Mietek, Mina, and Mark. (Photo courtesy of Rebecca Ostoyich)

The Entertainer: Mark Newton’s Raison d’être

Kevin Ostoyich

Valparaiso University

Prof. Kevin Ostoyich was a Visiting Fellow at AICGS in summer 2018 and was previously a Visiting Fellow at AICGS in summer 2017. He is Professor of History at Valparaiso University, where he served as the chair of the history department from 2015 to 2019. He holds his B.A. from the University of Pennsylvania and his A.M. and Ph.D. from Harvard University. Prior to moving to Valparaiso, he taught at the University of Montana. He has served as a Research Associate at the Harvard Business School and an Erasmus Fellow at the University of Notre Dame. He currently is an associate of the Center for East Asian Studies of the University of Chicago, a board member of the Sino-Judaic Institute, and an inaugural member of the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum International Advisory Board. He has published on German migration, German-American history, and the history of the Shanghai Jews.

While at AICGS, Prof. Ostoyich conducted research on his project, “The Wounds of History, the Wounds of Today: The Shanghai Jews and the Morality of Refugee Crises.” The Shanghai Jews were refugees from Nazi Europe who found haven in Shanghai, and thus escaped the Holocaust. For this project Ostoyich has interviewed many former Shanghai Jewish refugees and has conducted research at the National Archives at College Park, MD, and United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. At Valparaiso University he co-teaches a course titled “Historical Theatre: The Shanghai Jews,” which fuses the disciplines of history and theatre. To date, students of the course have co-written and performed two original productions based on the history of the Shanghai Jewish refugee community: Knocking on the Doors of History: The Shanghai Jews and Shanghai Carousel: What Tomorrow Will Be. In addition to his work on the Shanghai Jews, he is currently working on projects pertaining to the experiences of ordinary Germans during the bombing of Bremen, German Catholic experiences in nineteenth-century Württemberg, German Catholic migration, and U.S.-German cultural diplomacy during the first half of the twentieth century.

Click here for an article by Ostoyich on the Shanghai Jews.

He is currently trying to interview as many former Shanghailanders as possible. If you would like to be interviewed or know someone who might want to be interviewed, please contact Professor Ostoyich at kevin.ostoyich@valpo.edu.

When the door opens at Mark Newton’s condominium in Yardley, Pennsylvania, it is as if a curtain has been drawn back from the stage. One is immediately met with movie posters and theatre playbills. As Mark guides you around, questions start to present themselves in abundance: Why is there a huge portrait of Queen Victoria in the guest bedroom? What is wrong with her head? And why is there a photograph of Mickey Mantle next to the Queen? And what about the Master of Ceremonies himself: Why is Mark wearing a t-shirt with FINLAND printed on it in large letters? And why, when he rolls up the right sleeve of the t-shirt, does a tattoo of the words YOUR MAMA appear? If, while taking all of this in, one has not remarked on all the items devoted to the film Cinema Paradiso, Mark makes sure they are noted. He lets you know immediately that the Italian film is close to his heart. He does not tell you exactly how or why; however, for that is for you to find out along the way as he regales you with stories, jokes, and a card trick or two.

Who is this man? What makes him tick? Does Cinema Paradiso really provide the key? Sure enough, as one reflects on all the odds and ends, they start turning into snippets of film. By splicing them together and projecting them onto the screen, a raison d’être appears before our eyes in montage: Mark Newton is an entertainer—and he learned his craft from Polish parents who fled from the Nazis.

