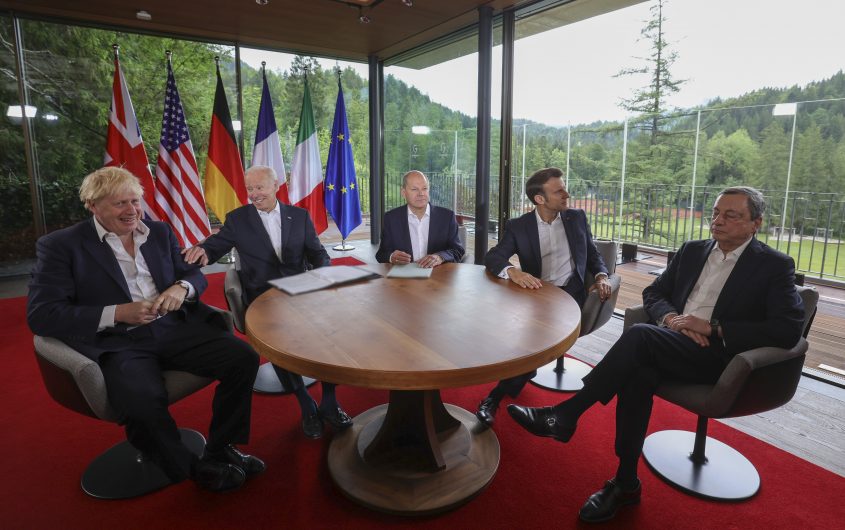

Andrew Parsons / No 10 via Flickr

The Transatlantic Balance We Love to Hate

John Kornblum

AGI Trustee

John Kornblum is a senior counselor at the international law firm Noerr LLP and a former U.S. ambassador to Germany. He is a member of the AGI Board of Trustees.

European discovery and settlement of the New World is one of the great sagas of human history. The two continents of the Western Hemisphere were torn from their traditional existence to feed into a “new world” built by the nations of Europe. Cultures and societies of the native peoples were either destroyed or changed beyond recognition. This great Atlantic community was the product of European expansion. It has survived for more than 400 years.

But living together has always been difficult for these two branches of Western civilization. Differences in size and power, jealousy, and perhaps above all debates over the right road to take have burdened ties between the old and new worlds from the very beginning. Now once again this Western world is changing dramatically, probably forever. The continued health of the vibrant community we have built over the last four centuries requires a new set of guideposts for the future.

We can perhaps be helped by some basic facts. The United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand are unique in that they are Europe-based societies built far from Europe’s boundaries. Their dominant history, culture, and philosophy are the ones carried by Europeans.

Thus, there are no alternative futures for the West, let alone Australasia. As the legendary American commentator Walter Lippmann put it, the Atlantic basin is an organic community which no one can enter and from which no one can be expelled. As a result, the cultural and economic boundaries which define our various identities are indigenous. They have never run through the middle of the Atlantic. And they cannot be erased.

America has become the most important European power, the one which keeps the European and Atlantic balance operating.

At the same time, by establishing images of themselves across the Atlantic and Pacific, Europeans were also changed permanently by the influences from the New World. Many of Britain’s great manors were built by fortunes earned in the slave trade to North America, for example.

This reciprocal fertilization of Europeans and their American offspring has defined their joint existence for nearly five hundred years. We are one cultural and social entity which harbors dozens of different identities. But we are also fundamentally different in many ways.

The catastrophic results of World War II led to a fundamental change in the Western center of gravity. The United States inherited Europe’s power and global mission. Europe’s burdens of empire led to a retreat from the global vision of the early explorers, and post-war European states began to define their futures within the geographic and organizational boundaries of Europe, even as their interests reached far beyond it. Europe’s political collapse created a new reality for both sides of the Atlantic. That the United States was now the senior partner was neither normal nor satisfying on either side of the Atlantic.

But seventy-five years later, European dependence on the United States has grown even more. Once again, the United States is called upon to solve deep European conflicts which have erupted into war. Europeans are grateful for this support, but also fearful and angry. Once again, there are calls for an alternative European narrative. My approach to this situation has evolved over the years into recognition that, especially when the distribution of power becomes so one-sided, mutual disrespect is part of the interplay between two competing versions of the same culture.

The United States is much more than a partner or ally. Our commitment to the security and prosperity of Europe after 1945, and our achievement in bringing about the end of the Cold War has made the United States a permanent and necessary fixture of the European structure.

This tension can add energy to the relationship, and we should not be too worried about it. Most important is not to take seriously repeated American efforts to overcome it—especially with France—or European visions of attaching themselves somewhere else, combined with corresponding European efforts to become “emancipated.” This won’t work.

As the late, eminent German sociologist Ulrich Beck wrote in 2003: “The birth of the non-belligerent Europe after World War II… [was] made possible by the organizing power and the continental presence of America. … The historic amalgamation of the Atlantic Community, EU, and NATO…becomes especially important at this historical moment when it is threatening to fall apart. The extent to which a merely European Europe… is possible is highly questionable.”

In other words, America has become the most important European power, the one which keeps the European and Atlantic balance operating. Assistant Secretary of State Richard Holbrooke described the situation as follows in 1995: “This…underlines an inescapable but little-realized fact: the United States has become a European power in a sense that goes beyond traditional assertions of America’s ‘commitment’ to Europe.”

Holbrooke continued, “In the 21st century, Europe will still need the active American involvement that has been a necessary component of the continental balance for half a century. Conversely, an unstable Europe would still threaten essential national security interests of the United States. This is as true after as it was during the Cold War.”

In other words, this is a permanent situation. The United States is much more than a partner or ally. Our commitment to the security and prosperity of Europe after 1945, and our achievement in bringing about the end of the Cold War has made the United States a permanent and necessary fixture of the European structure. This is a situation which is not always comfortable for the United States, nor is it always comfortable for the proud nations of Europe to be dependent on their offspring for survival. As the anchor power of Europe, American self-interest will dictate that this active presence is permanent. But as Robert Kagan recently put it, “Americans don’t do world order.”

We usually need a crisis to keep us engaged. It has arrived, in Ukraine. But even that tragedy cannot be the permanent foundation of a future Atlantic narrative. An even larger upheaval, fueled by digital technology and climate change lies ahead. Time to break through the walls of the past. Without our Atlantic Community, there can be no global peace.