Populism: Signals and Noises

Jackson Janes

President Emeritus of AGI

Jackson Janes is the President Emeritus of the American-German Institute at the Johns Hopkins University in Washington, DC, where he has been affiliated since 1989.

Dr. Janes has been engaged in German-American affairs in numerous capacities over many years. He has studied and taught in German universities in Freiburg, Giessen and Tübingen. He was the Director of the German-American Institute in Tübingen (1977-1980) and then directed the European office of The German Marshall Fund of the United States in Bonn (1980-1985). Before joining AICGS, he served as Director of Program Development at the University Center for International Studies at the University of Pittsburgh (1986-1988). He was also Chair of the German Speaking Areas in Europe Program at the Foreign Service Institute in Washington, DC, from 1999-2000 and is Honorary President of the International Association for the Study of German Politics .

Dr. Janes is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, the International Institute for Strategic Studies, the Atlantic Council of the United States, and American Purpose. He serves on the advisory boards of the Berlin office of the American Jewish Committee, and the Beirat der Zeitschrift für Außen- und Sicherheitspolitik (ZfAS). He serves on the Selection Committee for the Bundeskanzler Fellowships for the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

Dr. Janes has lectured throughout Europe and the United States and has published extensively on issues dealing with Germany, German-American relations, and transatlantic affairs. In addition to regular commentary given to European and American news radio, he has appeared on CBS, CNN, C-SPAN, PBS, CBC, and is a frequent commentator on German television. Dr. Janes is listed in Who’s Who in America and Who’s Who in Education.

In 2005, Dr. Janes was awarded the Officer’s Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, Germany’s highest civilian award.

Education:

Ph.D., International Relations, Claremont Graduate School, Claremont, California

M.A., Divinity School, University of Chicago

B.A., Sociology, Colgate University

Expertise:

Transatlantic relations, German-American relations, domestic German politics, German-EU relations, transatlantic affairs.

__

Yogi Berra once said that it’s very difficult to predict anything—especially the future. But when you are trying to face that task the biggest challenge is to ask the right questions.

Populism is a combination of both signals and noise, but detecting its meaning and impact is a difficult challenge. Differentiating between the noise of populist movements in politics and the signals they project about the political environment requires, as Nate Silver has argued, getting comfortable with uncertainty.

The usual rationale of populist movements within political systems is to challenge the status quo. But in most cases the purpose of populist leaders is to secure for themselves the same power they criticize in the hands of others. The noises and signals circling around populist movements mobilizes people, with mixed results, impact, and staying power. In the current environment on both sides of the Atlantic, there is no doubt that a populist wave and mood is emerging.

But what triggers set that wave in motion? What are the signals we need to notice? Even prior to those questions we might ask: what is populism? Is it a generic phenomenon similar on either side of the Atlantic? Or is it framed differently in each country in which it appears?

Since populism derives from the Latin populus, there has always been a nagging set of questions lurking: who are the people? Which are “the people” and which are not “the people”? Who claims to speak on behalf of the people? With what authority?

A quick review of how the word “people” as it appears in various political declarations shows the range of its use for different purposes and in different frameworks. Abraham Lincoln used it in the middle of the American Civil War, saying “Government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.” One has to wonder to whom he was addressing his remarks at a time when consensus—even over a single word—was nearly impossible to achieve.

Over the last two centuries the word “people” appears in any number of political testimonies framing the government of countries. Five examples:

- “We the People of the United States, in order to form a more perfect Union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

- “Inspired by the will to promote world peace as an equitable member in a united Europe, the German people, in the exercise of their constitutional power, have adopted this Basic Law.

- “The principle of the Republic shall be: government of the people, by the people and for the people. National sovereignty shall vest in the people, who shall exercise it through their representatives and by means of referendum.

- “The bearer of sovereignty and the only source of power in the Russian Federation shall be its multinational people. […] The federal structure of the Russian Federation is based on […] the equality and self-determination of peoples in the Russian Federation.”

- “The People’s Republic of China is a socialist state under the people’s democratic dictatorship led by the working class and based on the alliance of workers and peasants. […] Disruption of the socialist system by any organization or individual is prohibited.”