YOUR MAMA

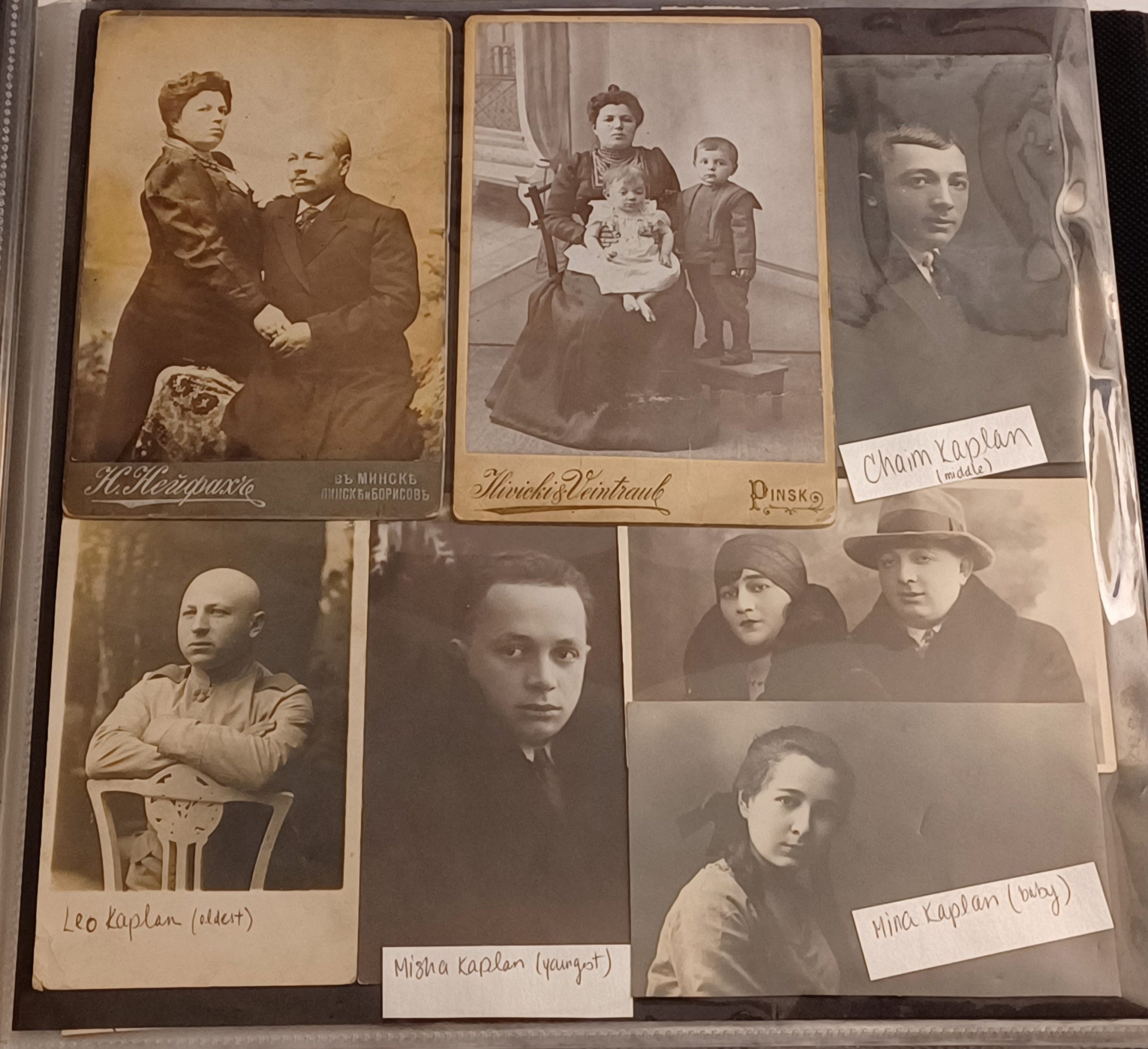

Mina Kaplan was an entertainer.[1] She grew up in Pinsk, attended a music conservatory, studied the piano, and sang Yiddish songs. She was the youngest and only girl of four children in the wealthy family of Mottel (Mordcha) and Rachela (née Lipszyc) Kaplan. Mottel built ships and owned apple orchards. He knew Syzja Nowomiast, a wealthy landlord in Warsaw, and the Kaplan and Nowomiast families were friendly. Syzja and his wife, Chawa (née Cwajbaum), had three sons: Mojzesz/Mieczyslaw, Stanislaw, and Maksymilian. The families felt that the oldest of the Nowomiast sons, Mojzesz, who was born in 1904 and was known by his nickname, Mietek, was a good match for Mina. Mietek had been educated at the University of Nancy and the University of Antwerp and was a businessman. Mietek was a stereotypical rich man’s oldest son: He was used to luxury and getting his way. He did what he wanted. Mietek ran a motorcycle store with his youngest brother, Stanislaw. Maksimilian—the middle brother—most likely did not have much to do with the business. Maksimilian was always described to Mark as being a poet and someone who “went to the beat of his own drum.” Mietek was the clear driving force behind the motorcycle store, and Mark always got the impression that the business was “very much a rich man’s business that was more like a hobby than a need to generate revenue.”

Mietek and Mina were married in 1933 and lived in one of Syzja’s houses in Warsaw. Mina gave up her musical studies at the conservatory. Mietek continued to run the motorcycle store in the city. Mark knows that his father tended to sell motorcycles from Germany. From old photographs from Warsaw, Mark knows that his father drove a motorcycle with a sidecar. He also remembers being told that his mother often rode in the sidecar. Mietek and Mina lived a life of luxury in Warsaw with servants, a chauffeur, and the like. Mina did not work and spent much of her days meeting up with other ladies in cafés. Mark says that his parents “enjoyed six years of bliss in Warsaw,” but then their lives were upended with the German invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939. Mietek—knowing immediately that they needed to get away—decided that he and Mina should leave the city at once. Along with Mietek’s brother Stanislaw and Stanislaw’s wife Mina, Mietek and Mina journeyed to Pinsk and lived in the countryside on a property owned by Mina’s father, Mottel Kaplan. Thus, they were gone from Warsaw by the time the city was occupied by the Germans in late September 1939.

Mark explains what happened next for Mietek, Mina, Stanislaw, and Mina: “They couldn’t stay there [in Pinsk] either. It was really too close. So, they made their way to Vilna (Vilnius today), Lithuania.” Mark does not know how the four made ends meet while they were in Vilna. He thinks that perhaps any jewelry they had managed to bring with them from Poland may have come in helpful in this regard. He thinks his father may also have sold watches. But more than this he really does not know. He thinks they were in Vilna for approximately a year: “Then things started to get heavy in Lithuania, and that is when it became a crusade to get out of Lithuania before it was too late. So, they were part of a number of Jewish people who went to Kaunas, Lithuania, and were begging in front of the Japanese consulate for a man who was the [vice-] consul from Japan named Sugihara. A big hero. [Mark starts to cry.] I get emotional when I think about that. That one man can have such an effect on the lives of at least 3,000 people. And he provided, as many as he could, transit visas.”

