also the author of The German Polity, 10th and 11th edition (2013, 2017).

Dr. Langenbacher remains affiliated with Georgetown University as Teaching Professor and Director of the Honors Program in the Department of Government. He has also taught at George Washington University, Washington College, The University of Navarre, and the Universidad Nacional de General San Martin in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and has given talks across the world. He was selected Faculty Member of the Year by the School of Foreign Service in 2009 and was awarded a Fulbright grant in 1999-2000 and the Hopper Memorial Fellowship at Georgetown in 2000-2001. Since 2005, he has also been Managing Editor of German Politics and Society, which is housed in Georgetown’s BMW Center for German and European Studies. Dr. Langenbacher has also planned and run dozens of short programs for groups from abroad, as well as for the U.S. Departments of State and Defense on a variety of topics pertaining to American and comparative politics, business, culture, and public policy.

__

As the federal state with both the second-largest population (13.4 million, 16 percent of the country’s total) and economy (18.5 percent of the country’s total), what happens in Bavaria matters. On October 8, Bavarian voters will go to the polls to elect their 19th parliament (Landtag) of the postwar period. According to a recent poll, the ruling Christian Social Union (CSU) under their dominant leader and minister-president Markus Söder come in at 40 percent, the Greens at 15 percent, the Alternative for Germany (AfD) at 13 percent, Free Voters (in the current coalition government) at 12 percent, the Social Democrats (SPD) 9 percent, Free Democrats (the Liberals, FDP) 4 percent and Left 2 percent. In light of the 5 percent electoral threshold required for parties entering parliament, if things do not change, both the Liberals and Left will not gain representation in the parliament, and a continuation of the current CSU-Free Voters government is a likely outcome. Therefore, this might not be a super dramatic election, but rather a vote for continuity and the status quo.

