Elections 2013: Another Merkel Moment?

Jackson Janes

President Emeritus of AGI

Jackson Janes is the President Emeritus of the American-German Institute in Washington, DC, where he has been affiliated since 1989.

Dr. Janes has been engaged in German-American affairs in numerous capacities over many years. He has studied and taught in German universities in Freiburg, Giessen and Tübingen. He was the Director of the German-American Institute in Tübingen (1977-1980) and then directed the European office of The German Marshall Fund of the United States in Bonn (1980-1985). Before joining AICGS, he served as Director of Program Development at the University Center for International Studies at the University of Pittsburgh (1986-1988). He was also Chair of the German Speaking Areas in Europe Program at the Foreign Service Institute in Washington, DC, from 1999-2000 and is Honorary President of the International Association for the Study of German Politics .

Dr. Janes is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, the International Institute for Strategic Studies, the Atlantic Council of the United States, and American Purpose. He serves on the advisory boards of the Berlin office of the American Jewish Committee, and the Beirat der Zeitschrift für Außen- und Sicherheitspolitik (ZfAS). He serves on the Selection Committee for the Bundeskanzler Fellowships for the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

Dr. Janes has lectured throughout Europe and the United States and has published extensively on issues dealing with Germany, German-American relations, and transatlantic affairs. In addition to regular commentary given to European and American news radio, he has appeared on CBS, CNN, C-SPAN, PBS, CBC, and is a frequent commentator on German television. Dr. Janes is listed in Who’s Who in America and Who’s Who in Education.

In 2005, Dr. Janes was awarded the Officer’s Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, Germany’s highest civilian award.

Education:

Ph.D., International Relations, Claremont Graduate School, Claremont, California

M.A., Divinity School, University of Chicago

B.A., Sociology, Colgate University

Expertise:

Transatlantic relations, German-American relations, domestic German politics, German-EU relations, transatlantic affairs.

__

Over the next eight weeks Germans will be thinking about who they prefer to run their government when they vote on 22 September. Most polls today suggest that Angela Merkel will get a third term in office as Chancellor. The remaining question is which partner she will have in a coalition government. Her current partner, the Free Democratic Party (FDP), is currently struggling with its support level and may not generate a majority again with Merkel.

That would leave the option of a coalition with the Social Democrats. Merkel experienced that arrangement in her first term in office (2005-2009), and measured against the fact that she handily won a second term, it was not all that bad for her. Yet there are more than a few Social Democrats who cannot stand the idea of serving as the junior partner in another coalition with Merkel. They are championing a rerun of their coalition with the Greens, but the polling numbers do not point in the direction of a majority—for now. That is very frustrating for many Social Democrats. They look across the country and see that their party governs nine of the sixteen Länder and is in a coalition in thirteen. Why they cannot transform that into a national lead at this point generates much steam within the party.

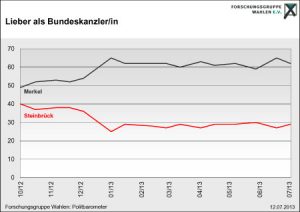

Some blame their lead candidate and challenger to Merkel—Peer Steinbrück—who trails the Chancellor significantly in the polls. The party chose Steinbrück in part because of his effective management of the financial crisis and economic expertise. But no one is talking about the Euro crisis in the German elections and Steinbrück has not been able to make his criticism of Merkel’s management style stick.

Other SPD members are struggling with the party’s recent past. The last Social Democratic chancellor, Gerhard Schroeder, was elected twice, but his legacy has become a problem for the party. In his second term in office, Schroeder managed to push through major economic policy reforms—known as Agenda 2010—which became the basis for Germany’s revitalization after years of stagnation. The agenda involved lowering taxes and making the labor market more flexible, including generating a lower wage job sector. But these reforms are now seen as having exacerbated inequality; the gap between rich and poor Germany has accelerated at a higher pace than most countries in the OECD.

The question for the SPD is whether they can mobilize enough of their voters to get behind Steinbrück over the next eight weeks and lift his momentum. If they are going to win in September, the strength of the SPD at the Länder level will need to be replicated in the national vote. Germans still tend to primarily vote along party lines, but the Chancellor is currently enjoying record levels of personal popularity. How that shakes out in two months remains to be seen. Her sister party in Bavaria, the Christian Social Union, also seems to be gaining momentum—a development that could only help the Chancellor’s reelection chances.