The man behind Mark’s tears was Chiune Sugihara. This Japanese man helped save the lives of Mietek, Mina, Stanislaw, Mina, and a few thousand other Jewish refugees. The Jews required transit visas to travel from Kaunas. Seeing the desperate plight of the Jewish refugees in the city that was under Soviet occupation, Sugihara issued thousands of transit visas from the Japanese consulate. In addition to a transit visa, the refugees needed a destination. The destination of Curaçao was provided by Jan Zwartendijk of the Dutch consulate. It did not matter that the refugees had no intention of going to Curaçao. With the Japanese travel visa and the Dutch “destination,” the refugees could travel through the Soviet Union and get to Japan. Both Sugihara and Zwartendijk have been officially recognized as “Righteous Among the Nations” by Israel. This high honor is bestowed to those non-Jews who assisted Jews for no material gain to themselves. On August 7, 1940, Mietek, Mina, Stanislaw, and Mina were issued Sugihara Visas 1380, 1381, 1382, and 1378, respectively.[2]

With their Sugihara transit visas and their Curaçao “destinations,” Mietek, Mina, Stanislaw, and Mina went through the Soviet Union on the Trans-Siberian railroad with all of their possessions. They then took a boat to Japan. Eventually, they went from Kobe, Japan, to Shanghai. In Shanghai, they got off the boat and stayed, for the simple fact—and yet highly unique at the time—that they could do so without an entry visa.

In Shanghai Mietek, Mina, Stanislaw, and Mina lived together in a one-room apartment and did what they needed to survive. Unfortunately, Mark does not know much about what his parents and aunt and uncle did in Shanghai but knows it would not have been a pleasant time, especially given that Mietek and his sister-in-law, Mina, did not get along well. Mark explains that his father was a natural leader and was used to getting his way. He also had a tendency of reminding the other three that he had saved their lives. Mark thinks that both his father and uncle may have worked for the United States military at some point, perhaps for the 4th Marines who were stationed in Shanghai until November 1941 or much later when the Americans entered Shanghai at the conclusion of the Second World War.

On February 9, 1944, Mina gave birth to Mark. Although he was formally given the name Marjan, his family called him Marek. Mark would be Mina and Mietek’s only child. Mark says that he was really the only child for two sets of parents in Shanghai: Mietek and Mina and his Uncle Stanislaw and Aunt Mina. Mark’s first memories of Shanghai are of fear—fear of the disabled Chinese in the streets. He does not remember much else about Shanghai, but he does remember that he attended kindergarten and that he grew up speaking multiple languages.

In Shanghai Mark had an amah. He says the woman helped his mother not only with tending to him but also with housework. He says he does not know if his mother had to go out to work while they lived in Shanghai, but he does remember that she did do a lot of knitting to make extra money for the family.

After the war, the scramble was on to leave Shanghai. The question was where the Jewish refugees would be accepted. Given that Mietek, Mina, Uncle Stanislaw, and Aunt Mina were from Poland, the prospects of going to the United States were not good. United States immigration policy was still based on the restrictive quotas that had been so prohibitive to visa applicants prior to and during the Second World War, and the Polish quota was one of the lowest. A relative in Brazil agreed to sponsor Uncle Stanislaw and Aunt Mina, and they left Shanghai for Rio de Janeiro in 1947.

Mietek, Mina, and Mark had to continue their wait to get out of Shanghai. Mietek applied for visas to the United States, but when he put down “Stanislaus Nowomiast” as his brother on the application, eyebrows were raised among the consular officials. These officials wondered if this could be the same as one “Stanislaff Novomiast” whom they believed had participated in the Pan-Slavic movements in Shanghai. This was deemed problematic, because they thought this movement “had connections with the Soviets and later attempted to unite itself with the Yugoslavian Group and Czech Group.”[3]

Given the suspicion with respect to Stanislaw, Mietek was interviewed by Vice-Consul Norman B. Hannah. Hannah wanted to know exactly what Mietek knew about the various Polish organizations in Shanghai. Notes dating from August of 1948 in the declassified files reveal that the officials did not believe they really had anything to keep the Nowomiast family from coming to the United States. Unfortunately, not everything in the Nowomiast file has been declassified, so the full story of their visa application cannot be told at this time. Whatever the circumstances may have been, in 1949, Mietek, Mina, and Mark were permitted to board the S.S. General M. C. Meigs for San Francisco. The plan was not to stay in the United States, however. Mark explains,

My parents had a visa out of Shanghai to go to Paraguay, and the plan was that my mother had an aunt in Buenos Aires. And they had arranged that if we got to Paraguay, the aunt in Buenos Aires would come and get us and bring us to Argentina. And that was the plan, except, when we landed in San Francisco, my mother also had an uncle who lived in New York City. And he came to California and filled out some paperwork or pulled some strings, whatever, and, instead of us continuing on to go to Paraguay, he found a way for us to stay in the United States.

Rather than Buenos Aires, the family set out for Manhattan. They moved into a one-room apartment on 106th Street at West End Avenue.

Mietek started to use the Anglicized name of Marvin and once again turned to German motorcycles. He set up an office for General Merchandise Co. at 170 5th Avenue. He rekindled his relationship with Triumph-Werke Nürnberg. This had been a German branch of the famous British company that manufactured Triumph motorcycles in Coventry, England. The German branch became independent in 1929, but production of motorcycles ceased there in 1957.[4] Marvin eventually opened the motorcycle store on 172nd Street and moved the family to 148th Street in Harlem so he could live closer to the store. Mark sums up his father’s motorcycle business by invoking the late comedian Jackie Mason who said that any Jewish businessman will say that he would have been a millionaire if it hadn’t been for his partner. Mark says that his father was one of those who had a series of business partners, who, according to him, were dumb, stupid, and were the cause of his lack of success.

