Personal Reconciliation between Germans and Jews

Lily Gardner Feldman

Senior Fellow

Dr. Lily Gardner Feldman is a Senior Fellow at AICGS. She previously served as the Harry & Helen Gray Senior Fellow at AICGS and directed the Institute’s Society, Culture & Politics Program. She has a PhD in Political Science from MIT.

From 1978 until 1991, Dr. Gardner Feldman was a professor of political science (tenured) at Tufts University in Boston. She was also a Research Associate at Harvard University’s Center for European Studies, where she chaired the German Study Group and edited German Politics and Society; and a Research Fellow at Harvard University’s Center for International Affairs, where she chaired the Seminar on the European Community and undertook research in the University Consortium for Research on North America. From 1990 until 1995, Dr. Gardner Feldman was the first Research Director of AICGS and its Co-director in 1995. From 1995 until 1999, she was a Senior Scholar in Residence at the BMW Center for German and European Studies at Georgetown University. She returned to Johns Hopkins University in 1999.

Dr. Gardner Feldman has published widely in the U.S. and Europe on German foreign policy, German-Jewish relations, international reconciliation, non-state entities as foreign policy players, and the EU as an international actor. Her latest publications are: Germany’s Foreign Policy of Reconciliation: From Enmity to Amity, 2014; “Die Bedeutung zivilgesellschaftlicher und staatlicher Institutionen: Zur Vielfalt und Komplexität von Versöhnung,” in Corine Defrance and Ulrich Pfeil, eds., Verständigung und Versöhnung, 2016; and “The Limits and Opportunities of Reconciliation with West Germany During the Cold War: A Comparative Analysis of France, Israel, Poland and Czechoslovakia” in Hideki Kan, ed., The Transformation of the Cold War and the History Problem, 2017 (in Japanese). Her work on Germany’s foreign policy of reconciliation has led to lecture tours in Japan and South Korea.

The Many Levels of Reconciliation

The award of the 2012 Nobel Peace Prize to the European Union has focused attention on how governments in Europe have built lasting reconciliation. Studies of reconciliation have also addressed the critical, catalytic role of societal groups in bringing about and maintaining reconciliation. Much less attention has been paid to how individuals have been engaged in reconciliation, namely how they confront Germany’s past in personal terms. The relationship between Germans and Jews after 1945 reveals a complex process of reconciliation, marked by highly sensitive, yet productive encounters. Just a few days before the 2012 Nobel Peace Prize was announced, one such encounter took place in Waibstadt in southern Germany.

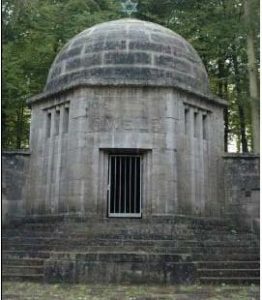

The occasion was the rededication of the Weil mausoleum, 85 years after the mausoleum was erected next to the Jewish cemetery in the Mühlbergwald, where generations of Weil family members had been buried. The mausoleum had been built by Hermann Weil, a Jewish grain merchant and philanthropist, for him and his wife. His son, Felix Weil, financed the founding of the Frankfurt Institute for Social Research (Frankfurter Schule). The mausoleum was desecrated during the 1938 Reichspogromnacht and over many decades fell into complete disrepair. However, in the early 2000s, initiatives on the German and Jewish sides led to the rebuilding of the mausoleum: the school project of the Realschule Waibstadt, devoted to embracing Jewish history in the Kraichgau, and the Weil family reunion in Florida, devoted to reconnection with the family’s German roots.

A variety of individuals – students, teachers, family members – committed themselves to building new relations between Germans and Jews, but two individuals were vital for this remarkable path of personal reconciliation: Marianne Weil Sekulow, the last Weil family member born in Germany (she left Steinsfurt in 1940 at the age of 6); and Siegfried Bastl, a mathematics teacher at the Realschule in Waibstadt, who, together with fellow teachers and students, and in the framework of the Verein Jüdisches Kulturerbe im Kraichgau, raised over 200,000 euros (from federal, state and private sources) for the rebuilding of the mausoleum. Their tireless efforts and creative energy made possible the Weil family reunion of October 2012, when some 30 family members from 6 countries gathered in Waibstadt, Sinsheim, Steinsfurt, Speyer, Neckarzimmern and Neckarbischofsheim for a series of events commemorating Jewish life in this region, with the rededication of the mausoleum serving as the highlight. German schoolchildren were key participants in these events.

The Holocaust Generation’s Commitment to Reconciliation

Marianne Weil Sekulow’s remarks at the civic ceremony in Waibstadt record her personal path from antipathy and concern regarding Germany to friendship and trust:

“I am delighted to be back in Waibstadt once again, to honor the work of Siegi Bastl, and the many individuals and firms that contributed their personal and financial support to restore the Herman Weil Mausoleum. Special thanks go to the Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Land Baden- Wuerttemberg, Stiftung Denkmalschutz Baden-Wurttemberg, Stadt Waibstadt, Firma Benz, Firma Hauk. Firma Lutz, Projekt Judentum im Kraichgau, Juedisches Kulturerbe im Kraichgau e.V. Without your support we would not be standing here today, and I wanted to thank you all.