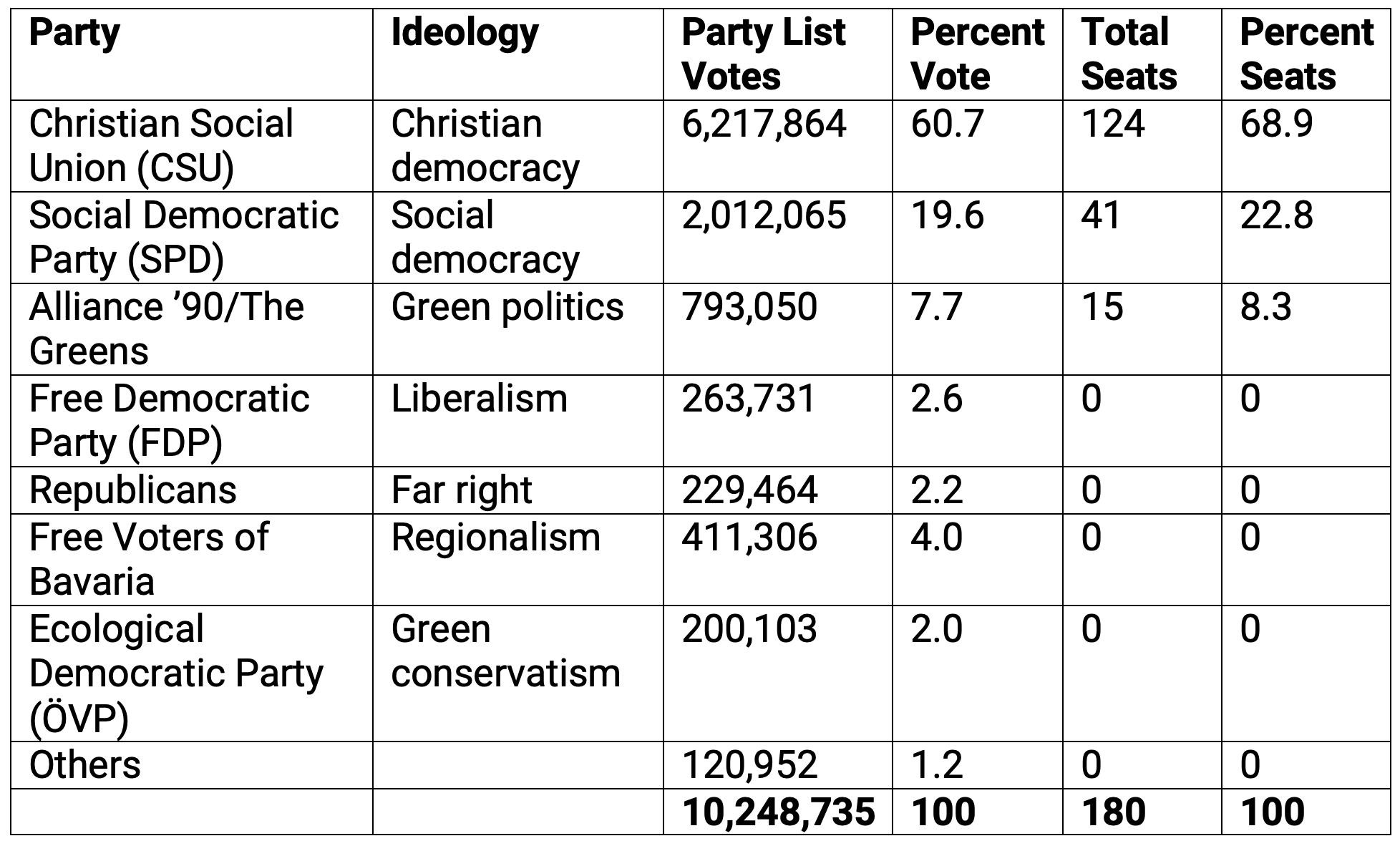

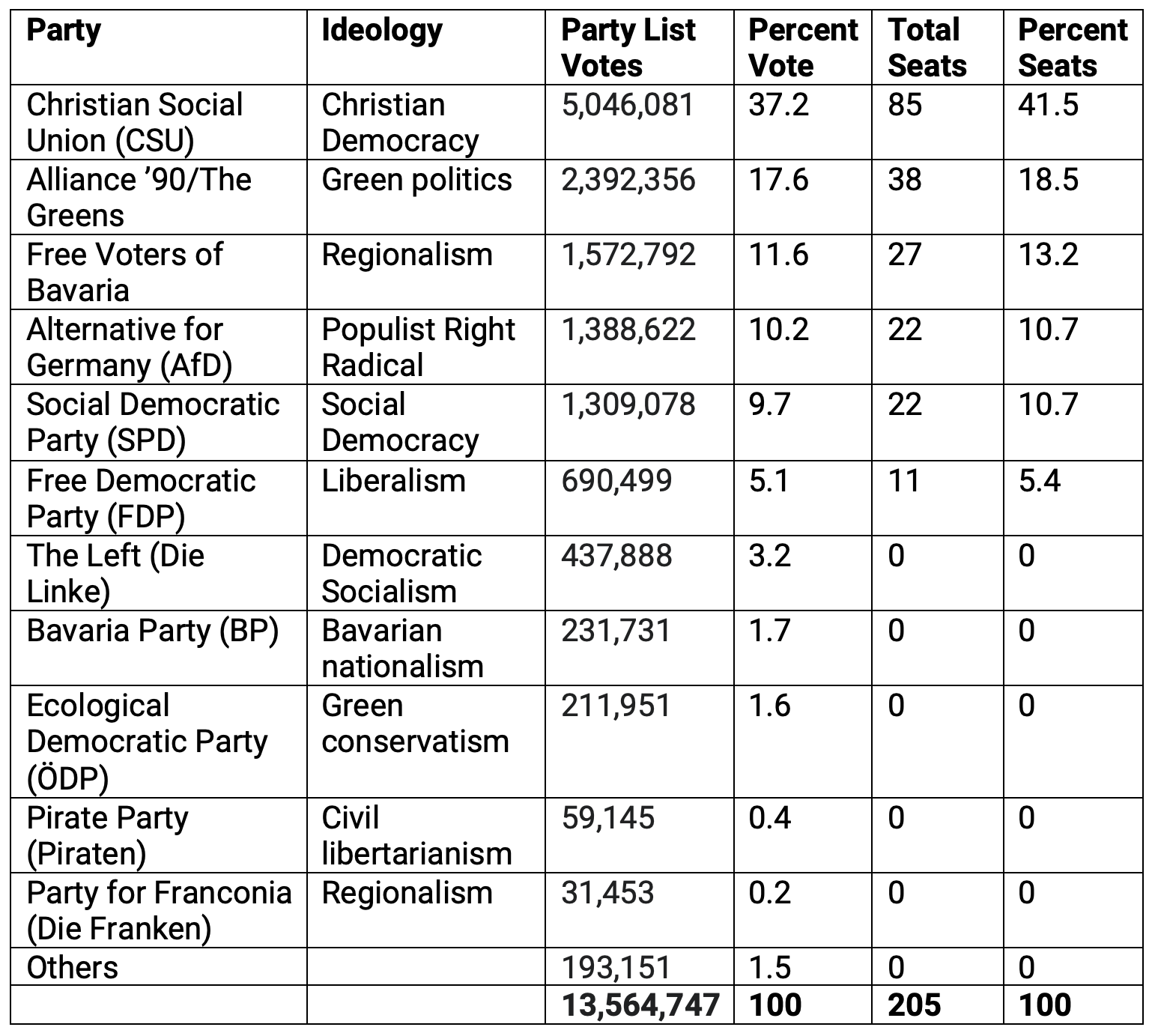

Be that as it may, it is fascinating to take a look back at how much has actually changed in Bavaria over the last twenty years by comparing the last election in 2018 to the election of 2003. I have included a couple of calculations: the effective number of parties based on seats and votes (weighting parties by their strength) and proportionality to see how well the electoral system translates votes into seats. (More technical details are available upon request.) Here are the results:

2003

2018

In 2003, the effective number of parties based on votes was 2.40 and 1.87 based on seats. The percent reduction in effective parties was 22.08 percent, which is higher (i.e., more disproportional) than the long-term international baseline of 16.5 percent. The score of 1.87 indicates that Bavaria was a two-party system, tending towards one-party dominance. In fact, for decades the state was dominated by the CSU (which only runs in Bavaria, but is perpetually allied with the Christian Democrats at the national level) and could be considered a hegemonic one-party democratic system. Indeed, it has led every government since 1946 (except 1954-57) and ruled alone from 1966-2008 and 2013-2018.

In 2018, the effective number of parties based on votes had risen to 4.83 and 4.01 based on seats. The percent reduction in effective parties was very close to the global baseline at 16.98 percent. Both of these scores put Bavaria clearly in the moderate multiparty category of party systems. Between these two elections, the CSU’s share of the vote was reduced about 25 points from nearly 61 percent to 37 percent. More contingent