Marvin had not discussed the decision to move to Harlem with Mina. Mark explains this was typical for his father—the eldest son of the wealthy family in Warsaw who always got his way and who continued to use the line that Mina could not complain about his decisions because he had saved her life on three occasions. Mark explains that those were different times and men tended to make such decisions, and his father was not going to be told what to do by anyone.

Another thing about Marvin’s personality was that he was naturally funny. Not because he told jokes—Mark does not remember his father ever telling a joke—but more that the things he did and said were just funny. When it came to jokes, it was Mina who loved to tell the zingers.

Mina told jokes all the time. Mark explains that even when he was a teenager, “she would say, ‘Mark, I’m running out of jokes, do you have any new ones?’ She liked to tell filthy jokes! Here’s this little, tiny Jewish woman, who looked like a typical Eastern European Jewish woman, maybe 5 feet tall, big-breasted, dark hair, and so on, and she would tell filthy jokes. And the old refugees loved it. They loved them! She was bold and out there and not shy! And that’s what I inherited.”

But Mina was not only telling jokes in Manhattan; she also sang.

She sang all the standard Yiddish songs. Oyfn Pripetchik was one. And some lullabies—I can’t remember the names of all of them. But I remember a lot of the words, and we would sing them together. And she had songbooks full of them. And all of the old Jews sitting in the room would start crying when they heard the song. Yiddische Mama was a famous song that all of the Jews knew—I don’t know if you’ve heard of it, but it’s a song about what it means to have a Jewish mother, and it’s tear-provoking beyond belief. So those two songs I remember distinctly. So, she got to perform for her friends.

Mark notes that it is not particularly “Kosher” for Jews to have tattoos given the painful legacy of the Holocaust, but he has two tattoos on his right arm: One is the famous logo of the New York Yankees. For someone who grew up in New York City in the 1950s, this needs no explanation. The other, a heart with the words “Your Mama,” definitely does:

“Your Mama” is an expression that I learned in Junior High School in Harlem. “Your Mama” is what everybody said to everybody else. No matter what. It was like an epithet or greeting, almost. It was almost like a hello. “Your Mama,” like that. And everybody knows about mama jokes and so on. So, that’s so much a part of my life, I put it here. So, when [the theater company I performed with did a roast of me], someone came and imitated my mother, and explained how all of that happened and “Your Mama this, your mama that!” And then my daughter got up on the dais, [when] it was her turn, and she brought the house down, she said, “All of you who know my dad, know that he is always saying, [pointing around the room] “Your mama, your mama, I did your mama, I did your mama, and so on.” She said, “Imagine how I feel. I’m the only one for whom that’s really true!” [Mark laughs]. The house came down with how clever she was with that!

Mina passed away at sixty-six in 1973. Mark remembers asking his mother when she was near death if she believed in God. Her reply: “I really did. I wanted to believe and believed. But after the Holocaust, how can anyone believe anything.” Mark said he will never forget that she said that. This very much sums up the family’s relationship to religion. Mark explains that they observed the traditional holidays such as Passover and Hanukkah, but very much to commemorate their Jewish culture rather than religious sentiment.

Mina Newton—the diminutive Jewish woman from Pinsk and lover of a good dirty joke—was more angelic than religious. Mark glows as he says, “She was the most angelic soul that I could ever imagine.” In this sentiment, both father and son were agreed. Marvin often said of Mina—who had fled with him from Warsaw to Pinsk; from Pinsk to Vilna; from Vilna to Kaunas; from Kaunas through the Soviet Union then on to Japan; from Kobe, Japan to Shanghai, China; and then spent twenty-four years together in New York City: “She was the soul of every gathering.”

The Mick

Mark attended elementary school at P.S. 179 on 102nd Street. He remembers wearing dog tags that identified him as a displaced person: “We had a dog tag that had our name—and my name was still Nowomiast at the time—and it said “Displaced Person”…and I think we were instructed to wear them…I don’t recall my parents having them, but I had one, and I was supposed to wear it.” Mark says he wore it around his neck and remembers wearing it while attending school. He says when he started attending school in New York City he was placed in the first grade. He thinks maybe he wore it during the first and second grades but maybe did not have to wear it after that (perhaps until 1950 or 1951). He says he does not remember any stigma or feeling ashamed or anything. If he showed friends at school, they probably did not understand what “Displaced Person” meant. He and his parents became citizens of the United States of America in 1954. They changed their surname to “Newton” given that Nowomiast means “new town” in Polish.

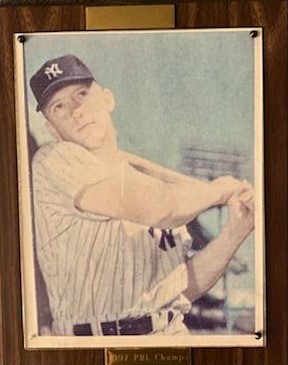

As a kid growing up in New York City in the 1950s, Mark had his pick of wonderful baseball teams—as he thinks back, he instantly starts to sing the refrain from Terry Cashman’s famous baseball anthem, “Talkin’ Baseball (Willie, Mickey, and “The Duke”)” referring to Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle, and Duke Snider—three outstanding centerfielders for the New York Giants, the New York Yankees, and the Brooklyn Dodgers, respectively, and eventual Hall-of-Famers all three—and for Mark, Mickey Mantle was his centerfielder. He remembers listening to a game announcer report that the Yankees farm system had two big prospects: Gil MacDougal and a kid from Oklahoma named Mickey Mantle. As Mark thinks back, he says, “Mickey Mantle—what a name!” Even today, Mark has a photo of “The Mick” hanging in his guest bedroom in Yardley, PA.