The Herman Weil Mausoleum is part of the history of the Jewish people who once lived in this proud land. Three years ago we were honored to dedicate the synagogue in Steinsfurt, which not only restored the memory of the Jewish Community in Steinsfurt but brought together members of the Weil Family who once lived here. More importantly, the rededication of the synagogue served as a shining example of the intense desire of the German people to bring truth and reconciliation to the forefront. By confronting its past and not hiding from the truth, Germany has been able build a healthy future and has become the cornerstone of the European Union. Furthermore, Jews from all over the world are choosing to make Germany home. Israel is an educational, technological, and economic partner with Germany, and we, the survivors, are here to confirm our desire to move forward and to continue to build bridges that will unite our children and grandchildren with their German counter-parts and common heritage.

On a more personal note, my journey to this place and time has been an intense emotional roller coaster. 80 years ago, I was born in Mannheim Germany and 80 years ago Adolph Hitler became chancellor of Germany.

From the very beginning of my life, our freedoms were removed year by year. My father’s livelihood was taken away, and I was denied an education; the gravest insult came on November 10, 1938, when my father was arrested and taken to Dachau Concentration Camp. My anger toward Germany was undeniable and it would remain with me for the next 60 years. When I returned to Germany in 1956 as an American tourist, I found a Germany longing for its grand past; Germans still singing Nazi songs, and not acknowledging the awful truth of the Nazi Era. Back in America, German cars, German appliances, German anything was not for my family or for me. We were Americans through and through. And so it went for many years.

However, throughout those years, things that were German seeped back into my life: my love for chocolate covered marzipan; 4711 eau du cologne brought back memories of my grandmother.

Every autumn in time for Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, I baked pflaume Kuchen (also known as schwechekuchen in Steinsfurt). I still yearn for the gooseberries that grew in our garden.I read the stories of Max and Morris and Struwwelpeter to my children. I bounced babies on my knee with Hoppe Hoppe Reider and sang kompt ein fogle gefolgen. All these things were part of me. These memories said “this is home.” It was the comfort food of my younger self that helped to heal the emotional wounds of my experience. These memories lingered and became memories for my children. But I also realized that the dark side of my German past must be recorded for my children and grandchildren, and so a new chapter was opened.

In 1998 I began writing a memoir for my grandchildren. They really didn’t know my history or how the Holocaust had affected our family. To best write down my story, I needed to stir my memory … to see the town, to walk the streets, and to attempt to resolve my inner turmoil. And so, in 2000 my husband and I decided to take what we called our “Jewish trip to Germany.”

Here we found two competing stories. In Steinsfurt we found the former synagogue in a state of total neglect with broken windows, damaged roof, weeds, and a cigarette machine in front of the building. It was designated as a historic building, but it was in shambles and being used as a storage depot. We were very distressed.

But in the big cities, we witnessed interesting changes…. in Berlin a Jewish museum was just opening, and we noted that all Jewish establishments were protected with police guards. In Wannsee we visited a museum that was teaching the awful truth of the Holocaust to foreign students.

In Munich, the police strolled casually around town wearing short jackets with Khaki pants and regular shoes: no black boots, no leather coats, no vicious dogs. This definitely felt like a new Germany.

As a result of that trip to Steinsfurt, the idea of a Weil Family reunion was born and in April of 2002, 75 members of the Steinsfurter Weils gathered in Fort Lauderdale, Florida to reunite and reestablish our common bonds.

To assist us with our memories, a young man named Siegfried Bastl came with pictures of our ancestral homes, and video of Steinsfurt and the surrounding towns.

But Siegi did something else that was life altering: he wanted to record and listen to the stories of those family members who were in Germany and survived the torment of the Nazi Era. He listened, he recorded, he shared our pain, and he became one of the catalysts that would bring Jewish history and Jewish awareness back to Steinsfurt.

He would work to make my fantasy a reality: to reclaim and restore the little synagogue in Steinsfurt as a cultural center.

And today, through the work of an entire community, we gather to rededicate the grand mausoleum to Herman Weil, a great German-Jewish patriot and philanthropist. Prior to his death, Herman dedicated this mausoleum in a ceremony that transferred the care of the atrium of the mausoleum to the city of Waibstadt.

In his remarks, Herman, gave a charge to the mayor that the space be open to all those who love nature and its beauty, that it be open to all societies, that it be open to all groups dedicated to their homeland. He wanted it to be a place of peace and tranquility. I would add that Herman saw this as an opportunity for education and reflection. Today this mausoleum is a living monument not only to Herman, but for this generation of young people to be the guardians and protectors of freedom and tolerance.

We have come a long way together. It is my hope and prayer that as the years progress our bonds will grow even stronger.