Meanwhile the Free Democrats and the Greens are aiming to mobilize their bases. Announcing projected tax hikes on the rich and new minimum wage policies, the Greens decided to shape their campaign around the equity issue in Germany. Germans generally find taxes less toxic than Americans, but it is nonetheless surprising to see a major party discussing tax hikes during a national election. This is an attempt to tap growing dissatisfaction with the increased concentration of wealth in the upper ten percent, but it is not clear whether this sentiment is enough to shift the vote in favor for the Greens Conversely, the Free Democrats want to energize their base by claiming to maintain lower taxes. They argue that they have fought against tax increases even in the current coalition with Chancellor Merkel. The party is clearly struggling with that campaign, having lost considerable political ground during the past four years.

Part of this decrease has to do with internal squabbling over leadership issues; part of it is due to the problem of articulating a clear message. The FDP got a record result in the 2009 elections following four years of coalition between the two major parties. Germans then were exhausted by “grand coalitions,” but the current CDU-FDP coalition in Berlin has consistently lost ground at the Land level, with the Free Democrats taking a particularly large hit. While the FDP is certain to regain its presence in the Bundestag after September 22, it is not clear as of today whether it can generate enough support to form another majority with Merkel.

What will drive elections over the next two months will primarily revolve around the domestic agenda? The crisis surrounding the euro seems to have receded a bit. There is still blowback among Germans with regard to the economic problems generated in Southern Europe and how much Germany will need to engage in putting out those fires. That can be seen in the emergence of the so-called Alternative for Germany (AfD) which represents that discomfort. But it is not yet evident that the AfD can make a serious dent in the electorate. Mobilization of voters is key for all parties in September, so a few thousand votes here or there can tip the scales in one of the sixteen states. Whether we witness such movement remains to be seen.

The Left Party can rely on core voters primarily in eastern Germany to remain represented in the opposition benches, as no other party will form a coalition with them. There is also the unpredictable Pirate Party, which is currently represented in four state parliaments (Berlin, North Rhine-Westphalia, Saarland, and Schleswig-Holstein), but has been losing momentum at the national level despite the attention given to internet privacy concerns following the NSA revelations.

Two months is a long time in election cycles. A lot can happen between now and September to alter the political landscape. Jokes about the timing of floods impacting German elections emerged following the high waters in June, just as they did in 2002. The uproar over the NSA surveillance issue could continue for a while, but unless a party decides to use it continually over the coming weeks, it will probably fade. The problem for all of the major parties is that the surveillance issue—either American or home-made—will be a part of all of their legacies, for they all have been in government during the last decade. It is not that easy to cast stones when everyone lives in glass houses.

Other issues that may add some spice to the race include rising energy prices, the economic mood closer to mid-September, or maybe even a foreign policy concern or two. But does foreign policy mobilize voters in Germany? The continuing debate over defense issues, such as drones and cost overruns, do not impact too far outside of expert circles, and Germany simply isn’t very involved in out-of-area conflicts, such as those in the Middle East.

If there are no political earthquakes over the next two months, Chancellor Merkel stands a good chance of gaining a third term with the continuation of the current coalition, which she says she wants, or in a new alliance with the Social Democrats, which would make many Germans quite unhappy. Merkel is the first chancellor to have governed in two different political coalitions. That speaks to her skills and her continuing popularity as the pragmatic problem solver.

Four recent books[1] about her suggest that one should not expect a grand vision, but rather watch how she maneuvers and avoids political pitfalls. Regardless of what may come, that approach has given her two election wins so far. The question is what would Chancellor Merkel want to accomplish in a third term? The contours of the coalition she can assemble shapes one part of the answer, and what she anticipates as her legacy shapes another. Still more hangs on events she may not be able to anticipate. Indeed, those three challenges would confront any Chancellor, but less than a decade ago, who might have anticipated that Angela Merkel would be looking at a third run at dealing with them?

Footnotes:

[1]See Stefan Kornelius’ Angela Merkel: Die Kanzelerin und ihre Welt; Alan Crawford and Tony Czuczka’s Angela Merkel: A Chancellorship Forged in Crisis; Judy Dempsey’s Die fruhen Jahren der Angela Merkel, and Gerhard Strohmaier’s Angela Merkel liest Machiavelli