But there is more to Mickey Mantle and the New York Yankees than baseball for Mark. For him, baseball meant moving from dog tags to acceptance. Integrating into the school was difficult for Mark, but he found that sports became a valuable asset in this regard. Moving to Harlem posed a challenge to the young Mark. He was now a white kid trying to fit in as an American in a predominantly African-American area. He commuted each day in order to continue school at P.S. 179. In elementary school he was a good student—which he attributes to his infatuation with his teacher, Mrs. Sugar, whom he had for fourth, fifth, and sixth grades. Mark says he would have done anything for Mrs. Sugar, even lick the ground on which she walked! Moreover, he was a good athlete.

Things were not so sweet for Mark in junior high. With the transition to junior high, Mark started to attend school in Harlem. Not only was he a minority in the school, but he also did not grow as much as the other kids, and he no longer had Mrs. Sugar to motivate him scholastically. He started to get shaken down for lunch money and threatened by bullies. Things got so bad that Mina wrote a note to Edward W. Stitt Junior High School explaining that Mark needed to leave school early in order to go to Hebrew School. With such a head-start and an escape route through the girls’ exit, Mark dodged the bullies.

Whereas Hebrew School was a convenient excuse to get out of Stitt relatively unscathed, it did not infuse Mark with much religious feeling. Although he completed his Bar Mitzvah, he did so without much religious fervor. Rather, his favorite part of Hebrew School education was the opportunity it gave him to perform: “I became a star in the childhood productions, of the pharaoh in Egypt and all of the other stories like Seven Golden Buttons, Yiddish humor, and stories. And I never forgot that part of my life, and it came back to me much later.”

Mark has a photograph of Mickey Mantle hanging in his guest bedroom today, and it reminds him of his days as a New York City street kid who adored Mrs. Sugar, played softball in the school gymnasium, and learned the name of every shortstop in the major leagues. He chokes up when recalling that when he and his choral group sang the National Anthem at the Philadelphia Phillies’ Veterans Stadium on August 13, 1995, the announcer came on the p.a. system and called for a moment of silence because Mickey Mantle had passed away of liver cancer that morning. It was an extremely emotional moment for Mark to be standing at home plate in a major league baseball stadium at this moment. He recalls, “At that time, I was working for Independence Blue Cross in Philadelphia. And…they had a corporate chorus.” The chorus was invited to sing prior to the game. They sang “Lean on Me,” which was the Independence Blue Cross company song, and the National Anthem. He remembers: “Right before [we were to perform] the p.a. announcer came on and said ‘Ladies and Gentlemen, we request a moment of silence for one of the baseball heroes of our lifetime passed away this morning, Mickey [Mark starts to cry as he continues] Mantle of the Yankees. And, I had known that he had passed that morning, I didn’t think much of it, and then it hit me like a thunderbolt when I was standing at home plate as there were thousands of people in a moment of silence for my boyhood hero.”

Mark composes himself and says, “And then after everyone started to applaud, we broke into song, and [the Phillies’ mascot] the Phanatic started to mess with one of the members of the chorus who was standing on the end—and that was I—and he kept banging me on the butt with a tambourine…just trying to disrupt my singing and so on, so, it turned from ultimate sadness to a real big laugh. But that was a moment that I will never forget. To be at home plate, any stadium, in honor of The Mick. Yeah, that was something special.”

FINLAND

Mark was in an accelerated program in school and thus was able to enroll in Michigan State University at the tender age of 16. Upon reflection, Mark says this was a bad idea, and he cautions against pushing kids academically too quickly, today. He says that at sixteen he was far from ready to deal with university studies and enrolled in classes in disciplines he did not even understand, such as political science. After being cast adrift for years, he eventually left the university without taking a degree. For someone who does not like to dwell in regrets, it is something when he says this was one of the biggest regrets of his life.

Back in New York, Mark took a job at IBM. The counterculture of the late 1960s spoke more to Mark than the 9-to-5 routine. He and a friend decided they were going to see the world, and they started taking extra time off whenever they could get it and vacationed throughout Europe. Then, as luck would have it, Mark found himself on the island of Palma de Mallorca in July 1970. Deciding he needed a new t-shirt and a pair of shorts, Mark wandered into a boutique. There he found the t-shirt, the pair of shorts, and so much more.

Aila Korhonen had left Finland looking for the adventure that her factory hometown of Varkaus had not provided. She went to Palma de Mallorca and took a job in the boutique in which Mark sought his new attire. Mark proceeded to return to the boutique every day for the rest of his trip. He talked to Aila and even composed poetry and recited it to her. And every day he asked her out. And every day she declined. She explained that she had moved to the island and did not want to get involved with tourists. But on the last day of his trip, Aila relented. She agreed to meet Mark that evening in a discotheque café called Crazy Daisies. There Mark went and waited. And waited. And waited. Then Aila showed up at the discotheque with friends three hours late. She claimed she had forgotten. The next day Mark missed his plane. There was no reason for him to miss his plane; he just missed it. Of course, he went back to the boutique. When Aila saw him, she exclaimed, “You liar! You schemer!” But Mark protested. There really had been a plane, and he really had missed it. Eventually, Mark convinced Aila to go out with him again that night. She agreed, and that night they became closer. He then returned to New York. But he could not stop thinking about Aila. He decided to quit his job at IBM, cash in his stock options, and buy another plane ticket to Palma de Mallorca. When he told his father, Marvin thought his son had gone mad. “What happened to your Yiddische Kop? My son has a Goyische Kop!” But whatever Kop or head Mark had, it—or rather his Harts (heart)—was telling him one thing, and one thing only: He had to return to Palma de Mallorca. He would spend his time writing poems. He returned to the island and went directly to the boutique. As he turned the corner, he saw Aila sitting on a stool. As he started to approach her, she caught sight of him and fell off the stool. Mark said he had promised to come back, and he was back. That was October 1970. In December, Mark and Aila stood before the mayor of Varkaus, Finland, and were married.