In 2009, during our first Weil reunion in Germany, I spoke of the hard work that Germany has done to initiate the process of Teshuva, (the Hebrew word for return & repentance).

Germany has cleaned the deep wounds perpetrated by the Third Reich: it has bared its soul for all to see. And Germany has set a high standard to make history right. We honor you and thank you for making our “homeland” whole again.

I could not have imagined that after fleeing Germany in 1940 under the gravest of circumstances, that 74 years later I would be standing here, in Waibstadt among friends and family and proudly proclaim that I, Marianne Weil, as of the 4th of April 2012, have reclaimed my German Citizenship and am once again a German Citizen. Thank you all for bringing me home again.

The Younger Generation’s Perspective

The remarks of Marianne’s son, Michael Schaffer, at the rededication of the mausoleum, demonstrate the commitment of the next generation of the Weil family to the unbreakable tie between Germans and Jews, and point to the connection between reconciliation and remembrance, between future and past. The Kaddish was recited after his remarks:

“Thank you. I was happy to hear Herr Lutz speak of the stones here. The process of restoration … of supporting the old stones, and putting new stones on top of those old stones … this is an apt metaphor for how the Jewish people have survived for thousands of years. We respect and honor our old foundations, taking care to preserve them and keep them strong. And we add new learning and new thought on top of those foundations as we grow.

On Yom Kippur last week we read from the book of Isaiah, and it seemed entirely appropriate to quote it here (58:12): “And your children will rebuild the old waste places: you shall raise up the foundations of many generations; and you will be called, The Repairer of the Breach, The Restorer of paths to dwell in.”

I wanted to add my personal thanks to the people that made this renovation possible. You have recaptured a piece of history, and pulled it back into the present. You have created a place where I can feel my own family history. And you have created a place for my daughter, and one day, her children … a place they can come and say “this is where I come from”.

These stones – here in the Mausoleum and just over the fence in the Cemetery – these stones have seen a lot. But they have not heard very much in the last seventy years. But for centuries before, our families would bring our dead up to these hills and chant the ancient words of the Kaddish. In this prayer we’re not even speaking Hebrew – this is Aramaic, a language far older than the stones here. This prayer dates from the time of the Second Temple in Jerusalem.

The Kaddish does not mention death or dying: it is a cry of faith and honor: we magnify and sanctify God’s name even in our hour of grief. It’s a prayer of faith and remembrance.

Let us honor and remember our family members buried here, as well as those that perished in the Holocaust all across Europe. Let us remind these old stones of their purpose, in memory and in faith.”

The Ten Principles of Personal Reconciliation

What accounts for this incredible path, starting from different directions, that brought the Weil family and the German participants together? There seem to be 10 principles or requirements of reconciliation, a process that takes time, that is complex, that has its ups and downs, but in the end offers contemporary healing for both victims and perpetrators while constantly remembering and not eclipsing the past. The first six principles relate to both Germans and Jews, the next two to the German participants, and the last two to the Jewish victims.

1. Reconciliation requires courage, the willingness to embark on an unknown journey.

2. Reconciliation requires moral vision, the ability to do what is right, even if it’s unpopular.

3. Reconciliation requires generosity of spirit, the capacity to put oneself in another’s shoes through empathy.

4. Reconciliation requires personal openness, the ability for self-reflection and learning.

5. Reconciliation requires reciprocity, the willingness to build a two-sided relationship, not a one-way street.

6. Reconciliation requires leadership, individuals who are willing to step forward and face the challenges of creating an entirely new relationship.

7. For Germans, reconciliation requires the assumption of responsibility for Germany’s past and the desire to face the truth in all of its horrific detail.

8. For Germans, reconciliation requires perseverance and fortitude to find the many material resources necessary to fulfill the emotional desire for change.

9. For Jews, reconciliation requires neither forgiving nor forgetting. Jews rightly insist that only the murdered victims of the Holocaust or G-d on Yom Kippur can deliver forgiveness. Remembrance is an essential element of Judaism, and memory of the Holocaust and constantly honoring the victims are necessary for personal identity and for the identity of the Jewish people.

10. Finally, as the tenth principle, if not forgiveness, then what gift do Jews bring to Germans in reconciliation? They offer magnanimity, a willingness to respond positively to German overtures and initiatives; a deep commitment to forging a new relationship of cooperation and friendship and trust.

The restored Weil Mausoleum is a symbolic and material confirmation of reconciliation, of both sides coming together to honor the past and the many contributions of Jewish life to German society and to affirm a new beginning between Germans and Jews over the abyss of the Holocaust.

For news reports of the events and slides of schoolchildren’s involvement, see:

“Mausoleum soll Stätte der Begegnung sein”, Rhein-Neckar-Zeitung

“Deutscheland darf wieder Heimat sein”, Rhein-Neckar-Zeitung

“Synagoge wurde zur echten Begegnungsstäatte”, Rhein-Neckar-Zeitung

“Darf man stolz sein, ein Deutscher zu sein?”, Rhein-Neckar-Zeitung