factors, such as dissatisfaction with the national government (of which the CSU was a coalition partner) or that Söder was relatively new (becoming minister-president in March 2018 with the election in October), partially explain this decline. But Bavarians’ preferences are much more diverse and pluralistic than before. Indeed, in addition to adding about a million people over this timeframe, the proportion of Bavarians with a migration background went from about 18 to over 21 percent.

Other noteworthy trends include the rise of the Greens, doubling their share of the vote. They are now much more of an acceptable “bourgeois” party, even having run the next-door state of Baden-Württemberg in coalition with the CDU since 2011. They have supplanted the SPD as the main center-left alternative. Indeed, the SPD’s support was halved between 2003 and 2018, and they have not recovered by 2023. Equally as striking is the rise of the Free Voters (Freie Wähler), considered a center-right localist party and, as elsewhere in Germany, the populist right-radical Alternative for Germany (AfD). It is clear that voters for these parties have moved away from the CSU. Given their institutionalization by this point in time, they are likely to remain a set part of the party spectrum going forward.

The results in October will likely mirror those of 2018. But, the contrast to twenty years ago is striking. The era of almost absolute CSU dominance is in the past. Political preferences are much more diverse and the corresponding party system has expanded and is more competitive. Governance will be more challenging and campaigns will matter more because Bavarian voters have options, and no party can take votes for granted.