Mark says he remembers that when Aila left her mother in Finland after Mark and Aila got married, mother and daughter did not hug. Mark thought that particularly odd. But it was then that he started to gain some insight into the Finnish character. He says that when they met, Aila very much embodied the Finnish character of being reserved, stoic, taught to do hard work and not express emotions. But like Mark, Aila had Wanderlust, and that is why she wound up in Palma de Mallorca and the boutique where Mark had sought a t-shirt and a pair of shorts. Perhaps her Wanderlust had been planted early by her grandmother who talked often about how her own sister had gone off to America and who had surmised that America must be such a wonderful place. And thus, perhaps Mark had just been at the right place at the right time: He was an American who had come up to her in Palma de Mallorca and who wanted to take her to America with him,

I think that she jumped at that opportunity as the next step in her adventure. I don’t know how much of it was because she loved me, or how much she was just continuing her adventures. But, we rubbed off on each other a lot. And so, I believe that her personality changed once she became a New Yorker, and once she saw the warmth of my parents to me and to her…that changed. I don’t think of her as the stoic Finnish person anymore, especially when she had her own children.

After Mina passed away in 1973, Mark and Aila moved into Marvin’s one-bedroom apartment. Along with leaving Michigan State without a degree, this is one of Mark’s only regrets in life, and it was a big one. He explains that as well-intentioned as the idea was, it turned out not to be a good one, and it put a strain on their young marriage.

They moved in in 1974, and it was the cause of an eventual breakup of the marriage in 1977. “Aila moved out to live with a friend, and we were separated.” During this rocky time, Mark took refuge in Brazil. After his mother had passed away, Mark became very close to his Aunt Mina, who eventually passed away in the early 1990s. He says he has travelled to Rio at least ten to fifteen times and says he especially went to visit his aunt after his uncle passed away in 1978.

But Mark explains that he never gave up on Aila. He says, “I’m a not-giver-upper!” and Aila and Mark got back together in 1979. At the time, Marvin was ill, and he passed away within months of Aila’s return to the apartment. In 1982, Aila gave birth to their first daughter, whom Mark says inherited Aila’s personality and Mina’s talent for playing the piano and singing. Mark and Aila moved from the one-room apartment in Manhattan to New Jersey later that year. In 1985, Aila gave birth to their second daughter, whom Mark says inherited Mina’s appearance and soul. The family stayed in New Jersey until Aila saw picturesque Bucks County, Pennsylvania. She told Mark this is where she would like to live, and they moved to Yardley in 1992.

In 2000, the marriage was falling apart again, so Mark and Aila decided to separate. But they continued to maintain their relationship and talk to each other every day until Aila passed away in 2009. Mark explains, “Another unusual, strange relationship…It’s just part of life.” Mark says because he never is one to give up, they “had great years and two great daughters.” He explains, “She was the love of my life, why would I give up?” Mark likes to wear a t-shirt with FINLAND on it. It is clear though, that, for him, the letters of that northern country spell AILA.

Queen Victoria

A guest to Mark’s Yardley condominium cannot help but notice a huge portrait of Queen Victoria in the guest bedroom. It is perhaps four feet by three feet—thus not too far from life-size! Moreover, there is a circle cut out around her head as if the head portion could be removed from the portrait if so desired. To understand why the portrait hangs on the wall, one needs to go back to the childhood of Mark and Aila’s two daughters.

As Mark and Aila’s girls were growing up, they took various dance and theater courses. In the early 1990s, Mark took some acting classes at Mercer County Community College. He took the courses just for fun with no intention of performing. Meanwhile, Mark’s daughters got involved in more and more theatre productions. After Mark attended one of his daughter’s performances, she said, “Dad, you passed on your love of film and theater and art and all of that, and I’m up here and you’re down there watching me. So, why aren’t you up there?” This was the spark Mark needed. Mark went to the managing director of the theater company the next day and asked if perhaps he could try a small part in a production. Mark explains what happened next: “He cast me in a two-line part in October of 1999, and I’ve been in 126 shows in the theater over the past twenty years, and loving every minute of it, and enjoying some of the greatest roles that a guy could have. As a character actor. I was too old to get the girl, which was the sad part. I always wanted to get the girl, and I’ve only had one stage kiss in all my theater, and it was almost kind of fake, but at least I can count one!”

