U.S. Embassy Berlin

The German Model and its Discontents

Ines Wagner

Norwegian Institute for Social Research

Ines Wagner is Research Professor at the Institute for Social Research in Oslo, Norway. Her research focuses on equal pay for work of equal value, the double mobility of capital and labour in the European single market, and technological change and the quality of work. She has held fellowships at the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies at Johns Hopkins in Washington, the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies in Cologne, and the European University Institute in Florence. Professor Wagner has published with, amongst others, Cornell University Press and in popular media outlets such as The Guardian and Harvard Business Review.

Germany and the United States share a legal tradition and constitution that promotes equality for all those living within its borders. However, real world examples show that within these borders some are more equal than others; and certain groups in the labor market profit more from labor market policies than the rest.

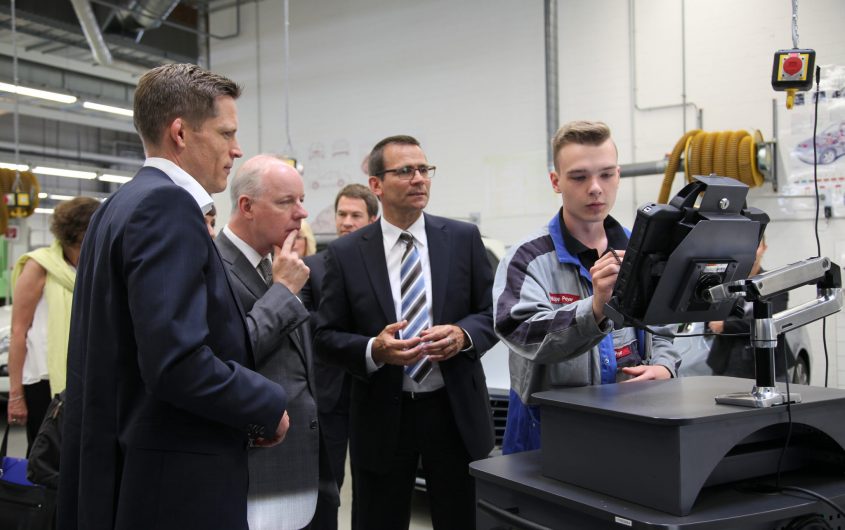

Take the case of vocational education and training (VET) in Germany. The VET program, also known as the dual system, relies on private sector demand, vocational schools, and state subsidies, and has often been taken as the prime example contributing to the strength of the German manufacturing sector. In the discussion of this “German Model” and how it can best be exported to other contexts, such as the U.S. one, we seldom acknowledge that we talk about an ideal “type.” In theory, the VET system profits the whole of the German workforce—but it seldom does so in practice. This has relevance for different groups within the workforce.

In theory, the VET system profits the whole of the German workforce—but it seldom does so in practice.

One discussion is how the VET system relates to refugees and asylum seekers. Here, the aim of the German government is to place refugees and asylum seekers not only into jobs, but also into the VET system. Another topic, which is not as much addressed as the previous one, is the marginalization of intra-EU migrant workers from the VET program. A case in point is EU posted work. More than two million citizens of EU states are posted workers, carrying out their work in another member state while maintaining their employment relationship in their home country. Germany is the largest receiving country of posted work within the EU. Though these workers are performing vital tasks within fields such as construction, nursing, and transport, they are not included in traditional VET programs because the employment relationship is partially regulated from Poland.[1] The issue of being excluded from the dual training system, however, extends beyond the case of posted work. The increasing number of workers in non-standard work arrangements—with a majority being women and migrants—in Germany face similar marginalization from such state-funded training programs. While the German Model with its emphasis on VET programs continuous to function in sectors such as manufacturing, other sectors or population groups within the German workforce show us that this ideal type is at times “exhausted.”[2] Similar trends of labor market dualization are ongoing in the U.S.[3]

The increasing number of workers in non-standard work arrangements—with a majority being women and migrants—in Germany face similar marginalization from such state-funded training programs.

The discussion on workforce cooperation between Germany and the U.S. has to take account of the development of dual labor markets and how skills can be continuously fostered within the new realities of work. The U.S. can look to Germany and the functioning and practice of its VET program. However, Germany can equally learn from the U.S. when it comes to including diverse population groups into an ever evolving and flexible labor market.

[1] Ines Wagner, Workers Without Borders: Posted Work and Precarity in the EU (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2018).

[2] Markus R. Busemeyer and Christine Trampusch, “Liberalization by Exhaustion: Transformative Change in the German Welfare State and Vocational Training System,” Zeitschrift für Sozialreform 59:3 (2013): 291–312.

[3] Louis Hyman, Temp: How American Work, American Business, and the American Dream Became Temporary (New York: Viking, 2017).