In each case the word “people” is taken as a sacred reference point—even though the application of what goes with it is different in each case, depending on and shaped by the history and the power structures of those writing the words at the time.

Political populism is said to be a shadow on democracies—something that can be portrayed as a threat or as therapy. It has the characteristics of a symptom and a cause. Whether it is seen as a positive or a negative factor is in the eye of the beholder. Because at its root, populism is about power.

If we read the following words, we find them echoed through the past centuries or even in the current atmosphere of the transatlantic community:

“The conditions which surround us best justify our co-operation; we meet in the midst of a nation brought to the verge of moral, political, and material ruin. Corruption dominates the ballot-box, the Legislatures, the Congress, and touches even the ermine of the bench. The people are demoralized; most of the States have been compelled to isolate the voters at the polling places to prevent universal intimidation and bribery. The newspapers are largely subsidized or muzzled, public opinion silenced, business prostrated, homes covered with mortgages, labor impoverished, and the land concentrating in the hands of capitalists. The urban workmen are denied the right to organize for self-protection, imported pauperized labor beats down their wages, a hireling standing army, unrecognized by our laws, is established to shoot them down. The fruits of the toil of millions are boldly stolen to build up colossal fortunes for a few, unprecedented in the history of mankind; and the possessors of those, in turn, despise the republic and endanger liberty. From the same prolific womb of governmental injustice we breed the two great classes—tramps and millionaires.”

That statement is part of the platform of the Populist Party of the U.S. in 1893. Yet we hear echoes of a good part in the inaugural address of the current U.S. president or in the platforms of many political movements in Europe today. There are even echoes throughout the world in South America, in protests in Russia and Turkey, and a few years ago in the period we called the Arab Spring.

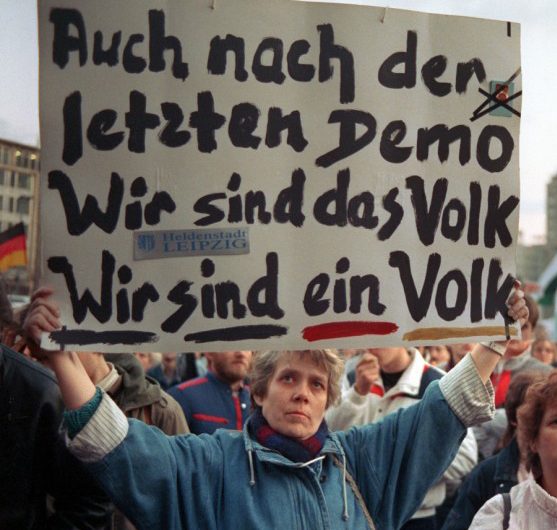

Further back, another example might have been seen in the streets of Dresden and elsewhere in East Germany in 1989. As marchers carried around with them banners that said “we are the people,” the slogan eventually evolved into “we are one people” as the momentum for German unification picked up speed.

But then again, who are the people doing the protesting? Against which people? And for what purpose?

Bertold Brecht once asked an important question in this context: “All power comes from the people…But where does it go?”

The institutionalized narratives of many nations talk of “the people” and indeed inscribe into their most sacred documents the word “people.” But within these frameworks there may be a constant dynamic asking the same question: “who are the people?” It is interesting to note that in the Russian Federation context, the reference is to “peoples.” And when we refer to people, is it not always in the plural? Is there ever really one people—in any political system?

In looking at the current expressions of political populism in Europe and the United States, there are several common traits visible even if they are framed within different historical narratives and used by those either seeking power or by those who already wield it.

There is a desire to understand the world as made of authentic or “real” people with authentic interests and led by authentic leaders. These “real” people are threatened by those who are marginal or hostile. They are led by those who execute the real people’s will…unless it may be somehow undermined by betrayal. Populists are never in want of enemies or conspiracies.

Many of those “enemies” are found in the form of the media, in non-governmental organizations, or in other political parties. When a populist movement can achieve political control of a country, steps can be taken to crack down on or even eliminate those threats. One might think of current developments in Turkey, Russia, Egypt, Hungary, or the Philippines.