Mark Newton—or rather, Marco Newton, as he is known on the stage—has played many roles that have connected deeply with him over the years. He remembers his role in The Investigation, where Mark played the judge at the Nuremberg Trials: “The atrocities described in there were beyond belief, and every night I had to sit and listen to them.” He played a psychiatrist in the play 2, which was about Hermann Goering in captivity. Mark played the American psychiatrist assigned to interact with Goering. He played a Jewish man who was trying to increase his insurance policy in The Interview. He also played Herr Schultz in Cabaret: “Another little old Jewish man…[Mark feigns anger] Wait a minute! Am I going to be typecast as a little old Jewish man?—I don’t even look like a little old Jewish man! [Mark feigns resignation] Wait a minute, maybe I do!” Mark revels as he thinks of Herr Schulz:

That was a delicious role because I got to sing a song called Mieskeit. Mieskeit is a Yiddish word that they say about unattractive women. So, a guy says, “I’ve got a girl for you.” Somebody interrupts and says “Don’t go, she’s a Mieskeit!” And so, in that play—musical—they wrote a song called Mieskeit, and I was explaining to the people on stage and the audience what is a Mieskeit. And that is probably my most memorable time on stage, where I had total command of the actors on stage and the full attention of the audience.

Mark, like his mother before him, likes to make people laugh. Mieskeit brought out the laughter, but the biggest laugh came out of Queen Victoria:

There was a play called Something’s Afoot. Something’s Afoot is kind of a musical version of [Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None]. Different characters but similar theme that each character dies out under strange circumstances. My character was the gardener or the lawnkeeper, and my death was due to an explosion in a stove, but we did not show it on stage. We staged the explosion backstage, and so, in order to show how this man died, my head would come through the wall, and just, like, as a result of a big explosion. And on the wall was this big portrait of Queen Victoria as a piece of art. And, we cut out the head—it was cardboard—we cut out the head, and I stood on a ladder backstage and as soon as the explosion sound came, I pushed my head through this little opening of the cutout, and instead of Queen Victoria’s head on her body it was my head of the exploded [he chuckles] groundskeeper. And that got one of the biggest laughs the stage had ever had!

Mark says that he has played some wonderful roles over the years. But he points out that there is something more important than the actual acting:

More than the acting and everything is the camaraderie and the company of actors. Somebody says, ‘Why are actors always patting themselves on the back, “Oh great show” and so on and “It’s just wonderful” and so on. I say, “Haven’t you figured it out?” If you’re involved in an activity that requires you to expel these deep emotions that are inside of you in public on stage to other strangers, how can you not become close to them? You share in that experience. I always remember that, and that was true. And I still have deep friendships and memories to this day [from] all of those shows that I did. And…I don’t think I would have had the life I had without that. So, coming from the Hebrew school shows, when I was thirteen, and singing with my mother, and so on, all comes to fruition in the most unexpected way and the most unexpected place. New York City boy from Harlem makes good in Yardley, Pennsylvania. Where do you get that headline?

Thinking back on the 126 productions in which he participated, Mark says, “Theatre has brought me life. But based on what I’ve told you guys, everything has brought me life! I’m rejoicing it as I’m speaking with you.”

Cinema Paradiso

Mark Newton sends guests home with an important assignment: They must watch the film that is to be found all over Mark’s condominium in one form or another, whether it be poster, bedspread, or pillow: Cinema Paradiso. The film brings home the importance of splicing together beautiful moments of life and love.

When spliced together or “intertwined,” the odds and ends that adorn Mark’s condominium and the stories he tells convey a message of humor and love; collectively they are a testament to the life Mietek Nowomiast from Warsaw and Mina Kaplan from Pinsk provided for him. He says, “I guess ‘intertwine’ is the operative word we can use for all the stories I have told you and the ones you’ve pried open from me. ‘Intertwine’ is what it’s all about. Talk about starting in Shanghai, you wind up in Brazil and Manhattan and in Yardley-fucking-Pennsylvania! It’s all humorous and it all comes together in some way!”

Humor is a vessel of many emotions. As Mark points out, for example, “Your Mama” can be both an epithet and a humorous greeting. Humor is often a conscious or unconscious way to confront sadness with optimism. Both Mietek and Mina had their share of sadness. Not all their relatives had been as fortunate as they. According to what his parents told him, Mark believes that his grandfather, Syzja Nowomiast, had already died before the outbreak of the Second World War. His grandmother, Chawa Nowomiast, refused to leave Warsaw with Mietek and Mina and most likely stayed with other family members, such as cousins. Chawa was killed in the Holocaust. Like his brothers Mietek and Stanislaw before him, Maksymilian, had gone to Lithuania seeking escape, but he did not make it any further. Mark says the story he was told was that his Uncle Maksymilian was killed in the streets by the Bolsheviks. Mark thinks Maksimilian was killed long after the other four were already in Shanghai. Maksimilian’s wife, Sylvia, was a psychiatrist who was taken to work for the Nazis. Prior to being taken, she had placed Maksimilian’s and her son in a convent. Sylvia was unable to locate her son after the war and eventually set up a practice in the United States as Sylvia Newtown (she chose Newtown whereas the others went with Newton). Mark says that his memory of his Aunt Sylvia was that “she was a broken woman…because of the loss of her son and what she had to do in the war.” As for his mother’s family, Mark believes they were all killed in the Holocaust.

Despite the sadness and loss of their past, both Mietek and Mina lived their lives in the United States with humor—perhaps Mietek more unconsciously with his natural demeanor and Mina more consciously armed with a good dirty joke. When thinking of the meaning of his parents’ life journey, Mark says,

The first word that comes to mind is “survival.” I believe that especially in America, none of our young people or middle-aged people have any idea of what it’s like to be in a foreign country, survival where you don’t have home, you don’t have the security and support of home. You just have to survive. You don’t have a choice. And we’ve never really been physically attacked or taken over by other forces of other countries. So, we don’t know what it’s like to be under that threat. And if you can go back and on what you’ve learned about China and the Japanese occupation in Shanghai, you learn that these were people who were dominated and had no choice, but the only choice they had was to survive. And that was the daily mission. And most Americans cannot imagine it. So, give tribute to those who survived it and always remember that it could always be you. We don’t expect that in our modern times. But it always could happen. And how would you cope with that? Because we’ve never seen anything on this land like that before ever.

When thinking of his own life journey, love comes into the foreground. Mark found the love of his life unexpectedly and pursued her despite the facts that she initially rejected his advances day after day, the close quarters with Marvin in Manhattan split them temporarily apart in the late 1970s, and they had to live in separate residences during the 2000s. Despite all the ups and downs of the relationship over the years, Mark glows as he remembers the woman he met in a boutique in Palma de Mallorca, wed in a Finnish factory town, and with whom raised two daughters in the United States. Aila was the love of Mark’s life and his daughters, his greatest achievements.

As the bits of film—such as the YOUR MAMA tattoo, the FINLAND t-shirt, the photo of The Mick, and the portrait of Queen Victoria—are spliced into Mark’s Cinema Paradiso montage, Mark’s raison d’être eventually comes clearly into focus. And it turns out it is one that he shares with an angelic soul.

Whereas Mina had interrupted her musical studies when she married Mietek and had other things about which to concern herself in Shanghai, in New York she was eventually able to return to song:

When we moved from Harlem, we moved to the same block where the synagogue and the Hebrew School was. Coincidentally 89th Street West End Avenue. But all that time my mother would take the bus from Harlem to that congregation and she was a member of the choral society of that synagogue. And that way, she found her way back…for her it was also a social thing, she met a lot of the people. She was living in a good neighborhood, and made her life…and she had a chance to sing in public. I have a record of her singing in that choir, and I can still hear her voice out of all of the many. [Mark cries.] So, she came back.

It was Mina—the original Entertainer—who launched Mark on his own path toward bringing laughter and joy to his friends. Mark thinks back: “All the old refugees would gather together—many from Shanghai—in New York. And there would be a party and drinking and eating. And they’d say, ‘Mina, could you play something for us?’ She would play and sing in six different languages. And then, of course, at the end of it, she’d say, ‘And now, my son, Mark, will sing.’ And drag me in there. Part of my early indoctrination into entertaining.” As Mark thinks about his mother entertaining her friends, tears start to well in his eyes: “I was a firm believer in the last few years of searching for my raison d’être. Why am I here? I need to define that. And once I was able to put it into words, my life has been pretty easy, since that point, which was about five, six years ago. And I determined that my raison d’être was to entertain my friends. That’s why I’m here. And then when I just started to say that to you, and I said that about my mother, it makes me quite emotional because that’s exactly what she did. Without even realizing it, that that was her raison d’être.”

For both Mina and Mark Newton, there is nothing better than to entertain one’s friends.

Curtain Call

Mark Newton’s Cinema Paradiso is a life to behold with tears of joy. As the images of the montage appear before him, he says,

This gives me cause to get emotional because we’re talking about things that I haven’t thought of in a long time, and they’re pleasant thoughts. People see me crying and they say “Dad,” “Marco, why are you crying?” And I say, “Tears of joy. Tears of emotion. Tears of joy. I don’t cry out of sadness. This trip is too rich and too beautiful to cry about what didn’t happen. You have to enjoy everything that did happen and be thankful for it…. My girls—my daughters—always say “Daaad!” whenever I break into tears. I say, “Let it be!” “Uh oh! Dad’s crying again! Dad’s crying!” It’s all emotion, and it’s all full of joy. As I said to you earlier, I’ve been a very fortunate man, and I have led an extremely interesting and full life. No complaints. I’m in failing health now, and it kind of scares me, I don’t know if it scares me as much as the disabled Chinese in Shanghai in the streets, but my own mortality is certainly on my mind. Which is why I cherish to say I have everything to be thankful and I’m only optimistic for the future.

The author is grateful to Dean Jon Kilpinen and Prof. Colleen Seguin of Valparaiso University for their support of his research endeavors. He also wishes to thank Dixon W. and Herta E. Benz for their generous support.

[1] The main sources for the article are interviews of Mark Newton conducted in-person by the author on December 29, 2021, in Yardley, PA, and by phone on January 22, 2022. The author conducted follow-up written and verbal correspondence with Mark Newton in order to provide fine-tuning on specific points. Unless otherwise specified in endnotes, the interviews and correspondence serve as the sources for the information provided.

[2] https://personal.math.ubc.ca/~bluman/Sugihara_List_alphabetized_August_27_2021.pdf. (Accessed February 11, 2022.) The Chiune Sugihara Lists website is maintained by George Bluman and is based on the research conducted by Bluman and Akira Kitade.

[3] 19 April 1948 Memorandum, 19 April 1948; “Nowomiast, Mojzcez & Mina” File; N, 1946 – 1951; Classified Visa Files, 1946 – 1951; Record Group 84: Records of the Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State, 1788 – ca. 1991; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. (Note: The files used have been declassified.)

[4] Harry Louis and Bob Currie, The Story of Triumph Motor Cycles (Cambridge: Patrick Stephens Limited, 1978), 11, 66-67.