The slogan from many populist movements is always connected with the demand that they want to take back their country. But from whom they want to take it back can vary depending on who is in power.

In the United States, think of Donald Trump’s inaugural speech: “January 20, 2017, will be remembered as the day the people became the rulers of this nation again.”

In Europe, here is Geert Wilders in the Netherlands: “I am not comparing myself with Donald Trump but the people are fed up with politicians ignoring the problem.” Or, here, Marine Le Pen: “I defend French people. […] I defend the interests of France, the interests of French people.” There’s also Hungary’s Viktor Orban: “We don’t go against the will of the people. […] We would like to preserve Europe for Europeans—what sort of Europe do we want to have? Muslim communities living together with the Christian community?”

There are many other examples of these populist references to “the people” framed in a national context but with the emphasis on an exclusive claim to its ownership. Today in the European Parliament over 20 percent of the political parties are populist in this sense, whether they be found on the far right or the far left.

Donald Trump, Marine Le Pen, and Venezuela’s Nicolas Maduro, among many others, despite vast differences, are all described as populist. They all share similar tactics despite differences in culture, history, and political systems. One common denominator is the “us” versus “them” narrative—“us” being the people represented by the populist leader and “them” being whomever they see as a threat. Populists often draw on feelings of political, social, economic, and racial polarization.

They also focus on depicting threats to the country with the message that the nation is in need of protection and change that only the populist leader can deliver.

Again, Donald Trump’s inaugural address contains many examples of this tactic. His reference to “American carnage,” a faltering economy, or foreign policy crises are illustrative if not unique. Vladimir Putin called the end of the Soviet Union “the greatest geopolitical disaster” of the twentieth century. Stating as Donald Trump has done that only he can solve problems and make corrections is a common populist refrain. In Germany, the Alternative for Germany (AfD) got its initial start in exploiting the reaction to Chancellor Merkel’s decision to welcome refugees, which were then depicted as threats to German society. Similar tactics have been deployed by other parties throughout the EU

Once they have assumed power, populists will portray opposition forces not as legitimate citizens, but as threats and conspirators. In many cases where populists have gained power, opposition leaders are jailed or die under mysterious circumstances—Turkey and Russia come to mind. In Turkey, Erdogan was quick to level responsibility for last year’s attempted coup at Fethullah Gülen. He was also quick to accuse the United States of being complicit.

Another shared approach by populist leaders and their followers is to undermine the credibility of both sources of expertise and the media. In a well-known reference in favor of the Brexit campaign last year, a prominent supporter proclaimed “People in this country have had enough of experts,” in reaction to arguments by experts against Brexit. The accusation directed at the media by populists in Germany was framed in a formulation used by the Nazis to attack the press as Lügenpresse (lying press). President Trump’s spokesperson introduced the slogan of “alternative facts” to express disdain for alleged fake news reported by the media.

Regardless of whether people who are avowed populists are in power or are seeking power, these are some of the signals of their intentions:

- There is an emphasis on nationalist identity based on ethnic or racial metrics.

- There is an effort to exploit the weakening of traditional political parties as representing the interests of voters by discrediting traditional political leaders.

- There is also an effort to exploit the fragmentation of the media landscape and the loss of traction and affiliation within societal institutions such as labor unions, religious institutions, or voluntary associations.

- There is the aim of discrediting confidence in government institutions and their leaders.

Surrounding these efforts is the perceived sense of economic anxiety about the future and the desire among voters to seek a clear, simple, and authoritative solution.

The challenge for political leaders who are attempting to counter populist strategies throughout Europe is to address legitimate concerns of those who are feeling threatened within their respective environments, whether it be in terms of societal change, existential threats, or economic uncertainty.

The main signals that can confront populist movements include that which defends the need to include, not exclude, more people in the system of government. It includes a narrative which describes the capacity of a society to absorb diversity under an umbrella of unity (e pluribus unum). Of course, there’s always the question of how much diversity can be tolerated and how much unity can be achieved. But that is the platform on which countries write their history for better or for worse. It may be a noisy argument but it is a worthwhile one.

A version of this essay was delivered as the Keynote Speech at the University of California Berkeley on April 4, 2017.